A May 23 lawsuit filed by six descendants of non-Black Evanston residents could prevent the continued implementation of the first reparations program in the U.S. While this is the first court challenge to the city’s initiative, it comes amidst a wider debate in the country about whether the U.S. Constitution is “colorblind,” some legal professionals say.

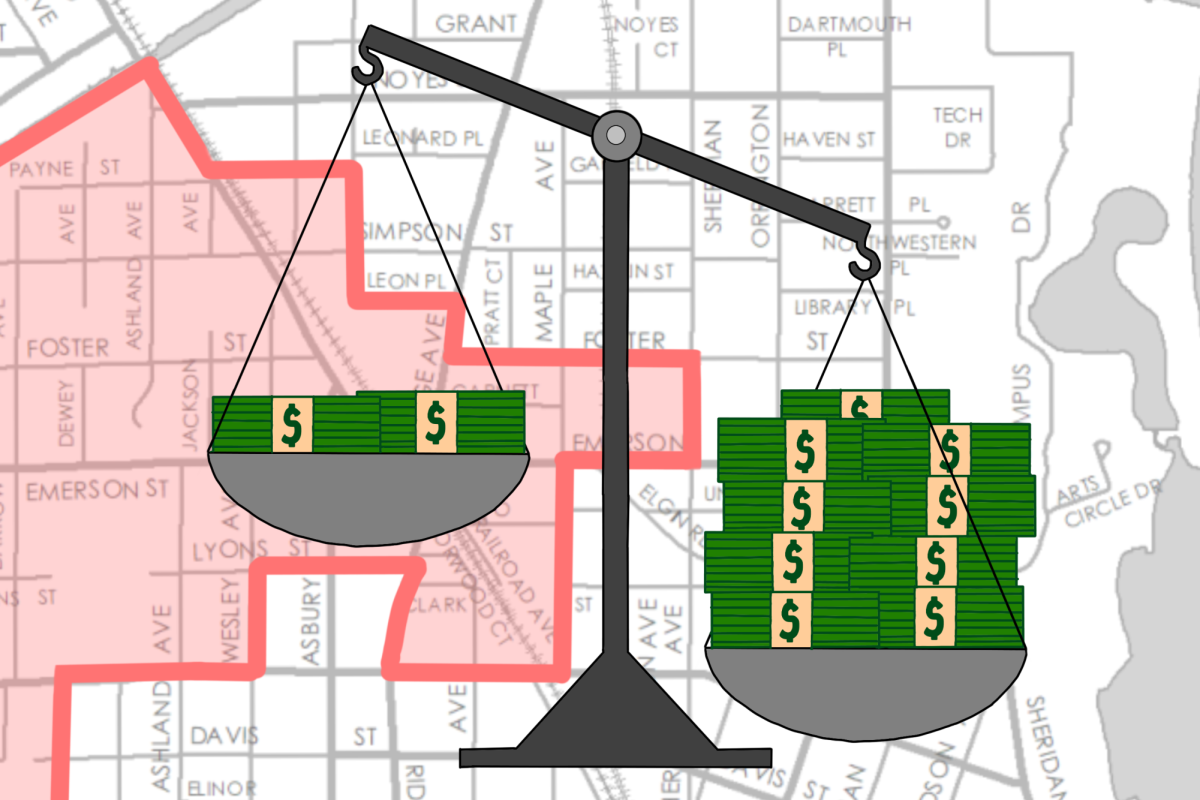

Evanston’s reparations program, approved in 2019, provides grants of up to $25,000 for Black residents who lived in Evanston from 1919 to 1969 or are direct descendants of the first group. City officials have said the program’s goal is to remedy harms on Black residents caused by discriminatory housing practices in that time period.

The lawsuit alleges that the reparation program’s use of race violates the Constitution’s 14th Amendment, which prohibits state and local governments from “(denying) to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” For race-based government policies — like Evanston’s reparations program — officials have to meet strict scrutiny, meaning that their action is narrowly tailored to fit a compelling government interest.

The plaintiffs in the case dispute both parts of that standard, claiming that race isn’t a narrow enough criteria to prove housing discrimination occurred, the city didn’t consider race-neutral alternatives and remedying societal discrimination isn’t a compelling enough goal.

But Pritzker Prof. and Associate Dean of Research and Intellectual Life Paul Gowder said there are some fine lines that might make the case less clear cut.

“This goes back to the period when courts were ordering busing to desegregate schools after Brown v. Board of Education,” he said. “One of the things that was clear from those cases is that correcting an entity’s … own prior discrimination counts.”

That’s opposed to a more general goal of remedying any societal discrimination, he said, a goal that might not hold up as well in court.

Gowder also said there’s room for argument about whether race adequately proves past discrimination.

“Again, think about busing — when cities and counties that operated schools engaged in busing to desegregate their schools, they didn’t have to show that each individual child who they put on a bus had a direct connection to discrimination,” Gowder said.

He added that Evanston could argue it’s trying to undo the overall conditions created by discriminatory housing practices in the past.

One of the organizations representing the plaintiffs is Judicial Watch, a national conservative activist group. Michael Bekesha, one of its senior attorneys, said Judicial Watch has succeeded in stopping race-based government action across the U.S. Those victories include a California policy that requires public companies to have certain numbers of women and people of minority racial groups on their boards, as well as a North Carolina program giving scholarships to Black students, he said.

“Evanston wanted to be the role model — they wanted to be at the front of providing reparations to residents,” Bekesha said. “We hope our lawsuit will give those other government entities, cities or states some pause.”

The reparations lawsuit comes months after the U.S. Supreme Court found race-based affirmative action in higher education admissions unconstitutional. In two cases filed against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, the court agreed with the colorblind Constitutional framework that Bekesha and his colleagues advocate for.

Gowder said the current court would likely not be favorable to Evanston’s reparations program. Still, there are a plethora of steps before this case could make it to the justices in Washington, if ever.

For one, both Gowder and Bekesha said Evanston could shift to a race-neutral housing discrimination reparations program. Bekesha said the current initiative already has one eligibility group that could qualify.

“It is, prove that you are an Evanston resident and that you suffered housing discrimination after 1969,” Bekesha said. “That would be a way, potentially — of course it depends on how it’s applied — to have a program that may be lawful.”

There’s also a question of whether the plaintiffs have standing to sue — that is, if they can prove a “concrete, individualized harm” as a result of the city’s actions, Gowder said. Previous federal cases have set limits on who can claim standing. For instance, the government using collected revenue in ways taxpayers dislike generally doesn’t meet standing requirements, Gowder added.

None of the plaintiffs applied for the reparations program or were rejected from it, but would have applied if not for the race requirement, according to the plaintiff’s complaint.

“It would be interesting to consider arguing, ‘This is just the same kind of generalized grievance sort of dressed up as an individualized injury,’” Gowder said.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers officially served Evanston with the lawsuit on May 28. The city will have a few weeks to make its initial response to the allegations, Bekesha said.

In a statement to The Daily, Evanston spokesperson Cynthia Vargas said the city does not comment on the specifics of pending litigation. The city has canceled its Thursday Reparations Committee meeting and replaced it with an information session about the lawsuit, according to a Tuesday news release.

“We will vehemently defend any lawsuit brought against our city’s Reparations program,” Vargas said.

Shannon Tyler contributed reporting.

Email: [email protected]

Related Stories:

— Descendants of Evanston residents file federal class action suit against reparations program

— Reparations committee determines order for reparations distribution