Every Friday evening, Northwestern’s Dearborn Observatory holds free “Friday Nights at the Dearborn Observatory” where the public can come and look through the Dearborn telescope.

The event lasts two hours — the first hour of tours being reservation only and the second hour of tours being drop in.

Fifth-year physics Ph.D. candidate Kierstin Sorensen, who works at the observatory, said she always wanted to work at the observatory because loves doing public outreach and sharing her knowledge of astronomy.

Sorensen said she particularly likes looking at binary systems — when two stars orbit each other — with the Dearborn telescope. The telescope can also see planets, moons and very dim star clusters, she said.

“I hope I spark a fascination that leads to further exploration,” Sorensen said. “I hope (people) see something interesting that they’ve never seen before and it gives them a little new perspective, a new experience, and it has them come back to see something else another time.”

The Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics also hosts Astronomer Evenings at the observatory every last Friday of the month at Dearborn Observatory.

CIERA Astronomer Evenings are free educational talks on different astronomy topics each month. This past Friday, fourth-year physics Ph.D. candidate Imran Sultan gave a presentation about astrophotography of the sun.

“This year in particular has been an incredible year to look up at the sun, observe the sun and try to photograph it,” Sultan said.

Sultan won the 2023 Royal Society Publishing Photography Competition astronomy category with a photo of the Western Veil Nebula, remnants from a big star explosion.

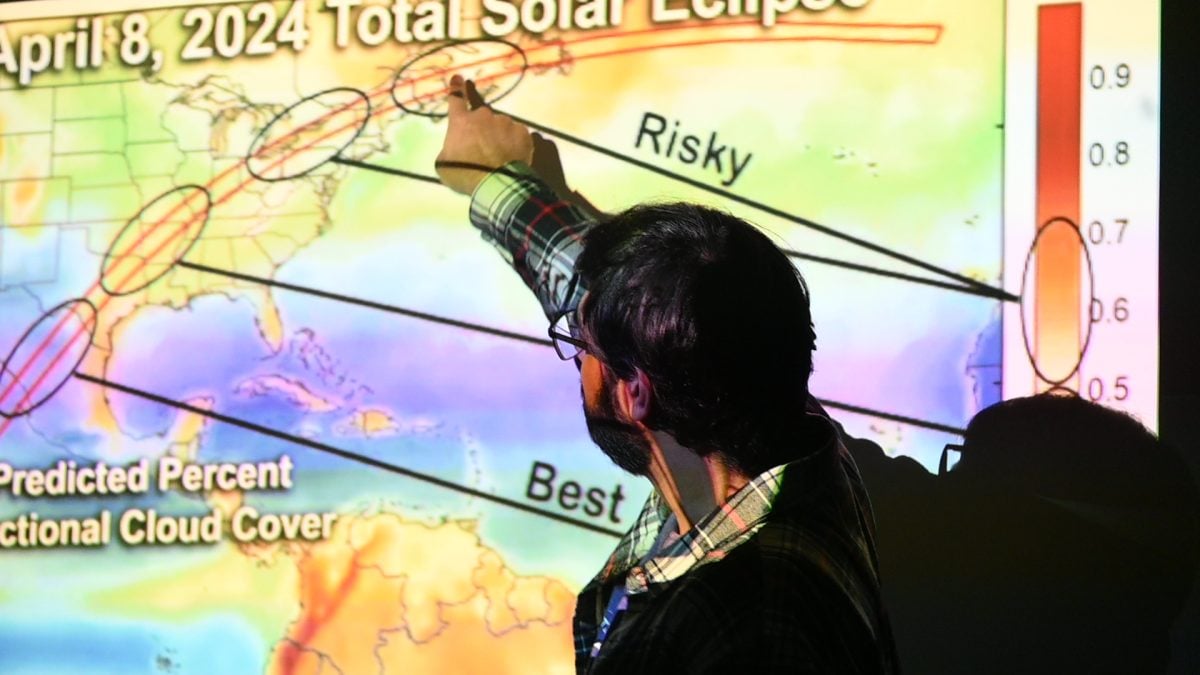

Sultan talked about photographing the solar eclipse and the Northern Lights during his presentation.

Chicago resident Taylor Billington said she enjoyed coming to the observatory and the telescope, and especially enjoyed the talk.

“The images in the talk were very beautiful, and it was nice to see them,” Billington said.

Sultan said he traveled to Maine to see the solar eclipse in full totality with clear skies this year.

“That day there were these sunspots right in the middle of the sun,” Sultan said. “All of us photographers were delighted to see the spot because it made focusing on our camera and telescopes a lot easier than trying to just eyeball (the focus).”

Sultan said he was successful and took photos of all the stages of the eclipse, solar flares and the solar corona — the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere usually hidden by the light of the Sun.

The totality of the eclipse only lasted about three or four minutes, Sultan said.

“We can only really take (images of the solar eclipse) because the moon just happens to be the same size as the sun in the sky and that’s a complete coincidence,” Sultan said. “There’s no reason that we can think of why that’s the case.”

Sultan also spoke about the Northern Lights phenomenon which are caused by solar flares interacting with the Earth’s magnetic field. The Earth’s magnetic field protects the Earth from these solar flares but when the flare comes into the North or South pole, it creates Northern lights, he said.

This year at the end of May the Northern Lights were visible in the northern Midwest area of the U.S. Sultan said he traveled to rural Wisconsin to get the best photos because the skies were dark and there was a high probability of seeing the lights.

“(The Northern lights) were stretching all around me in the sky and it was absolutely incredible to see,” Sultan said. “I would say it’s comparable to the experience of seeing a total eclipse because I never thought I would see it from this location without having to travel up north.”

Email: ninethkanieskikoso2027@u.northwestern.edu

Related Stories:

—Eyes on the skies: 2024 solar eclipse brings NU community together

—Stars align for Faculty Family night at the Dearborn Observatory

—Dearborn Observatory and CIERA host public viewing of total lunar eclipse