In the basement of Main Library, Northwestern’s conservation lab remains hidden in plain sight, tucked away in the corner of the basement.

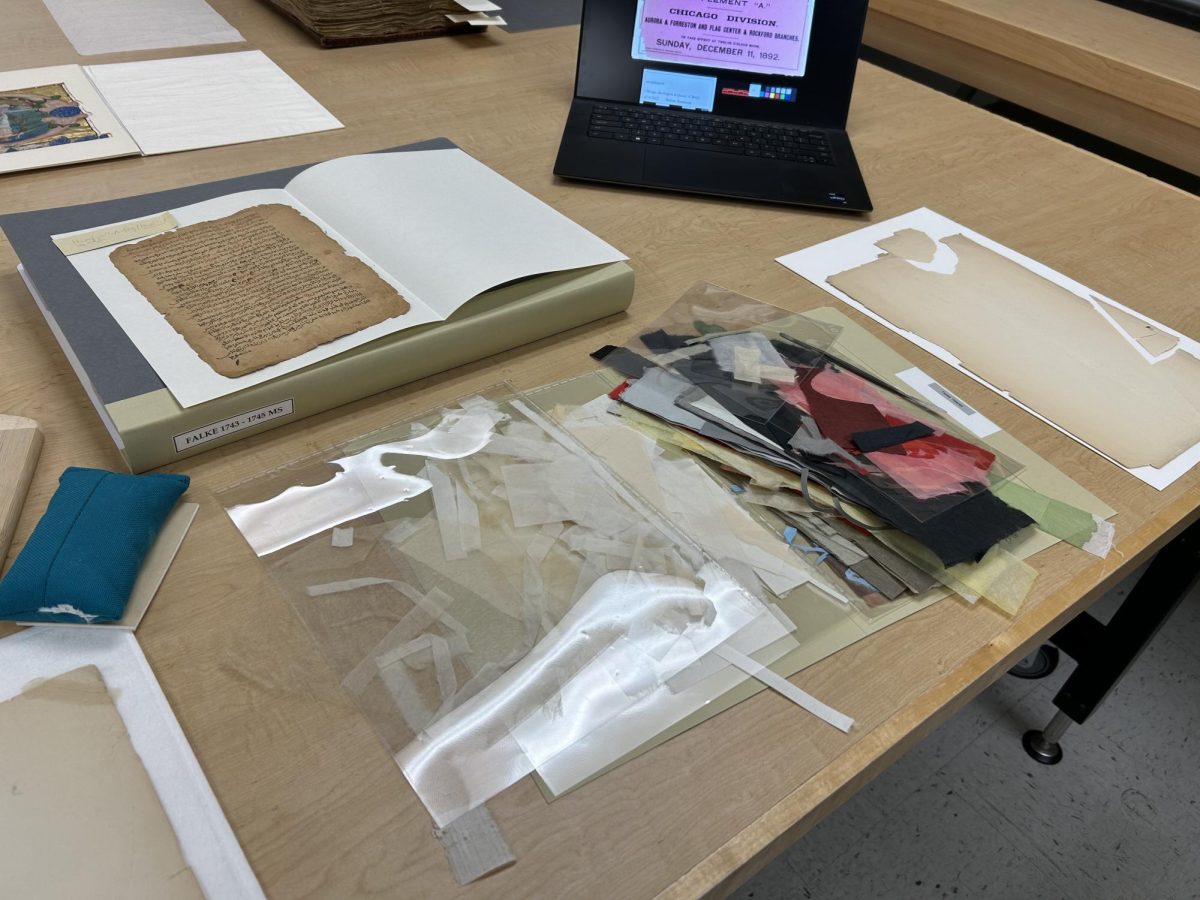

Among old book presses, brushes and fume hoods, a series of artifacts stand out. There’s a large yet well-kept Arabic manuscript from the 1500s stationed right next to Garry Marshall’s baseball mitt. Near the chemicals, a collection of innocent-looking yet toxic green-colored books pile up in Ziploc bags. One of them has a label with a skull-and-bones warning sign, reading: “Danger: Contains Chromium, Lead and Mercury.”

This is the lab where conservators work quietly year-round to protect and repair items from NU’s archives from the elements. Raising awareness of how libraries and other cultural institutions preserve archives is the crux of the American Library Association’s Preservation Week, which took place this year from April 28 to May 4. This year’s theme is “Preserving Identities,” which emphasizes community, cultural and individual identities.

Preservation librarian Katie Risseeuw said she hopes this theme can help people place more value on their own stories and archives.

“No one should be like, ‘Oh, I’m just a little person somewhere,’” Risseeuw said. “Yes, we might have famous peoples’ archives here, but a random student, a woman from 1913 — we have her scrapbook. It’s important that everyone knows that their story matters.”

That’s why the preservation department preserves and conserves all kinds of materials with care and precision, according to chief conservator Susan Russick. Preservation consists of preventing materials from degrading, while conservation is a direct intervention like repairing a tear, she said.

Mending a single page in a manuscript can take up to three hours, according to Russick. However, she said there’s a joy that comes with the combination of hands-on crafting and problem-solving.

“You do feel an intimacy with these cultural heritage materials,” Russick said. “You can see where people made little mistakes or added a little flair or something, and I love that.”

NU’s lab boasts state-of-the-art technology, including techniques like multispectral imaging, which harnesses the electromagnetic spectrum to reveal faint writing or uncover what was scratched out.

Book and paper conservator Stephanie Gowler said she appreciates how the distance between her and the past shortens when she comes across items featuring everyday people.

For example, when Gowler worked at the Indiana Historical Society, she recalled a beer sign from one of the first gay bars in the state that was signed by people with little messages. Gowler said the sign reminded her of her own coming out experience as a college student in Indiana.

“It was viscerally not just humanizing the past but seeing yourself in the past, right?” she said. “Seeing yourself in an archive in a way that maybe you haven’t before.”

There can be some material that is racist and discriminatory, which Gowler said can lead to questions over whether to preserve it. According to Gowler, the older mentality is to be neutral, but both she and Risseeuw said new attitudes around conservation have admitted that neutrality isn’t realistic.

The library’s collection includes World War II German Nazi material and Frederick Douglass’ Bill of Sale. In the Herskovits Library of African Studies, the largest separate Africana collection in existence, Risseeuw noted that many colonial materials within have “insulting” descriptions.

Despite any personal feelings, Risseeuw said she recognizes that she can’t be the only one to put her judgment on an object and that it has to be part of a larger ethical discussion.

Part of the reason those old books have withstood the test of time is also because of their high quality materials, like good leather and better paper, according to Risseeuw. The tradition of maintenance and repair has also always been inherent to libraries, and therefore many books from the 15th century or earlier are never seen in their original form, Gowler said.

Paper, too, wasn’t always made from trees. Instead, materials with strong, pure fibers — like cotton linens, rags and flax — were used.

When reading ability improved, the Industrial Revolution made it cheaper and faster to produce books with lower quality materials. That was when trees were introduced into paper, adding in an acidic nature that made it prone to deterioration. Better standards emerged in the mid-20th century, and less acidic paper is more commonplace now.

However, that still doesn’t make the books immune to the pests in the library. There are the dermestids that eat proteins, and silverfish, which consume the starch found in paper. There’s also the very tiny book lice, which Risseeuw calls the real-life, romanticized “bookworm.”

Monitoring traps, housekeeping and humidity control have kept bugs at bay. Rather than disposing of them all, Risseeuw, also known as the resident “bug lady,” continues storing and preserving some of the insects in a large, well-documented bug binder, featuring bugs all the way from 2010.

“Someone gave me a house centipede and a roach one time,” she recalls. “Good to have things to put under a microscope for people.”

Despite the risks that come with physical objects, Risseeuw and Gowler agreed that digital materials are far more fragile than paper materials. Gowler noted how, for instance, all the data on the “cloud” is stored on a physical device in a building, where a natural disaster or a power outage could threaten it.

The vulnerabilities of saving everything on the cloud is why Gowler said she recommends printing or storing digital memories within archival boxes in dark and cool places.

To that end, making everything reversible is an important feature of conservation. Russick said plenty of time is spent undoing treatment that past generations have done, like how Gowler took “forever” meticulously peeling tape from a large map.

Half of what they do in conservation is also adding and removing water, Russick said, and new developments are always on the rise to make that easier. One of them includes gellan gum — a transparent, slippery kind of gel that’s made from bacteria and grows on water lily leaves. Because of its ability to retain moisture and be cut into shapes, it can suck stains out without leaving a residue.

At the end of the day, everyone who works in the preservation department said they ensure they keep a meticulous record of what was done with every project.

Seeing how they’ve transformed a piece of time and history is perhaps the most rewarding thing, Russick said.

“It’s just so much fun to see how different it looks,” Russick said. “The worse it looks to begin with, the better it looks after.”

Email: jennawang2024@u.northwestern.edu

X: @jennajwang

Related Stories:

— NU to renovate Deering Library, close it to public for next academic year

— Potawatomi Confederacy Panel Discussion sparks conversation on historic preservation, tribal unity

— City historical organizations celebrate Preservation Month