Buchaniec: The wealthy have always had the academic advantage

April 4, 2019

The myth of meritocracy sits at the foundation of our educational system: if you work hard enough in high school, you’ll get into a good college and eventually, get a good job. It is a system that for the majority of Americans serves as an idealistic tool for economic and social mobility.

When FBI special agent Joseph R. Bonavolonta described the recent college admissions conspiracy as “a sham that strikes at the core of the college admissions process,” he displayed the same amount of discontent as many around the country. How dare these actresses and wealthy elite buy their children admission into some of the world’s top universities?

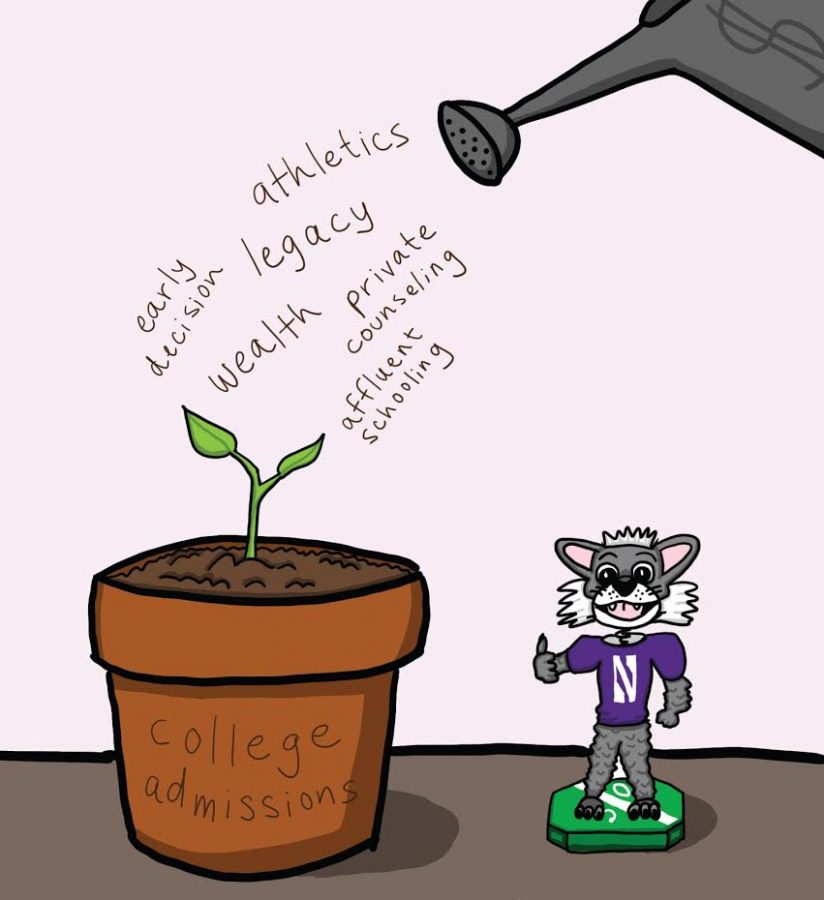

However, Operation Varsity Blues is just one instance of inequality in a system that is already rigged. The problem with college admissions is not simply that parents like Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman were able to cheat the system. It is the process of college admissions itself. From birth, your academic life is fated to be vastly different depending on your family’s income.

Discrepancies in public school funding

Putting aside private schools, the public school system itself is one of disparity. Although all public schools in the U.S. provide a basic education from kindergarten to twelfth grade, free of charge, an exorbitant amount of discrepancy exists among these institutions.

Public school systems receive the bulk of their funding through local property taxes, meaning that if a student lives in a more affluent neighborhood, their public schools are more likely to have an increased number of electives, Advanced Placement classes and most importantly, academic support. It doesn’t matter if all students take the same standardized test their junior year of high school or are evaluated holistically by the college admissions process — every student did not learn the same information or receive an equal education.

Consider New Trier High School, an elite public school in Winnetka that spent $25,665 per student in 2017, according to the 2017-2018 Illinois Report Card. With that money, they were able to hire well-qualified teachers and integrate technology into their curriculum — all to provide a more personalized education for their student. In comparison, the Illinois state average spent per student was $13,336.

New Trier High School spent $25,665 per student in 2017, according to the 2017-2018 Illinois Report Card.

Putting more money toward students results in high achievers. And, according to a 2012 Stanford University study, the achievement gap between the country’s wealthiest and poorest students is growing dramatically.

When it comes time to take the ACT or SAT subject tests, knowledge does not magically become standardized across the board. If a student has spent years receiving personalized teaching and participating in AP classes, they have an advantage over other students. With wealth comes the opportunity to attend a school with more resources, allowing a wealthier student to do better on standardized tests.

Additionally, those AP classes at more affluent schools assist students economically down the road. At many universities, Northwestern included, students can replace certain required classes with AP credit. In some cases, this can free up room in their schedule to graduate early, saving thousands of dollars in tuition money.

Outside of academics, New Trier offers opportunities that were not available at my high school nor at most high schools in the U.S. The school has 22 varsity sports that receive stable funding — including bass fishing — and maintains over 150 clubs and activities.

These clubs and sports permit to express their creativity in a manner that can be described in a college application essay. However, if a student only has ten or so clubs to choose from, they might never find an activity they’re passionate about — limiting the amount and variety of experiences they can reflect upon in their applications.

Furthermore, if a school receives large amounts of money from property taxes, it has more money to dedicate to athletics, especially to lesser-known sports such as lacrosse, fencing and rugby. In the college admissions process, athletes are regularly admitted with lower grades and test scores than other students. However, if a school doesn’t have the resources to establish such specialized programs, students are automatically denied this opportunity in the admissions process.

Public education in the United States ought to be an equalizer. It shouldn’t matter if a student lives in rural Kentucky or attends school in the heart of New York City — all students deserve the same opportunities to take the same classes and participate in the same extracurriculars.

Navigating Early Decision

The college admissions process doesn’t just happen in one regular cycle. There are multiple phases and all of them pit themselves against low-income students. In recent years, many elite schools, including Northwestern, have adopted an application process known as Early Decision.

This process, which allows students to apply in the fall of their senior year of high school as opposed to the winter, is binding. Once a student is accepted to a school during the Early Decision cycle, they are required to attend that school. Historically, the acceptance rate for getting into a school using Early Decision is dramatically higher than the acceptance rate during the regular application cycle. For Northwestern’s most recent admissions cycle, the Early Decision acceptance rate fell to 25 percent; in contrast, the regular acceptance rate rose to an estimated 6.9 percent.

In recent years, colleges have used this system to fill approximately half their class with “Early Decision” applicants. Approximately 53 to 54 percent of the class of 2023 is expected to be made up of Early Decision applicants, Christopher Watson, the dean of undergraduate admissions, told The Daily in an email in December.

For wealthy students who know what college they want to go to, this system allows them to utilize the higher acceptance rate. However, for low-income students, this process is inaccessible.

When I started applying to colleges, I could not participate in the advantageous early decision system because of its binding nature. If I were to be accepted to a university during Early Decision, I would have been bound to that school and whatever financial aid package it decided to give me. As a student who wanted to limit the amount I took out in loans, I needed to compare the financial aid packages of multiple schools. For me, choosing what school I was going to go to primarily depended on whatever one was cheapest, not which one I liked the most.

Advantages during the application process

During the application process, the differences among students coming from wealthy backgrounds versus those hailing from low-income families become more apparent, especially in regards to assistance.

Early on in my academic career, I was in the minority of students — going to an elite university was not something most students did or even thought of doing at my high school. Counselors focused on helping students graduate high school, not apply to Ivy League colleges. The CSS financial aid profile was unheard of and SAT subject tests were taken by only four students in my grade.

Knowledge about the specifics of the college application process was hard to come by and the internet became my best friend for finding information. Initially, I thought that this was typical of the college application process.

However, during my junior year, I signed up late for the ACT and instead of taking it at my high school, I found myself in the hallowed halls of New Trier.

Students taking the ACT test.

On a Saturday morning, my mother, who herself was in the process of earning her bachelor’s degree online, drove me past the mansions of Winnetka to the epitome of academic privilege. While waiting outside for the doors to open, my disillusionment began to set in as I overheard students comparing ACT tutors, college counselors and outside admissions consultants.

When Googling the services they talked about, all I saw were price tags for services that I could not afford. There were people to assist in editing essays, tutors to quiz SAT vocab words and entire businesses dedicated to helping students craft a persona to flaunt to a college admissions board — independent of the resources they were already receiving in school.

In addition to their parents, these students had countless people helping them tackle the process. I had only myself. To study for the ACT, I borrowed books from my local public library and sat at my desk for hours. In writing my essays, I consulted YouTube videos and online testimonials.

Whereas many wealthy students’ applications had the assistance of a small army, my application was written just by me.

More than a scandal

For those who say that the recent college admissions scheme is a stain on an otherwise impeccable system, it is time to acknowledge that our college admissions process and education system are broken and have been for years.

Michelle Janavs, a former executive of a food manufacturer charged with participating in the college admissions scheme.

When it comes down to who has privilege in the college admissions process, it is not just those who donate millions of dollars like Jared Kushner’s parents did to get him into Harvard. As fellow columnist Andrea Bian pointed out this past fall, legacy admissions continue to account for a significant number of admitted students. Although Northwestern has not publicly released their statistics regarding legacy admissions in recent years, in 2007, they accounted for 24 percent of that year’s class, The Daily reported.

For low-income students, each part of the college admissions system is corrupt and rigged against them. They don’t have a legacy last name; they don’t have the ability to donate millions of dollars; they don’t have Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman’s illegal side-door bribery; the majority aren’t athletes; they didn’t attend the wealthy public schools in the country; and above all, they didn’t receive thousands of dollars in outside college counseling services.

The college admissions system — and the entire U.S. education system — is catered toward the wealthy few, not the middle class and low-income majority. People say that money talks, and in the world of college admissions, it is the only thing worth saying. Although education might have started as a means of social and economic mobility, in 2019, it is nothing but a system of classism.

Catherine Buchaniec is a Medill first-year. She can be contacted at [email protected]. If you would like to respond publicly to this op-ed, send a Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. The views expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect the views of all staff members of The Daily Northwestern.