“A Site of Struggle” brings historical context to anti-Black violence

Image courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Contemporary Photography

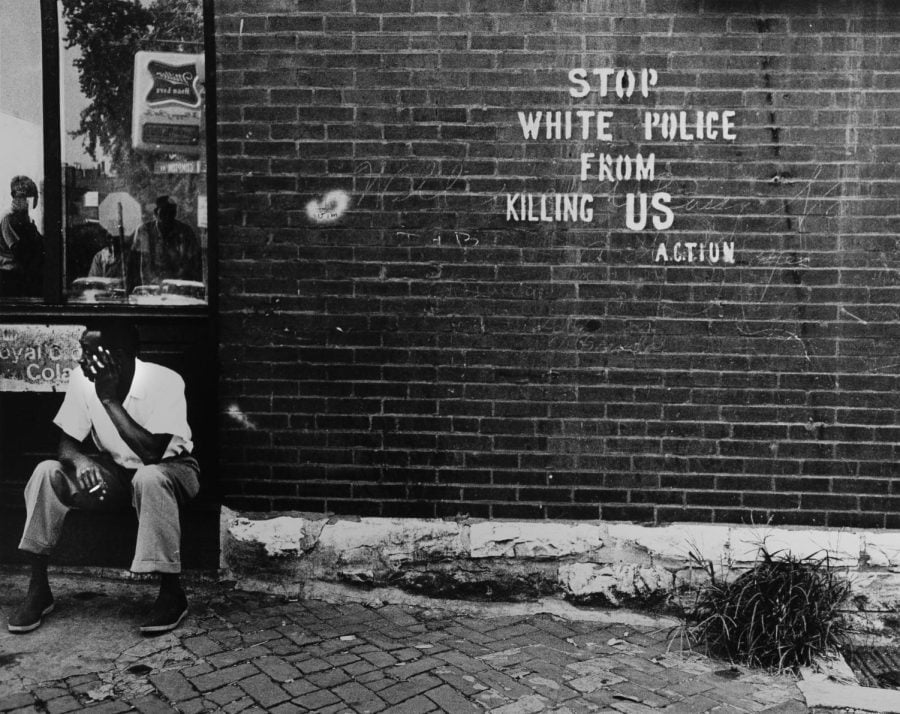

Darryl Cowherd Stop White Police from Killing Us – St. Louis, MO, c. 1966-67 Gelatin Silver Print Image: 15 x 19 in., mat: 20 x 24 ¼ in., paper 16 x 20 in © Darryl Cowherd

January 30, 2022

Featuring about 65 works of art, Block Museum’s latest exhibit, “A Site of Struggle: American Art against Anti-Black Violence” highlights depictions of anti-Black violence from the 1890s to 2013.

The exhibit asks: “How has art been used to protest, process, mourn and memorialize anti-Black violence within the United States?”

Janet Dees, the Steven and Lisa Munster Tananbaum Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, spent the last six years developing this exhibition. She said she wanted to establish an artistic historical context around contemporary conversations on racial violence.

“There’s this kind of thread in my practice around the interest in the ways in which artists sort of grapple with history and create work that help us to pause and reflect on history and what it means for our lives today,” Dees said.

The exhibit is divided into three sections: “Written on the Body” and “Abstraction and Affect” show anti-Black violence in more abstract ways, while “The Red Record” highlights art that features physical depictions of violence. “The Red Record” gets its name from a lynching pamphlet from Chicago-based activist Ida B. Wells.

Dees knew some of the material in the exhibit would be alarming for some, so she said she took special precautions to balance the quality of the exhibit with the comfort of viewers. One way was placing the more sensitive material of “The Red Record” in a “gallery within the gallery” so visitors would know what they would be seeing. The gallery features a resource room, where visitors can learn more about the historical context.

There is also a reflecting room at the end of the gallery, free of any art, which Lindsay Bosch, The Block’s senior manager of marketing and communications, said is a place where visitors can sit and collect their thoughts as they transition back to the rest of their day.

“We really want visitors to experience it at their own pace, in a way that they feel matches their own needs,” Bosch said.

She said the museum made sure to include as many voices as possible from the community while crafting the exhibit. It worked with an Evanston advisory board, local churches, educators and the local NAACP to ensure it could form as complete a picture as possible.

The opening conversation for “A Site of Struggle” took place online on Saturday. It featured Dees, community organizers and Northwestern faculty who helped craft the exhibit, as well as a conversation with Carl and Karen Pope about their featured work, “Palimpsest.”

There, Robin R. Means Coleman, vice president and associate provost for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer, spoke about the importance of acknowledging the long history of anti-Black violence in the United States.

“We are reminded that trauma begets trauma, but this cycle need not be ordained,” Coleman said. “The artists in this collection work to subvert actors of oppression.”

Dees intended for the exhibit to serve as an educational tool for NU professors and students. English Prof. Natasha Trethewey, for example, used the exhibit as context for her advanced poetry course this winter.

Coleman acknowledged the recent anti-critical race theory laws being introduced around the country and said having an informed citizenry is the best way to prevent ignorance.

“A Site of Struggle: American Art against Anti-Black Violence” opened Wednesday and will be on display at the Block until July 10. It will then tour to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in August.

Recent anti-Black violence events such as the police murder of George Floyd may lead some visitors to believe the exhibit is particularly timely. Dees emphasized, however, that this dark side of the United States has been a reality for many decades.

“It is, in some ways, coincidental that we’re right now at this moment of renewed attention to these issues within our cultural landscape,” Dees said. “But … this topic would have been relevant at any moment because there has been such an ongoing and long history of this violence within our country.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @AudreyHettleman

Related Stories: