By marginalizing the queerness of Freddie Mercury, ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ disrespects the icon it tries to celebrate

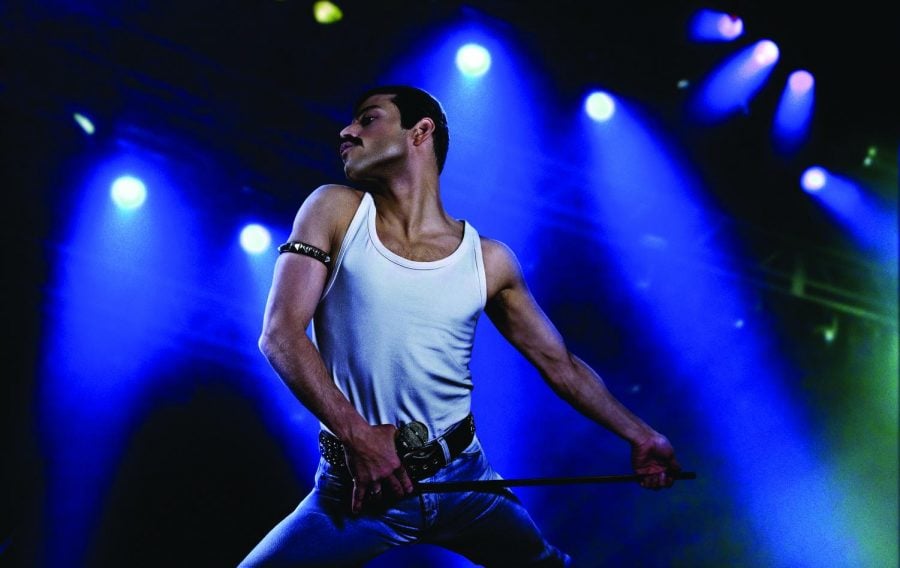

Rami Malek plays Freddie Mercury in “Bohemian Rhapsody”.

November 28, 2018

After an hour of watching rock icon Freddie Mercury moon over his girlfriend and resist the advances of his manager, there finally came a scene where Mercury — played by Rami Malek — has his meet cute with future boyfriend Jim Hutton (Aaron McCusker). As the two had a short and sweet conversation about sexuality and identity, I began to perk up, hoping the film would finally portray him owning himself and exploring his sexuality.

But, no. After that brief, lovely encounter, Hutton disappears until the final scene, and the film goes on to not just resist Mercury’s queerness, but to actively disrespect it. “Bohemian Rhapsody,” directed by Bryan Singer with Dexter Fletcher finishing production after Singer was fired for poor behavior on set, seems determined to take Mercury’s fascinating life story and turn it into the most generic, formulaic biopic possible.

The film plays fast and loose with Queen’s history, often in ways detrimental to their real story. The completely fictional temporary breakup of the band in the third act comes across as trite and clichéd. And Mercury’s infamous HIV diagnosis in 1987 is delivered to him in 1985, just days before Queen’s legendary performance at the “Live Aid” concert. While this change had the potential to up the stakes and add drama to the concert, it instead framed the diagnosis as a punishment for Mercury engaging in the “evils” of gay subculture.

The way the film depicts Mercury’s queerness is by far its worst sin. The movie’s disdain for accuracy and overall lack of energy lend to merely a boring and uninspired movie, but its poor handle on portraying Mercury’s sexual identity makes the film damaging. Utilizing every antiquated stereotype about gay men and gay subculture in the book, the end result is a film that inadvertently implies that Freddie Mercury was corrupted by his own sexual orientation.

“Bohemian Rhapsody”’s complete disinterest in adequately exploring Mercury’s queer identity is reflected in the character who it positions as the love of his life: Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton), his ex-girlfriend. The film plays lip-service to the impact other key figures had on Mercury’s life (such as his parents and his band’s manager), but they ultimately come across as background characters. The other members of Queen, in particular, get so little focus that I could barely put names to faces.

Having Mercury’s most prominent relationship be with a heterosexual woman is a move that many other mainstream films have made to make queer themes more palatable for a straight audience (“The Imitation Game” and “Love, Simon” among them). Admittedly, Austin was a prominent part of Mercury’s life, and the two had a very significant friendship after their romantic relationship. But the focus she gets means the queer men in Mercury’s life, specifically Hutton, are marginalized as afterthoughts, and makes “Bohemian Rhapsody” seem like the grand story of how Mercury’s love for a straight woman saved him from the evils of the gay lifestyle.

Mercury is portrayed as being obsessed with Austin, to the point of being possessive and totally reliant. Every poor decision Mercury makes is stemmed by his grief and rage over his inability to be with Austin, creating an impression that Mercury’s sexual orientation is a tragic obstacle preventing him from being with the woman that he loves, rather than a natural and beautiful part of who he is.

Mercury and Austin’s relationship also ties into the film’s vaguely infantilizing treatment of Mercury’s sexuality. Too often, Mercury isn’t portrayed as a mature, confident queer man, but rather a little boy who has no control over or confidence in his orientation. When he was seduced by his sleazy manager, Paul Prenter (Allen Leech), Malek over-exaggerates Mercury’s sexual confusion and insecurity, to the point where he comes across as a naive teenager. This would be forgivable if it was the beginning of an arc where Mercury becomes confident in his queerness, but that never comes to fruition. Mercury’s eventual happy relationship with Hutton is underdeveloped and robbed of necessary screen time, and the film lacks any pivotal moment that depicts Mercury growing up and owning his identity.

The film also plays up the predatory vibes with Prenter, who is positioned as the villain of the movie; he practically twirls his moustache whenever he’s on screen. Regardless of whether there’s any truth to his toxic presence in Mercury’s life, it’s hard not to feel his portrayal makes the statement that gay culture leads to misery. Prenter is behind practically every crisis in Mercury’s life, isolating him from his bandmates and leading to the end of his and Austin’s relationship. Prenter is the one who introduces Mercury to the gay subculture, which is depicted as seedy and borderline evil. A montage of the two going to a gay club is shot in such a way to suggest that this excursion is Mercury’s low point, a tragic mistake that will ruin his life. In real life, it was in one of these “hedonistic” gay clubs where Mercury met Hutton, the love of his life, another detail conveniently changed to fit the film’s agenda.

It’s infuriatingly easy to imagine a version of Bohemian Rhapsody that doesn’t treat such a core part of its main character’s identity with total contempt. Malek and McCusker have good chemistry in the limited scenes they do share, enough that you can picture McCusker’s role being expanded into something more significant. The depiction of gay subculture as a negative influence on Mercury would be easy to fix with a few rewrites. And by not changing when Mercury received his HIV diagnosis, the film could have avoided its reprehensible treatment of the disease as a punishment for his actions. It’s all the more baffling when you consider that Bryan Singer is an openly gay man.

Somewhere buried in Bohemian Rhapsody is the potential for a film that shows one of rock music’s few queer icons discovering and embracing his identity, and does justice to a legend. Instead, we’re left with an insulting and nasty movie, one that disrespects the icon it should be celebrating.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @wilsonchapman10