Director of Warsaw’s POLIN Museum speaks about Polish memorial culture

Linus Höller/The Daily Northwestern

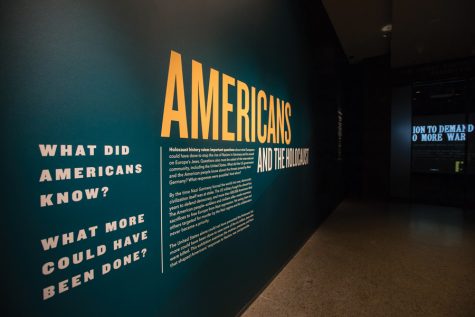

Dariusz Stola of Warsaw’s POLIN Museum speaks at EPL. Stola spoke about Poland’s Holocaust debate of the past and present and said he worries about the future of public discourse.

October 20, 2019

Seventy-seven years after the implementation of Nazi Germany’s “final solution of the Jewish question,” which resulted in the murder of up to six million people throughout occupied parts of Europe, Poland is still coming to terms with its role in the Holocaust.

Dariusz Stola, professor at the Polish Academy of Sciences and director of Warsaw’s POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, spoke about the Holocaust at the Evanston Public Library on Sunday. He discussed the way the Holocaust is taught, debated and remembered in his native country, Poland.

“There wasn’t really any space for this debate behind the Iron Curtain,” Stola said. “Really, there wasn’t any space for any debate under communist rule.”

Dariusz Stola of Warsaw’s POLIN Museum speaks at EPL. Stola spoke about Poland’s Holocaust debate of the past and present and said he worries about the future of public discourse.

According to the Holocaust Education Foundation of Northwestern University, which co-hosted the event, the POLIN Museum’s activities have “brought it international acclaim, museum awards — and more recently, vicious media attacks and political controversies.”

He mentioned, however, some notable exceptions to this rule.

Lively debates had raged in Poland immediately after the end of the war, initiated by a renewed wave of antisemitism within Polish society, Stola said. Later, before the fall of communism in the late 1980s, freedoms of speech and opinion began to reemerge, allowing for discussion about the Holocaust and the peaceful transition away from communist rule.

“I don’t think that these debates are over,” Stola said. “But I am worried about where they will go in the future.”

The difference of today’s debates is that they will largely play out on social media, Stola said, adding that false information and extreme points of view spread better online.

Loyola University Chicago Prof. Jim Blachowicz who was drawn to Stola’s presentation because four of his own grandparents were Polish, said he, too, was concerned about the impact of social media, which is changing the way people are educated about history.

“It’s a tragedy that the book is dead,” he said.

Stola is also concerned about new political trends in Poland and more broadly in Europe.

The party Confederation Freedom and Independence won 11 of the 460 seats in the Sejm, the lower house of Poland’s parliament, in the election earlier this month. The problem is that “they are proudly antisemitic,” Stola said.

“For the first time, a far-right-wing party entered Poland’s parliament,” Stola said.

In 2018, the Law and Justice party attempted to “suddenly push through a reform of (the Institute of National Remembrance),” Stola said, which would have penalized those alleging that Poland had been complacent during the Holocaust.

The proposal was met with broad public backlash, especially from foreign leaders and domestic academics, Stola said. Though the proposal was declared unconstitutional and not implemented, Stola said it was “considered as a green light by the anti-Semites of Poland.” He said it was a major setback in the way the public thought.

“It was weird for me to see that foreign heads of state were the ones defending the freedom of research in my own country,” Stola said.

Stola will speak at Northwestern on Tuesday at 7 p.m. in Harris Hall 108.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @linus_at

This article has been updated to clarify that Stola only called the Law and Justice party’s platform nationalist, while others have called it xenophobic.