Content warning: This article contains discussion of abuse, sexual assault, eating disorders and racism.

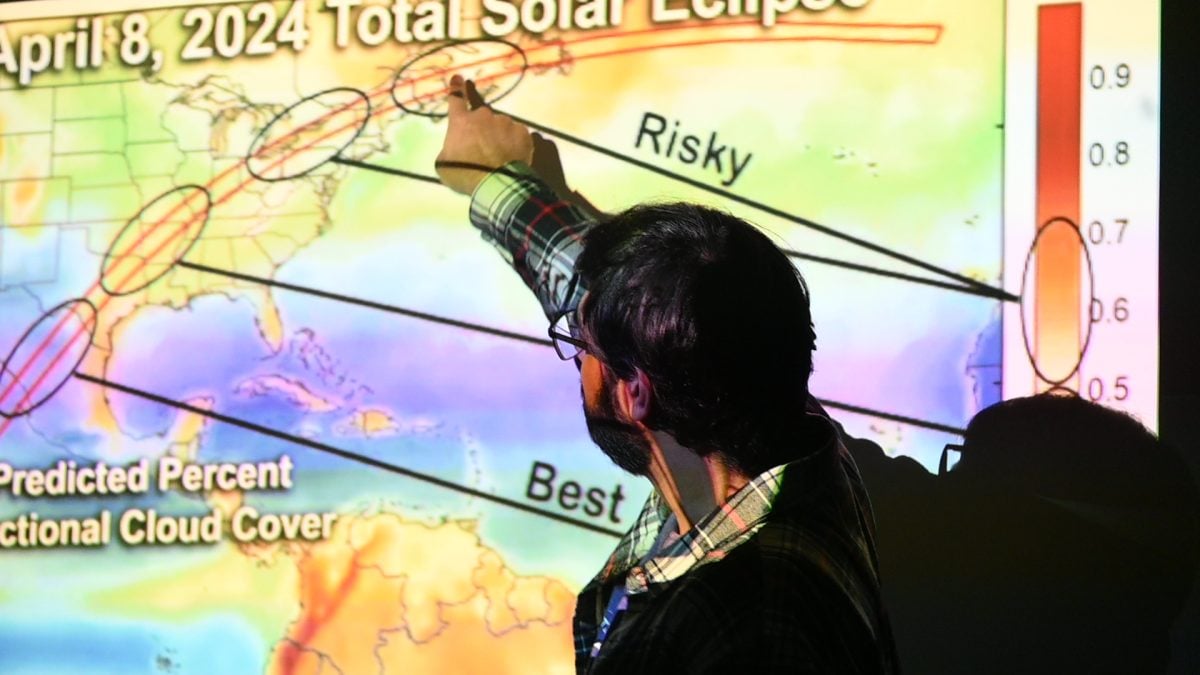

After Northwestern University President Michael Schill reviewed testimony in July from football players alleging hazing and sexual misconduct in NU’s football program, he suspended former head football coach Pat Fitzgerald for two weeks.

But when details of the allegations became public, the president reversed course, announcing he had “erred” in his decision. Two days later, Schill told the University community he’d decided to “relieve Fitzgerald of his duties” — effective immediately.

Schill has been scrutinized by some for his quick change of heart, and players involved in the investigation told The Daily their experience with Schill was frustrating.

Still, doling out punishment only after public scrutiny is nothing new for Schill, former students, reporters and athletes told The Daily. It’s something that marked his tenure at the University of Oregon.

Former UO professor Cheyney Ryan said he noticed parallels between Schill’s leadership at UO and his handling of hazing in NU’s football program.

“I think that there is a general culture of indifference,” Ryan said. “The difficulty is, as long as the solutions are coming out of the president’s office, things don’t substantially change. And I think it’s very sad.”

Throughout his time as UO president, Schill weathered several athletics controversies. Some students say they still have questions about the way Schill handled complaints of abusive drills on Oregon’s football team, eating disorders on the track team and sexual assault allegations on the basketball team.

Multiple inconclusive investigations at NU

A former NU football player, who requested to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, told The Daily in July he was disappointed with the University’s initial “blanket statement” about Fitzgerald’s suspension.

The former player was the first to report the hazing incidents. He said he was upset that Schill and other administrators did not provide a statement of action alongside Fitzgerald’s suspension. He felt Fitzgerald’s suspension was inadequate, noting it took place during a dead period for football, a time when the NCAA bars coaches from recruiting.

“I think that anyone who hears this can agree that these actions are definitely not actions that ‘fine young men’ benefiting the program and the University’s character would engage in,” the player said in July, referring to Fitzgerald’s note after his initial suspension. “It’s stuff that is not going to change through a two-week slap on the wrist.”

Fitzgerald’s lawyer didn’t respond to The Daily’s request for comment.

Schill told The Daily in a statement he is responsive to concerns from student athletes.

“I met with members of the football team right after Coach Pat Fitzgerald was terminated and I maintain an open-door policy,” Schill said in the statement. “Since that time, I have met with (current head football) coach (David) Braun on several occasions to check in, to discuss the team and their concerns, and I will continue to do so moving forward.”

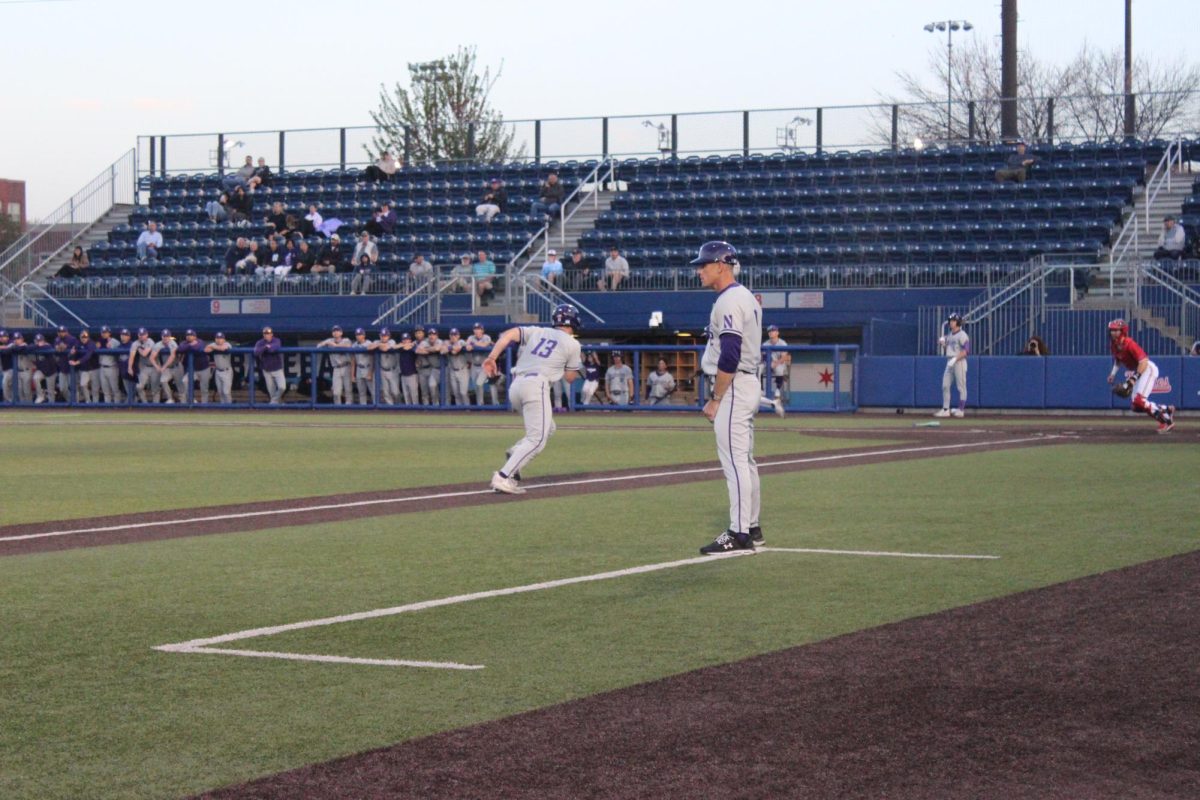

Just days after Fitzgerald was terminated, allegations by players and coaches in NU’s baseball program against former head baseball coach Jim Foster became public. Foster, who had only been at NU for one year, was relieved of his duties after nine players and team staffers came forward and told their story to Chicago radio station 670 The Score.

Foster was NU’s fourth head baseball coach in four years.

Coaches involved in NU’s baseball program first submitted an HR report about Foster last November during Schill’s first quarter at NU, a source familiar with the situation told The Daily. The report alleged Foster engaged in bullying and abusive behavior, spoke inappropriately to a female staff member and made racist remarks to others.

“We’ve been trying to get this out through the proper channels our entire career,” the source said. “We went to human resources, which is the way we thought it should be done … That warranted zero ramifications.”

The University’s investigation did not find Foster responsible for all of the allegations in the HR report, the source said. 15 players entered the transfer portal seeking to leave NU’s baseball team during the 2022-23 season.

Pitching coach Jon Strauss, hitting coach and Recruiting Coordinator Dusty Napoleon and Director of Operations Chris Beacom all stepped away from the program during Foster’s yearlong tenure.

Foster’s lawyer, James Kelly, said the allegations are unfounded.

“Coach Foster denies all allegations of wrongdoing,” he wrote in a statement to The Daily. “He looks forward to vigorously defending these false claims.”

A 2017 investigation into UO football

Before coming to NU, Schill served as president of the University of Oregon from 2015 to 2022. There, his administration also evaluated several reports and complaints about the school’s football program.

In 2019, two football players sued UO, former head coach Willie Taggart, former strength coach Irele Oderinde and the NCAA for alleged abusive offseason workouts.

In these lawsuits, players alleged they sustained significant and permanent physical injuries caused by workouts in 2017. Both plaintiffs — along with another player — were hospitalized and developed rhabdomyolysis, which causes muscle tissue to disintegrate and leak into the bloodstream.

One of the students represented in the lawsuit was former offensive lineman Doug Brenner. Greg Kafoury, Brenner’s attorney, told The Daily the injuries severely altered Brenner’s life.

“He was facing long term kidney damage, which can lead to shortened life expectancy, need for dialysis, need for kidney transplants — it’s grim business,” Kafoury said.

Brenner’s kidney doctor, Raymond Petrillo, testified during the trial in April 2022 that Brenner’s life span was shortened by 10 to 15 years.

The Daily asked Schill in July about the nature of these workouts at UO. Schill said Oregon could get “quite hot” during the summer, and the practices left players dehydrated.

“Let me clarify,” Schill said in a November statement to The Daily. “The dehydration suffered by the student-athletes was not caused by the heat. It was caused by the excessive physical exertion by student-athletes during training sessions with a new coaching staff.”

The lawsuit alleges UO coaches forced football players to do “perfect” push-ups in unison — and added on more when the players failed. It also alleges coaches did not make water available to the players for at least the first day of practices.

“During the workout, if even one student athlete needed to stop performing the punishment drills to catch his breath, to vomit, or otherwise address physical pain or injury, then the rest of the student athletes were punished with additional push-ups or up-downs until the exhausted, injured or vomiting student athlete returned,” the lawsuit stated.

After an institutional review, the university, under Schill’s leadership, suspended one of the coaches for four weeks without pay. Neither coach involved was fired. Attempts by The Daily to reach the coaches were not successful.

A former reporter for UO’s student newspaper The Daily Emerald, who wished to remain anonymous at the request of his current employer, was involved in covering the lawsuits. He feels Schill minimized the events of the case and other sports-related lawsuits.

“I would say at large it seemed that he didn’t take complaints like that seriously until it seemed like the University would get sued,” the former reporter wrote in a statement to The Daily. “He very rarely talked to our reporters.”

Schill said in July his handling of this case at UO was “totally dissimilar” to his process reviewing hazing allegations at NU. When the three UO players were hospitalized, he said his decision to institute a four-week suspension was informed by the university’s investigation.

“I think that the penalty for him was the appropriate penalty,” Schill said in July. “The facts and circumstances of each case are different, and I am happy to say that what we did sent a message.”

According to Kafoury, Brenner reached a legal settlement with UO two years after filing the lawsuit. The other player, Sam Poutasi, also settled. By then, both coaches had left the school of their own volition. Schill was still president of the University.

“At the trial, the UO lawyers admitted these drills should not have taken place,” Kafoury said.

“Coach Oderinde failed to protect the health and welfare of the UO student-athletes,” Schill said in a November statement to The Daily in which he acknowledged the players developed rhabdomyolysis.

Questions over response to sexual assault allegations

Research has shown that college-age adults across the United States are at high risk for sexual violence. Since entering college, 22% of students reported experiencing at least one incident of sexual assault, according to a 2017 study by PLOS One. Women and gender nonconforming students reported the highest rates of assault.

This trend is not specific to UO or NU. But, under Schill’s leadership, athletes accused of sexual assault have been allowed to continue participating in athletics.

In August, a former NU lacrosse player filed an anonymous lawsuit against NU, alleging the school did not adequately respond after she was assaulted by a baseball player in July 2022.

The lawsuit says seven current and former classmates of baseball player Chad Readey warned NU officials — including former President Morton Schapiro and former head baseball coach Spencer Allen — in 2020 that Readey “had a documented history as a serial, sexual abuser toward his female classmates throughout middle and high school.”

The lawsuit alleges the plaintiff complained to both NU Athletic Director Derrick Gragg and Northwestern’s Title IX office in January and February 2023, during Schill’s tenure, saying she was a “direct victim of Chad Readey’s disgusting behavior.”

According to the lawsuit, Gragg did not respond to the plaintiff’s email for sixteen days, and no further action was taken. Readey still plays on NU’s baseball team.

Gragg did not see the initial email and apologized for his lack of immediate communication, Schill told The Daily on his behalf. Schill added he cannot comment on active litigation.

The University said in an October court filing that both parties have agreed to engage in settlement discussions for the lawsuit, which may take several months. Readey has also filed a lawsuit against Tamara Holder, the original complainant’s lawyer, denying the lacrosse player’s allegations.

Readey’s lawyer, Andrew Miltenberg, said in a statement to The Daily the accusations are false.

“This lawsuit is an unscrupulous attempt to smear our client and subvert a campus investigation through the Northwestern Office of Civil Rights, as well as an effort to deflect from the fact that our client has his own claims of suffered abuse that the University is reviewing,” Miltenberg wrote.

Meanwhile, The Daily Emerald found in 2017, during Schill’s tenure, UO allowed basketball player Kavell Bigby-Williams to play 37 games while under criminal investigation for sexual assault.

Bigby-Williams arrived at UO in 2016 after transferring from Gillette College in Wyoming. On the third day of the fall term, University of Oregon Police detective Kathy Flynn received a phone call from Northern Wyoming Community College District police, according to a police report obtained by The Daily.

Detectives in Wyoming called for assistance in interviewing Bigby-Williams in their investigation of an alleged sexual assault. Flynn called Bigby-Williams twice before telling Oregon’s Title IX coordinator and a deputy athletic director about the investigation into Bigby-Williams, records show.

After failing to reach Bigby-Williams, UO officials did not follow university protocol requiring the Title IX coordinator to notify the school’s director of student conduct and community standards after being informed of a Title IX violation. Detectives had made it clear that Bigby-Williams was being investigated in a sexual assault case.

Still, the Title IX coordinator did not inform the director of student conduct and community standards.

At UO, it is the director’s job to determine what steps should be taken to protect students. The director of student conduct could have determined sanctions on Bigby-Williams while he remained under formal investigation.

Instead, Bigby-Williams stayed on the basketball team for the remainder of the season, playing until the team’s 2017 loss in the Final Four. His agent did not return a request for comment. Bigby-Williams was never charged with any crimes.

Then-student journalist Kenny Jacoby broke the story about Bigby-Williams’ investigation in the Daily Emerald. He later wrote in Sports Illustrated that he repeatedly pressed Schill about what he and the administration knew.

According to Jacoby, Schill was less than responsive to his questions.

“I don’t have any awareness of that,” Jacoby quoted Schill saying in a 2017 piece for Sports Illustrated. “In any event, I can’t comment on an individual student. What if I was asked by another reporter about you being obnoxious? Would you want me to tell them that?”

Meanwhile, UO’s administration maintained their stance that the Title IX coordinator and deputy coordinator, as well as the athletic director, followed all University policies, given the investigation wasn’t being conducted by UO.

Schill told The Daily in a statement he does not have involvement in Title IX investigations at NU and did not at UO.

“I was not privy to the process at the time,” Schill said in the statement. “(I) supported the competence and good work of the Title IX officer at that time. I was advised that the Title IX Office determined there was no ongoing risk to campus health and safety.”

According to documents obtained by The Daily, evidence was gathered by the time UO’s detective approached the school’s Title IX coordinator. The Gillette detective took photos of bruising on a woman’s neck, collected her clothes and sheets and documented interviews with her roommates, who said they saw her unconscious prior to the incident.

The Gillette detective also informed UO police of the investigation just 11 days after the alleged incident occurred, according to the police report obtained by The Daily. Still, UO’s Title IX investigator didn’t inform the official with the power to suspend Bigby-Williams.

Head basketball coach Dana Altman spoke with the UO deputy Title IX coordinator and Bigby-Williams’ former Gillette basketball coach several times in the 48 hours after UO was contacted by Wyoming police, according to phone records obtained by The Daily. Still, Schill’s administration did not impose consequences for Altman, who is still the head coach.

Bigby-Williams transferred to play at Louisiana State University at the end of the school year, and the investigation in Wyoming was dropped. He was never formally investigated by UO.

Flynn and UO’s athletics department didn’t respond to a request for comment.

A culture of body shaming at NU, UO

In September, The Daily reported allegations from four current and former NU cheerleaders, who described pervasive body shaming within the program. The cheerleaders alleged current head coach Valerie Ruiz made comments about the size of cheerleader’s uniforms, pressured them to fit into certain sizes and required them to line up by size rather than height.

Despite these complaints, Ruiz is still employed.

“We take all allegations of misconduct seriously,” Schill told The Daily in a statement. “The University has reviewed the culture of the Spirit Squad and taken appropriate measures.”

The UO athletics department faced allegations like these during Schill’s administration. In 2021, six women in the track program came forward to The Oregonian with similar claims. The UO track program had negatively impacted their mental health and eating patterns, they alleged.

Ashlyn Hare, a former runner at Oregon, told The Daily she noticed “problematic behaviors” throughout her time on the team. She said UO coaches were responsible.

“(Coaches) would hand out diets to athletes, they would make us record all of our nutrition and they would review it for us,” Hare said. “They would make comments to athletes at practice about how if they were fat, or if they ‘weren’t so fat,’ they would be faster.”

According to Hare, the program regularly measured runners’ weights and body-fat percentages. Players received mandatory scans three times a year using DEXA, a technology that measures bone density and body-fat percentage.

Hare said DEXA spurred much of the program’s toxic culture. She told The Daily she used to listen to her former teammates debate whether or not to eat prior to DEXA scans.

Ken Goe, the reporter who broke the story for The Oregonian, told The Daily some runners struggled with binge eating disorder, anorexia and body dysmorphia.

Hare said she tried to bring attention to these issues during her time at UO.

“When I graduated, I did my exit interview with the athletic director Rob Mullens,” she said. “And so I brought that up to him … I was just like, ‘(this is) a concern that I had with the program and with the coaches,’ and assumed that maybe that would kick something off.”

After Hare said it became clear that Mullens would not open an investigation, she decided to send a “pretty heated email” to an assistant athletic director.

“She referred it to the faculty athletic representative. So that’s when they allegedly kicked off some sort of internal investigation,” Hare said. “But beyond an initial interview … I’m not sure if that ever went anywhere.”

While reporting, Goe filed a public records request for any investigations pertaining to the complaints on the track team. Based on the university’s response to his request, no investigation on weight or eating concerns had ever been opened, he said.

Sexism was a major problem in the program, Hare added, noting only female athletes were asked to complete additional training to lower their body-fat percentages.

Coaches also punished female athletes who had body-fat percentages they considered to be “too high,” Hare said. She alleged those athletes would be left off the training or travel roster, and they’d be explicitly informed their body-fat percentages were the reasons why.

“If you didn’t perform as well as you wanted to perform at nationals or something, they’d be like, ‘well, we did everything that we could as your coaches, we gave you all the training and gave you all the tools so it’s kind of on you, and maybe has to do with your nutrition and you’re just fat,’” Hare said.

Goe said the success of the track team has long been important to UO. Nike co-founder and UO alumnus Phil Knight is crucial to fundraising and ran UO track in his college days, according to Goe.

And, Knight has long been intertwined with the success of the track program, Goe added. In 2017, Nike pledged $13.5 million to help renovate their facilities.

“Michael Schill was known for his ability to fundraise,” Goe said, “which primarily involved his ability to keep Phil Knight happy. Knight had a huge bearing on the track team — he wanted them to perform well.”

Though the head track coach’s contract was not renewed after Goe’s article in The Oregonian was released, Hare said Knight continued to have a hand in the team. Coaches Jerry Schumacher and Shalane Flanagan both stepped into the program in 2022 as head coach and an assistant coach, respectively. The Oregonian said both coaches planned to continue coaching professional athletes at the Nike-sponsored Bowerman Track Club.

“They replaced (the coach) with two coaches who were coaching professionally for Nike,” Hare said. “To me, that very much felt like an order handed down from Phil Knight. I also felt like there wasn’t going to be any repercussions for the track coach because he had been successful during his time there.”

Media relations at Nike did not respond to a request for comment about Knight’s involvement with the team.

Now, UO athletes can choose whether or not to receive DEXA scans, and reporting of individual results to coaches is not permitted, according to both Hare and Goe. While Hare said this change is a step in the right direction, she said it only came after the story went public in The Oregonian.

Schill told The Daily in a statement that UO engaged an independent firm to look into the incident, and they found no policy violations. A UO spokesperson confirmed an investigation was conducted and no policy violations were found.

“I should point out that the Oregon Track & Field program was one of the most important and successful programs at Oregon, and the decision to not renew the head coach’s contract was made not on his team’s performance but rather on his conduct,” Schill said in the statement.

Journalists’ restricted communication with athletes

Despite journalists — both students and professionals — breaking the majority of these athletics-related stories, another investigation into the athletics department opened during Schill’s tenure examined allegations of free speech violations at UO.

The university began its investigation after Dave Williford, the then-sports information director for UO football, suggested in 2016 he would revoke a press credential from a reporter for an alleged violation of university protocol.

The reporter, who worked at the university’s student newspaper, had contacted a UO football player directly to follow up on an interview. That action violated a UO protocol requiring all interviews with athletes be requested through the athletics department.

Though Shane Hoffmann, a former sports editor at The Daily Emerald, wasn’t present for the incident, he said media access for UO sports has always been difficult.

“Oregon definitely has a reputation for being pretty buttoned-up in terms of media access, especially in the athletics department,” Hoffmann said. “That’s something that I know was the case before I got there … and still is.”

Schill opened an investigation at UO in December 2016 to determine whether the protocol and Williford’s comment violated both athletes’ and reporters’ freedom of speech. The investigation found the athletics department did nothing illegal but could improve its media relations, The Daily Emerald reported at the time.

Reporters at the paper say limited athlete access significantly restricted their ability to cover athletics.

“The athletics department had its own public relations person,” the anonymous former Emerald reporter wrote to The Daily. “In general, athletes didn’t tend to be available for anything controversial if we were reaching out through their PR person.”

The report at UO also concluded that Williford’s suggestion to pull a reporter’s credential did not violate law or policy at the school, since athletes were still free to speak with journalists. Williford did not respond to a request for comment.

“It is clear from our interviews that student athletes are not restricted from contacting the media directly,” the report said.

NU’s protocol has long required student reporters to similarly secure interviews with athletes through the athletic department. And, starting with the 2023-2024 school year, the athletics department has terminated student reporters’ access to assistant coaches on the football team.

At the time, Schill told the Emerald’s reporters the University’s report was thorough and he supported it entirely.

Nearly seven years later, Schill told The Daily in a statement that Oregon never limited access to student-athletes for members of the media.

“If student-athletes wanted to talk to reporters, they were always permitted to do so,” Schill said in the statement. “If they did not want to talk to the media, our communications team limited access to them based on the individual student-athlete’s direction.”

Despite Schill’s praise, UO students and faculty criticized the investigation. Former Senate Faculty President Bill Harbaugh said the report’s finding that athletes can freely speak with reporters was wrong. He said he’d found that coaches “discourage players from talking about controversial things.”

Hoffmann shared the sentiment, noting distance between athletes and reporters kept much in the dark.

“There’s been a pretty consistent track record of a lot of things being swept under the rug or not really delved into fully, in large part because of that policy,” Hoffmann said.

Reporters at The Daily Emerald said school policies remained unchanged during Schill’s time at UO.

Now only one year into his tenure at NU, Schill contends with a number of lawsuits alleging hazing and racism, complaints from cheerleaders about safety concerns and accusations of overlooked assaults.

Parallels between UO and NU not only reflect ongoing, nationwide struggles to address athletic abuse and mistreatment, but also indifferent leadership, as Ryan, the former UO professor, described.

“If they took these issues seriously, these things wouldn’t happen,” Ryan said. “The problem is not just why did this happen in the first place, but how did (leadership) respond?”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @avanidkalra

Related Stories:

— Northwestern cheerleaders allege unsafe conditions, unfair expectations

— Former NU football player details hazing allegations after coach suspension

— Investigation finds evidence of hazing in football program, Pat Fitzgerald suspended