When Evanston Township High School student Nancy Cardenas moved up from regular science classes to honors anatomy during her junior year, she went from being part of the non-white majority in the room to just one of a few minority students.

This year, the 12th-grader is the only Latina and one of three minority students in her AP Calculus class of about 20, a familiar yet unsettling setup, she said.

“I felt uncomfortable last year because of the lack of diversity in my class,” said Cardenas, who plans to attend Lake Forest College next year. “That’s a big factor on your education and the relationship you have with the teacher and the students. Seeing people like you gives you hope that you can do it too.”

A research team led by SESP Prof. David Figlio is now studying the curriculum changes ETHS administrators have implemented in the past two years in an effort to address the achievement gap between white and minority students.

Under the new “earned-honors” system, students who scored from average to very high on an eighth-grade achievement exam called EXPLORE are sorted proportionally into freshman year biology and humanities honors classes in which they can only get honors credit if they meet certain academic benchmarks. Students that need remedial help are placed in separate classes, said Peter Bavis, the high school’s assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction.

The new curriculum stoked tensions in the contested Evanston Township High School District 202 school board election earlier this month and remains an issue on which the ETHS community is divided.

Along with Medill Prof. Charles Whitaker, SESP Prof. Thomas Cook, and experts from Harvard University and the American Institutes for Research, Figlio is looking at student achievement measures such as standardized test scores, college enrollment and attendance. Figlio, parent of a freshman and a junior at ETHS, is conducting the study pro bono.

“We’re interested in everything from student aspirations post-high school, survey data, ACT scores to attendance.” he said. “We’re making this as comprehensive as possible.”

The study won’t be complete for another five to six years as the group tracks the high school’s current junior, sophomore and freshman year classes. This year’s sophomore class only participated in the humanities “earned-honors” initiative, though current freshmen are now taking both humanities and biology initiatives under the new structure. The team is using the current junior class as a control group.

The first measures of the initiative’s effect will be available as soon as this fall, after scores for the 10th grade assessment come out for this year’s sophomore class. Whether these results are positive or negative, Figlio said the ETHS community should “hang tight” as more results come in.

Though “detracking” has been attempted in some schools across the country for decades, ETHS is in the minority in terms of its curriculum changes, said Tom Loveless, an education expert at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.

“At the high school level, it’s not very common, so Evanston is unique in trying this in high school,” Loveless said. “Usually it’s tried at the freshman level, usually in English and social studies, but rarely in math and sciences.”

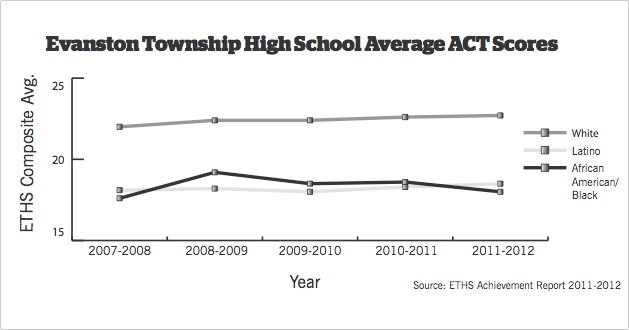

Stark differences in academic achievement compelled the school to change the curriculum, Bavis said. School data for the 2011-12 academic year shows that 11th grade ACT scores for white students averaged 27.6, compared to 19.3 for Latino students and 18 for black students, though all three groups outscored their counterparts throughout the state and nation. Results on other standardized exams show similar disparities.

“The issue is to make AP and honors classes more accessible, specifically to students of color,” said Patricia Savage-Williams, a new school board member. “I don’t think it’s fair that kids, that their whole life plan, is determined by one test, the EXPLORE Test.”

Before the high school implemented the curriculum changes, scores on the EXPLORE test in the eighth grade determined whether ETHS incoming freshmen were placed in honors, regular, or remedial classes. Cardenas scored poorly in the science portion of the exam and for her first two years remained in regular science classes, despite earning all A’s and believing she could have done much more, she said.

“I basically got stuck there in a regular course,” she said. “If they had the mixed classes my freshman year of biology, I would have gotten honors credit.”

As part of the curriculum changes, freshman year humanities class sizes were reduced from about 25 to 20 students, on average, although freshman biology classes have stayed the same size, Bavis said. Additionally, the history department has long offered mixed-level courses except for freshman year, and all electives are mixed-level, he said.

William Farmer, a ninth grade biology teacher and the president of ETHS’ teachers’ council, said his classes are now more representative of the student body than under the previous structure. He said most teachers are in favor of the changes, which he thinks have social benefits and create a more dynamic learning atmosphere.

“In general we appreciate the structure of the classes,” he said. “We think it’s been more thoughtfully developed than what existed before.”

Parents have expressed strong feelings about the changes. A mother, who asked not to be named because she has a freshman and a junior at the school, said she thought the “earned-honors” classes her son is currently taking are not as rigorous as the same classes her daughter took as a freshman.

“I don’t care who’s in the classroom with my kids,” she said. “What I care about is that they’re challenged and that there’s integrity to what they’re calling these classes.”

ETHS parent Elliot Frolichstein-Appel said he supports the curriculum changes but wants the school to act according to the results of Figlio’s study.

“The jury is still out on this one,” Frolichstein-Appel said. “But it’s better than one test they took on a Saturday in the eighth grade.”

Experts disagree on the merits of the tracking system. Loveless said the “detracking” initiatives he’s studied in the past were largely unsuccessful, although ETHS’ is different. Figlio said he hopes administrators will tinker with the initiatives as measures of the system’s success gradually come in rather than waiting until the study is complete.

“I personally would be surprised if the whole initiative turned out to be negative,” Figlio said. “I don’t think this is a disaster. There’s a lot of ground between not a disaster and great success. And it’s going to be somewhere in that continuum.”