Local activism plays key role in Evanston’s climate leadership, student thesis shows

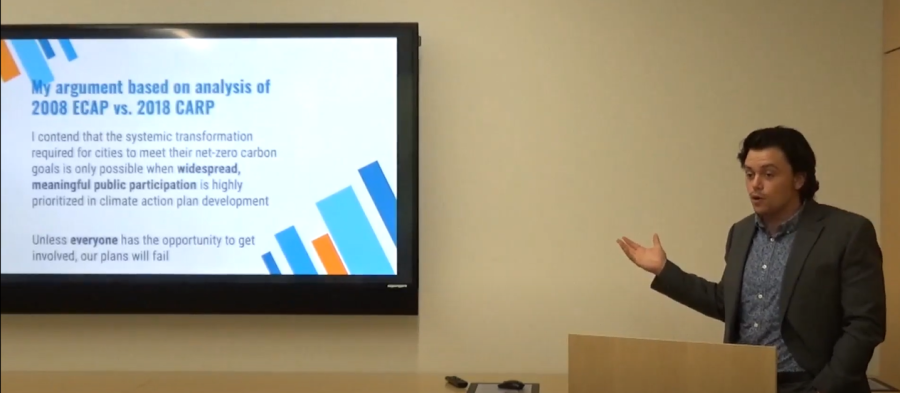

Jack Jordan (Weinberg ’22) presents his thesis to the American Studies Senior Thesis Symposium in May.

September 25, 2022

Evanston’s history of community involvement in climate activism transformed the city into an environmental leader, according to Jack Jordan’s (Weinberg ’22) honors thesis.

The American Studies paper, titled “Participating in Change: An Oral History of Community Climate Action Planning in Evanston, IL,” details the local organizing that informed city climate action plans in 2008 and 2018 in concert with global efforts including the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

Jordan presented his thesis, which he said will be published in mid-October, to Evanston’s Climate Action Resilience Plan Working Group and Mayor Daniel Biss.

Jordan, who said he interviewed over 20 activists and alderpeople, said action plans are one of the best mechanisms for cities to address climate change.

“The biggest reason why (the climate plans) were successful was a long history of residents, almost always on a volunteer basis, who were super passionate about climate activism,” Jordan said. “Evanston (has) a lot of climate professionals and professors.”

Evanston was one of the first cities in the country to have a climate plan and meet its preliminary environmental goals, Jordan said. The thesis attributes the plan’s success to passionate local volunteers: many activists involved in the 1990s remained involved through the mid-2000s.

In 2005, Evanston organizers successfully convinced former Mayor Lorraine Morton to sign The U.S. Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement, committing the city to the Kyoto Protocol’s greenhouse gas reduction goals.

Environmental Justice Evanston co-chair Jerri Garl said a key finding of the thesis is that 2008’s action plan enjoyed larger public participation, while 2018’s plan was an insular process conducted mostly at the city level. Over 100 people, including many residents, were involved in the 2008 plan, while only 17 working group members contributed to the 2018 plan, Garl said.

“I really believe (Jack’s) thesis was influential,” Garl said. “People on the (CARP implementation) task force acknowledged that he had made some excellent points about the need for engagement, especially in terms of implementation.”

According to Garl, the city lacks a much-needed coordinator for education and engagement on CARP and climate efforts. Filling this position, she said, will hopefully increase community involvement.

Jordan’s research revealed a major reason for the different levels of public input in climate policy between 2008 and 2018 was their political climates. After former President Donald Trump announced the U.S. would withdraw from the Paris Agreement in 2017, Evanston joined municipalities nationwide to show solidarity for climate action. Under these circumstances, former Mayor Steve Hagerty and City Council felt they needed to move quickly.

“(Councilmembers) said quite honestly, they had no idea what it would cost or how implementation would occur,” Garl said. “They knew we needed an implementation plan, but they wanted to vote on it to send a message.”

According to Jordan, Evanston’s most important climate action has been to engage in Community Choice Aggregation, providing the city clean electricity. Evanston purchased 100% renewable energy in 2014 through a contract with a local provider. Additionally, Citizens’ Greener Evanston ran a grassroots campaign in 2012 enabling residents and small businesses to opt into renewable energy, a key factor in the city achieving many of its climate goals, the report shows.

Jordan found Evanston climate activists were mainly older and white from professional, educated backgrounds. While educated organizers have helped Evanston’s climate efforts, diversifying the volunteer force will help meet more of the community’s needs, Jordan said.

“I think the policies will actually become much more effective and practical because they’re really made with the everyday person in mind, rather than just someone who’s been in the field,” Jordan said.

Bob Heuer, chairman of the Democratic Party of Evanston’s Climate Action Team, said the thesis could have a large impact on local environmental organizing moving forward. Heuer also said Jordan’s research needs to be shared with surrounding municipalities.

“All (of) Cook County needs to see this story, and we need to be moving on this,” Heuer said. “I mean, it’s like, ‘How do we organize young people under this climate umbrella?’”

Jordan’s thesis calls for collaboration with neighboring communities, including Skokie, with whom he said Evanston shares resources, supply chain networks and electricity grids.

Evanston presents a unique story that cities across the country can learn from, Jordan said. He said he wants the city’s environmental history to be available for both local organizers and other cities’ leadership to learn best practices from.

“I want people outside of Evanston and Chicagoland and Illinois and across the United States to be able to look at the kind of experience of this one city,” Jordan said. “No city has gone further down the path (than Evanston).”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @JackAustinNews

Related Stories:

— As electric cars grow in popularity, Evanston automotive industry expects to shift

— Northwestern to install four electric vehicle charging stations

— Evanston organizations provide sustainable modes of transportation