Medill Prof. Melissa Isaacson speaks on panel about new book

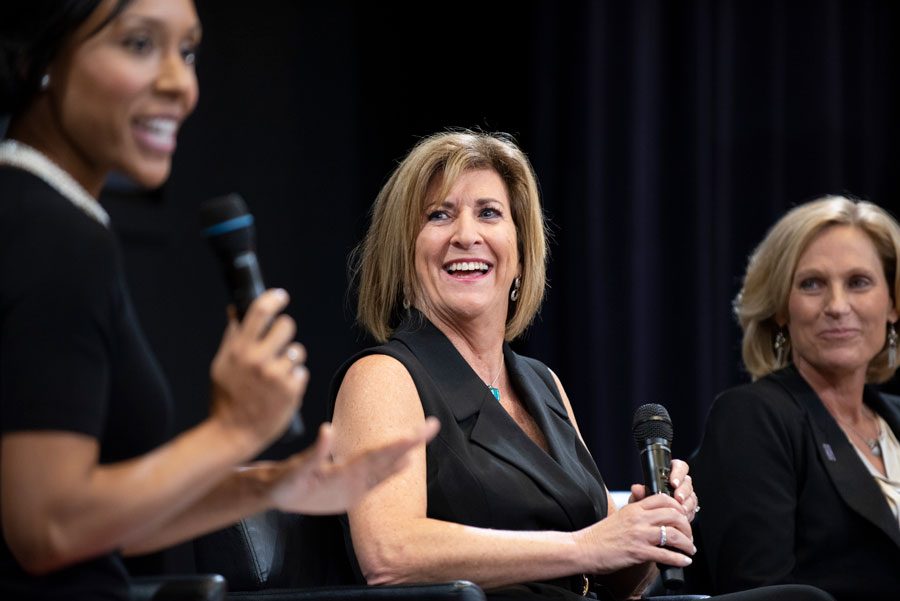

Colin Boyle/Daily Senior Staffer

Panelists Melissa Isaacson, Connie Erickson Brown and Amy Eshleman discuss topics in Isaacson’s new book, “State: A Team, a Triumph, a Transformation.” Isaacson’s book was published earlier this year.

October 13, 2019

Prof. Melissa Isaacson still remembers her first day at Niles West High School in 1975 and how all she wanted to do was find her place.

Isaacson quickly found that place on the girls’ basketball team, which became state champions in 1979 — only seven years after the passage of Title IX, a historic law that banned discrimination in federally funded programs. That team is the subject of her most recent book, titled “State: A Team, a Triumph, a Transformation.”

The team also served as the focus for a Friday panel featuring Isaacson’s teammate Connie Erickson Brown (Communication ’84) and Amy Eshleman, wife of Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot and a member of the first-ever Illinois girls’ basketball state championship team.

Lightfoot introduced the panelists in the McCormick Foundation Center Forum by sharing the significance of athletics in her life and the lessons she learned from playing sports growing up.

“Sports is more than just games,” Lightfoot said. “It really, truly, is about how we live our lives together as a community.”

Throughout the panel, one theme that emerged was how the Niles West High School championship team was an example of the community sports can create. However, “State” also documents the obstacles Isaacson’s team had to overcome while navigating the new systems implemented following the passing of Title IX.

Isaacson’s book details how players often had to wake up for practice at 4 a.m. — the only time they were allowed into the “boys” gymnasium. At that time, she writes, the women’s team had a separate, much smaller gym than the men’s team.

They also had to overcome wearing what Isaacson called “prehistoric” uniforms, which were made out of thick polyester and had been worn by every other women’s team at the school.

“I remember getting those first horrendous uniforms,” Isaacson said. “I thought I was on the Olympic team. I couldn’t have been more excited. I get chills, still, thinking about my first uniform.”

Isaacson’s book includes moments of joy and sadness for the players. When Erickson Brown was 10 years old, her 18-year-old sister passed away in a car accident. At the panel, she called the experience a “driving force” for her.

“(Sports) became an identity for me, and I knew who I was,” Erickson Brown said. “It was more than just playing a game.”

Since writing the book, Isaacson said she has met women a few years older than her who say they could have been great at sports had they been given the opportunity to compete.

“We were acutely aware of how lucky we were,” Isaacson said. “We really knew how special it was.”

The other panelists agreed that playing sports was ultimately more than just about winning games. Isaacson said a lifelong role model for her was her coach, Arlene Mulder, who always “demanded excellence” from the team, instilling a strong work ethic in her.

Eshleman added that her teammates were always “lifting each other up,” and playing basketball taught her skills beyond physical ability, like cooperation and developing lasting relationships.

“I can’t imagine my life without that experience I had in high school of being part of a team,” Eshleman said. “It shaped who I became. It’s absolutely the reason I am who I am. I really, really feel that.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ryannperlstein