Saturdays are always a busy time for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. But, this past Saturday, the Symphony Center was especially packed for Seong-Jin Cho: winner of the prestigious Chopin Competition in 2015 and one of the world’s most in-demand pianists.

The conductor, Gemma New, walked confidently onto the stage to begin the performance, and the orchestra began Aaron Jay Kernis’ “Musica Celestis.” Written exclusively for the strings, angels singing endless praises of God inspired the piece.

The composer divided the music between several sections, as if ethereal sounds were coming from all around the venue. It started with soft, drawn-out chords imitating a choir. Then, passionate outbursts led to a more tumultuous atmosphere, and the piece descended into chaos. A majestic chord — perhaps a “savior” — brought peace to the piece, which ended just like it started: with utter serenity.

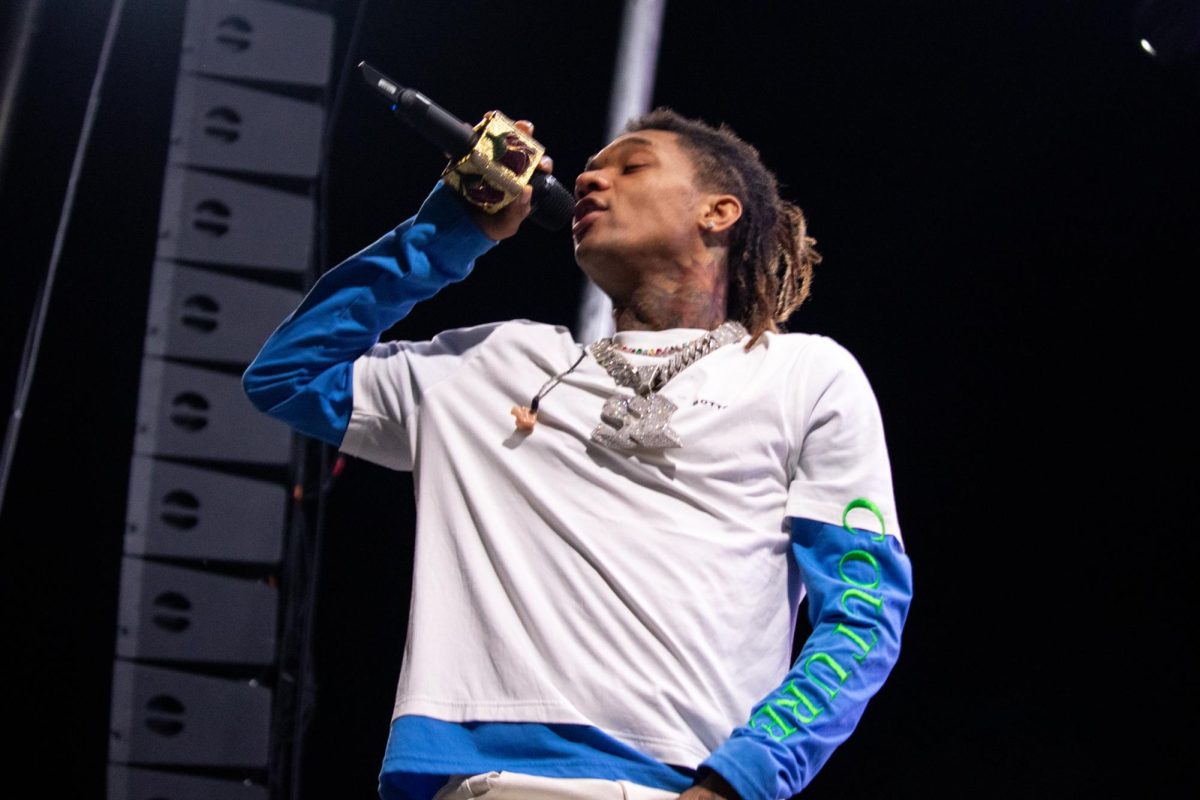

The concert’s highlight was Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Piano Concerto No. 3,” with Cho as the soloist. The audience received Cho very warmly as he walked onstage. He delivered the piece with a performance of consummate power, musicality and technique.

The first movement was somber and resolute, and Cho hit all the right notes (literally and figuratively). Opening in Beethoven’s signature anguished key of C minor, Beethoven unfolded the music in unexpected, daring ways; uncertainty and darkness soon overshadowed fleeting moments of light. The mutual musicianship between Cho, New and the CSO were impeccable; they intently listened to each other and stayed together in difficult passages.

The second movement was full of Cho’s signature lyricism and shimmering orchestral textures. The pulse was at times unsteady — but such mishaps often happen in slow pieces where it is harder to count the beat together.

The third movement, which started without pause, was vintage Beethoven: an exciting tour de force leading to a triumphant ending. Cho kept the atmosphere lively, thoroughly observing Beethoven’s obsessive markings to play loud and accented.

Following the last note of the concerto, the nearly sold-out audience erupted in joyous applause. After a few curtain calls, Cho expressed his gratitude with an encore of the jaunty third movement from Franz Joseph Haydn’s “Sonata in E minor.”

The intermission was followed by Felix Mendelssohn’s “Symphony No. 3,” also known as “Scottish.” The first movement was reminiscent of Beethoven’s music. A hymn-like introduction gave way to dark, tumultuous moments and wild frenzy, after which the hymn came back to conclude the movement. New took a variety of stylistic liberties, slowing down even when there was no marking to do so.

New and the CSO musicians controlled the fleet-footed second movement excellently. A single folk-like tune was tossed around various instruments in creative ways that kept the piece from sounding repetitive. The slow third movement featured a warm melody and romantic dialogue between a solo violinist and a cellist. It was much more in time than the slow movement of the Beethoven concerto.

Where the final movement of Beethoven’s concerto had some sections of calm, Mendelssohn, in the final and fourth movements of his symphony, kept the audience on the edge of their seats. Any semblance of resting space was met with chaos. This back-and-forth created tension, which the CSO handled superbly.

At the height of energy, the orchestra halted. Then, a triumphant final melody declared victory in the musical struggle, and the symphony concluded jubilantly. It was great programming on the orchestra’s part, as the Mendelssohn ended with the same key that the very first piece, Kernis’ “Musica Celestis,” started with: a full-circle ending suiting a wonderful evening of music.

Prior to the concert, the CSO and the Korean-American Association of Chicago hosted a Korean Lunar New Year Celebration. Korean presenters demonstrated traditional Lunar New Year rituals and invited audience members to participate.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is hosting its second College Night of the 2023-24 season on March 21 at 5:30 p.m., alongside a concert featuring Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 4. Tickets for students are $15. Complimentary food will be provided, along with student-geared activities, and a Q&A session with a CSO musician will be held before the concert.

Email: [email protected]

Related Stories:

—From darkness to light: Jaap van Zweden luminously leads the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

—Bienen graduate lands role as associate member of Chicago Symphony Chorus

—A feast of pianistic fantasy: Yulianna Avdeeva enchants with Chopin and Rachmaninoff