Community leaders host bus tour on Evanston’s Black History

Photo courtesy of Izzy Nielsen

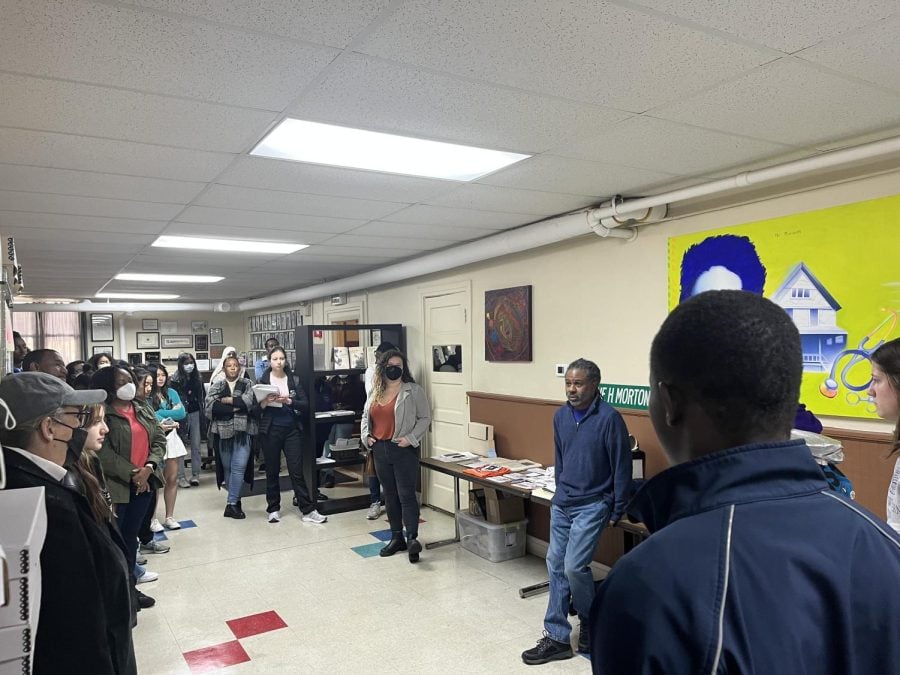

Tour attendees listen to local historian Dino Robinson explain his archival work at the Shorefront Legacy Center.

October 31, 2022

Before the 1960s, when Northwestern did not allow Black students to live on campus, the Emerson Street YMCA provided them with beds. When Evanston Township High School did not permit Black students to use their pool, the YMCA offered them a place to swim. And when Black political scientist and civil rights activist Ralph Bunche conducted research at the University, he lived at the YMCA.

However, the Emerson Street YMCA no longer stands today. It closed in 1969 in an effort to desegregate the town’s two YMCAs. Condominiums now exist in its place.

The former site of the YMCA was one of the highlights in a Saturday tour of Black history in Evanston, led by local historian Dino Robinson and Evanston Community Foundation Director of Community Leadership Karli Butler.

Robinson is the former acting director and founder of the Shorefront Legacy Center, a community-based archive that collects stories of Black history on the North Shore. He said he looks to history to understand the present, and how to combat present issues.

Lack of affordable and accessible housing has been a prominent issue throughout Evanston’s history, Robinson said. Archival work can be a resource for current activists on how to best achieve their goals, he added.

“We’re doing this movement now, (but) has this been done before?” Robinson said. “Who were the players then? What were the issues then? How do they relate to now? How does it inform us now?”

About 30 students, faculty and community members loaded onto the bus for the tour, which drove through central and west Evanston. Attendees learned about prolific residents in Evanston’s Black history, places of importance to the Black community, as well as Black resistance to systemic racism in the city.

The tour highlighted the activism of several Evanston residents, including married couple Drs. Isabella Garnett and Arthur Butler, who opened the Evanston Sanitarium in 1914 as one of only a handful of hospitals in the area that accepted Black patients.

Robinson also said Evanston was a popular destination for pre-eminent Civil Rights activists, including Martin Luther King Jr., who visited thrice in 1958, 1962 and 1963. King advocated for fair housing in the city and delivered sermons, and also spoke at NU. Activist and writer W.E.B. Du Bois visited in 1931 to campaign on behalf of Edwin B. Jourdain, the city’s first Black alderperson.

The history of Evanston is intertwined with Butler’s own family. Butler’s grandparents frequented the Emerson YMCA, she said, attending social events like youth dances.

More than half a century later, her grandfather qualified to receive reparations, but passed away before his lottery number was chosen.

She said learning about the history of the city has affected the way she is raising her 10-year-old son, adding it has historically been harder for Black students to succeed in Evanston public schools. It has also informed her work promoting racial equity through ECF, she added.

“Growing up, I had my grandparents to teach me this history and I’m sharing the same thing with my son, who’s in the Evanston public school system,” Butler said. “I’m purposely positioned to be in this role, just because of the historical context that I bring.”

First-year history graduate student Semiu Adegbenle said he gained a new perspective on the racial history of the U.S. on the tour. As an international student from Nigeria, Adegbenle is studying for the first time at an American school this year.

He said he was surprised to learn about how Evanston codified racism in its laws because he previously thought such explicit policies mostly existed in the South.

The tour also helped him better understand Evanston as a historian, Adegbenle said.

“It shows you that the space itself is like a living organism that is changing and adapting. Sometimes you may be living in a building without knowing that you’re actually in this place that has its own history, its own genealogy,” Adegbenle said. “If we understand space in that way, it also increases our consciousness.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @WiniarskyT

Related stories:

— City historical organizations celebrate Preservation Month

— Shorefront Legacy Center works with NU grad students to record oral history with Black residents

– Community Data Walk shows health and quality of life inequalities in Evanston