Chicago’s Symphony Center was bustling on a warm Sunday afternoon, as concertgoers flocked to the illustrious venue to hear celebrated pianist Yefim Bronfman — widely considered a leading interpreter of a vast repertoire — in recital.

The program featured familiar names: Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann. The recital seemed to center around pieces based on Vienna, the “capital of classical music.”

Bronfman opened the concert with Beethoven’s “Sonata No. 7 in D major, Op. 10, No. 3.” In the first movement, he appeared insistent on emphasizing the pulse so much that dynamic markings were sometimes not fully heeded. Sometimes the accompaniment overpowered the main material.

The second movement, marked “mesto” (mournful), was more ponderous than melancholy. At times, Bronfman’s right hand produced a silky tone, giving the effect of fluidity within rhythmic rigidity.

In the pithy third movement, Bronfman wonderfully highlighted the interplay between the pastoral main melody and the boisterous “trio” section. While rushed at times, he had more control over the piano during the fourth and final movement.

Schubert’s “Sonata in A minor, D. 784” was a 180-degree turn away from Beethoven’s sonata. Around the time of composition, Schubert wrote in a letter on his failing health: “I feel myself the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world.”

One of Schubert’s most somber compositions, the piece epitomizes this quote. In the first movement, Bronfman appropriately kept the main melody barren and spaced out. During the violent outbursts, he delivered the most dramatic color changes of his program yet.

The dreamlike main melody in the second movement was played ever so delicately; Bronfman somehow made the ominous, serpentine motif even softer. He again exemplified fluidity within rigidity in the third movement, where disorienting whirlwind-like melodies converged into a furious ending.

After the intermission, Bronfman took the audience 20 years forward with Schumann’s “Arabeske, Op. 18.”

His rendition was soft, yet luminous in the major-key refrain, which was interrupted by two short minor-key interludes, the first painful and the second mischievous. Bronfman did not draw a big contrast in character between these different sections, perhaps in the interest of continuity.

Next came a contemporary piece titled “Sisar” (Finnish for “Sister”) by conductor-composer Esa-Pekka Salonen, which Salonen dedicated to Bronfman. The piece juxtaposed action and stasis, featuring jazzy riff-like passagework.

Bronfman’s journey through Schumann’s five-movement suite, “Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Scenes from Vienna), Op. 26,” was by far the best.

The opening movement, “Allegro,” was more understated than many I’ve heard — a fitting choice, considering the gradual buildup of energy required throughout the five pieces — and brief pushes and pulls of tempo were never overdone. He wasted no time between contrasting sections and again upheld Beethovenian rhythmic strictness.

Bronfman controlled “Romanze,” the delicate second movement of the set, ever so sensitively. His return to rhythmic rigidity in the “Scherzino” permitted the playful, march-like character to shine through.

Continuing without pause, the “Intermezzo” provided a change in atmosphere: a declamatory melody supported by breathless, swirling accompaniment.

The pent-up energy finally burst out in the blazing “Finale.” At times, Bronfman did not hesitate to use notes an octave below what was written to give the piece more volume and grandeur.

The main theme was as exciting as ever; the contrasting second theme, while calmer, still sounded somewhat eager. Meanwhile, Bronfman pushed the speed of the piece to its limits. The suite ended with blisteringly fast chains of notes leading to the last triumphant chords, met with cheers and applause.

Bronfman answered the audience’s call with two encores.

The first was Sergei Rachmaninoff’s menacing “Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5.” The intertwining melodies in the expansive and yearning middle section were once again layered excellently.

The second, Frédéric Chopin’s serene “Nocturne in D-flat Major, Op. 27, No. 2,” where a lone voice sings their heart out atop a shimmering bed of harmony, was the height of sensitivity. The Nocturne provided a warm take-home gift for the audience fresh off a heavy recital.

Bronfman performed a convincing recital overall, in terms of both programming and execution. While the Beethoven left something to be desired, the latter half of the concert exemplified sheer musical ingenuity and mastery.

Email: benkim2026@u.northwestern.edu

Related Stories:

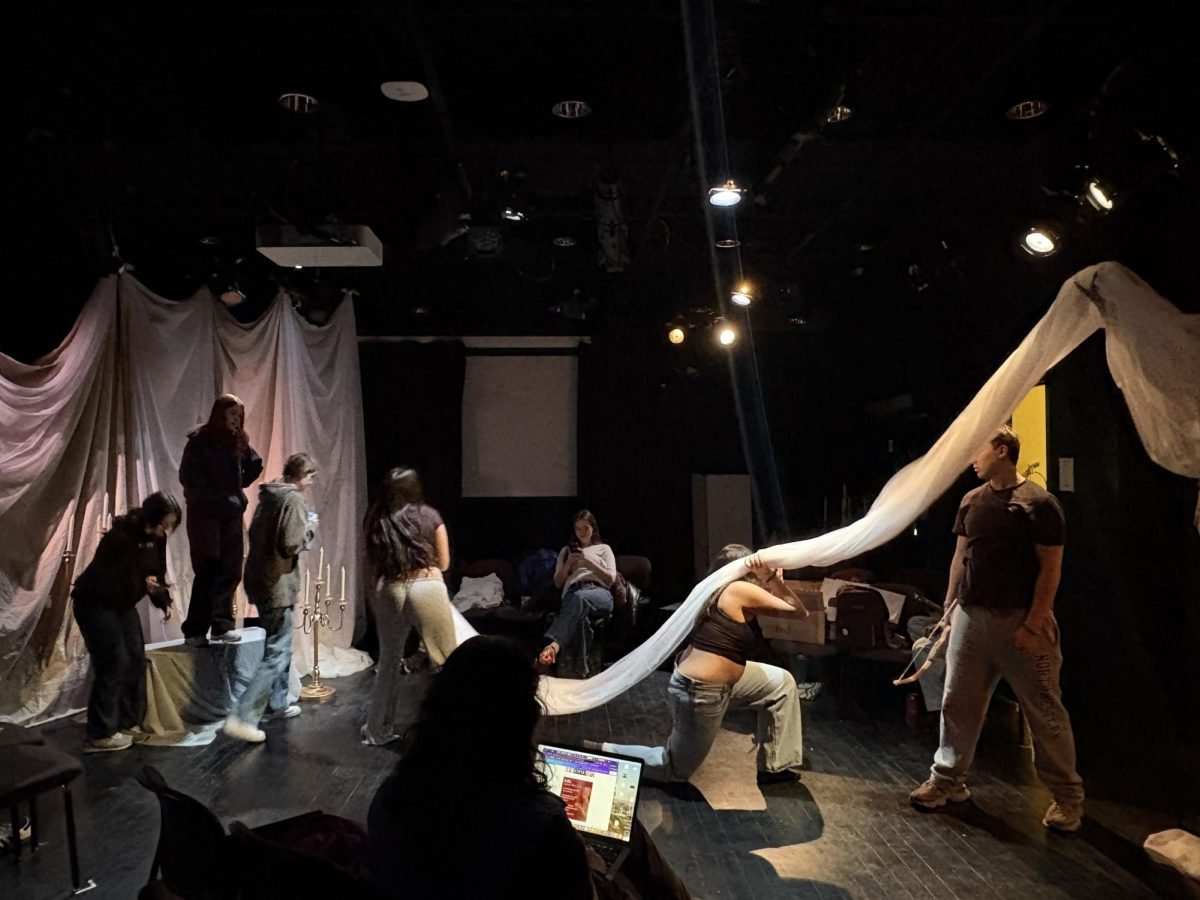

— Cosmia Opera Collective breathes life into opera, uplifts underrepresented composers

— ‘A creative town’: A look inside Evanston’s storied musical history

— Seong Jin Cho and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra dazzle with Mendelssohn, Beethoven, and Kernis