Dittmar exhibit challenges stereotypes about black men

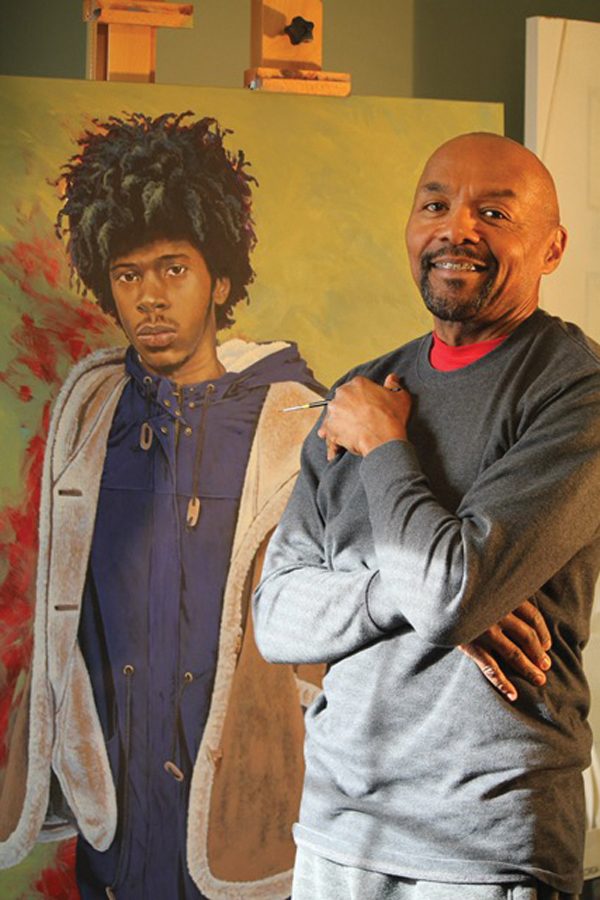

Rick Lewis with one of the portraits from “(In)Visible Men.” The portrait series seeks to challenge stereotypes about black men.

February 14, 2018

A&E

Rick Lewis’ students at Illinois State University knew him as a helpful administrator and mentor for black students. They were unaware of his artistic talents until they became the subject of his art.

Lewis’s portrait series, “(In)Visible Men,” features 13 portraits of black men, most of whom he knew as students at ISU. The series will be on display at the Dittmar Gallery Feb. 16 through March 22, and seeks to bring visibility to the subjects of his portraits and challenge stereotypes about black men.

Lewis, who was the associate dean of students at ISU for 11 years, said his career as an advisor for black men inspired him to create art as a form of social commentary.

“(These students) talk about feeling ostracized, feeling invisible in the classroom and not feeling like a part of the campus community,” Lewis said. “So I’ve tried to work with these guys and help them understand how to work in these predominantly white institutions, and these issues have been incubating (in me) for 30 years.”

Lewis has a master’s degree in art from ISU, but he put his painting career on hold when he was offered a position as a residence hall director after graduating in 1987. He briefly returned to painting in 1992, then went back to serve in administrative roles at ISU. In 2013, with retirement on the horizon, Lewis took up painting again for the first time in almost twenty years.

One of the students he had mentored, Sam Geralds, said he walked into Lewis’ office one day in 2013 and saw Lewis looking at some of his own paintings. The two men discussed Lewis’ artwork, and shortly afterwards, Lewis asked Geralds if he would be a subject of a painting. He completed the portrait in August 2013, and it became the first in the “(In)Visible Men” series.

Lewis said the collection of portraits may create a sense of discomfort for a viewer who has not spent a lot of time with people of color, but that the feeling of discomfort is central to the purpose of the exhibit.

“You paint one portrait and it’s a standalone portrait and it’s realistic, and people look at it and say ‘Oh, that’s a nice portrait,’” Lewis said. “But once you fill a space with all of these portraits and these portraits are looking at you and you’re confronted with this experience, that’s part of the art.”

He said he hopes to challenge stereotypes about black men by elevating their images to the status of art.

There is a lack of visibility for people of color featured in the art traditionally displayed in galleries, Lewis said. He said race is also a factor in one’s access to art, as many of the students depicted in his portraits had not been to an art gallery before he invited them to see his work.

Lewis said the opening of the “Contemporary Portraiture” exhibit at the McClean County Arts Center in Bloomington, Illinois, where eight of his paintings were featured, made systemic inequality clear to both the student population he painted and the gallery’s usual crowd.

“I’m sure it was a lot of those folks’ first times seeing these types of portraits, and you have these students who had never been to an art show or reception of that level,” Lewis said. “I’ve done diversity training for the last 20 years, and I’ve never seen that kind of dynamic played out in terms of people learning about other people.”

At the gallery, the students featured in the portraits and the predominantly white gallery goers had an opportunity to interact and share experiences, Lewis said.

Jamol Griffin, another former ISU student featured in the portrait series, said his family was impressed by the details of the portrait. Lewis even managed to capture the distinctive veins in his arms, Griffin said.

Geralds said he was approached by some of the people in the gallery who recognized his portrait and that he felt proud to be a part of Lewis’ art.

“It was dope, because this is something he visualized and brought to life,” Geralds said. “I don’t know how much of it came out of that conversation (in 2013), but it was pretty cool to help spark that.”

Email: [email protected]