Ask yourself this question: “If hell is being stuck in one room for the rest of your life, then would you even want to be with other people?”

The Virginia Wadsworth Wirtz Center for the Performing Arts’ Student Performance Project of the existentialist play “No Exit” tackles this disheartening thought experiment and turns this play into a profound, raw show that sparks more questions than answers.

The show, written in 1944 by Jean-Paul Sartre and adapted by Paul Bowles, tells the story of three individuals trapped in the same room in hell together. Brought into this room one by one and expecting torture, they soon realize their true punishment is spending eternity with the same group of people.

These characters, Cradeau (Communication senior Margaret Pirozzolo), a disgraced, murdered journalist, Inez (Communication senior Sydney Brenton), a secretary seemingly in hell for an affair with her cousin’s wife and Estelle (Communication senior Caroline Humphrey), a young, seemingly ideal woman who died of pneumonia, are wildly different. Yet, they all attempt to process the world they left behind, their reasons for being in hell and the eternity they have to spend there.

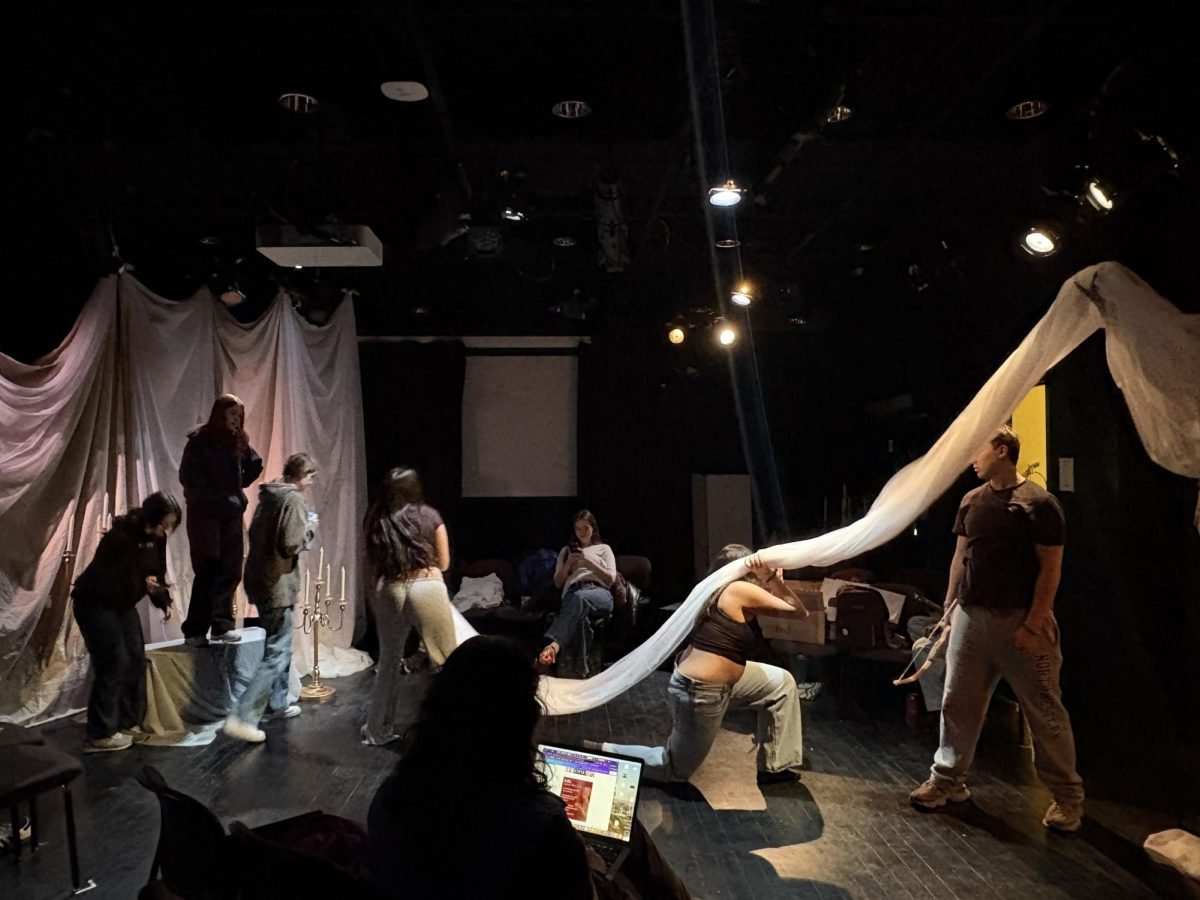

“No Exit” is the type of play that could be executed well without a set, and this production almost does that. The black box theater only holds three couches, a door and a small table upon which rests a couple of miscellaneous objects. This gives a clean slate for the actors to take complete advantage of, never once overshadowed by the lighting or set.

Humphrey takes these bare bones and runs with them, shining as a woman who is seemingly caught between who she wants people to perceive her as and who she truly is. She constantly shows an ever-changing and incredibly wide range of emotions. Even when the focus seems to be on the other characters, Humphrey seems to take it as a challenge to convey inner thoughts to the audience without any dialogue. She turns the role of Estelle into one of the most complex and engaging ones in the show with her mental breakdowns, the constant hunt for a mirror and raw reflections of her life.

Almost more interesting than the questions about morality and hell are the questions the show brings up about gender. Cradeau constantly struggled with what it meant to be a man and courageous when he was alive, and Pirozzolo perfectly portrays a man stuck in hell who wants to spend eternity quietly mulling over his mistakes during his life. Pirozzolo delivers his pondering monologues and the most famous line of the show, “Hell is other people,” with a conviction that resonates.

The show highlights the complex bond between the three as Inez becomes infatuated with Estelle, but Estelle and Cradeau end up briefly getting together in front of Inez. Brenton’s best moments are when her humor and mockery of Cradeau provide a nuanced, layered perspective on heartbreak.

What keeps the audience invested in these three villainous characters is not the promise of something more — the first five minutes of the show make it clear they will spend eternity in this version of hell — but the curiosity of how the actors are going to fill the rest of the show. You know the grim fate of the characters, but they remain enthralling and poignant in their exploration of some of life’s biggest questions.

Email: lydiaplahn2027@u.northwestern.edu

Related Stories:

— Annual Vertigo Productions series showcases three student-written plays

— Wirtz Center’s ‘Museum’ shows the range of humanity but gets lost in absurdity

—Jewish Theatre Ensemble’s ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ dazzles with music, wows any crowd