For a stretch in his life, Van Donkersgoed was afraid of what tomorrow would bring.

“My life was consumed by pain,” he said. “It was all about how am I going to get through the next day.”

Donkersgoed was held captive by his own body 9 a.m.-3 p.m. every weekday. He would step into a world of what felt like torture, caused by intense migraines.

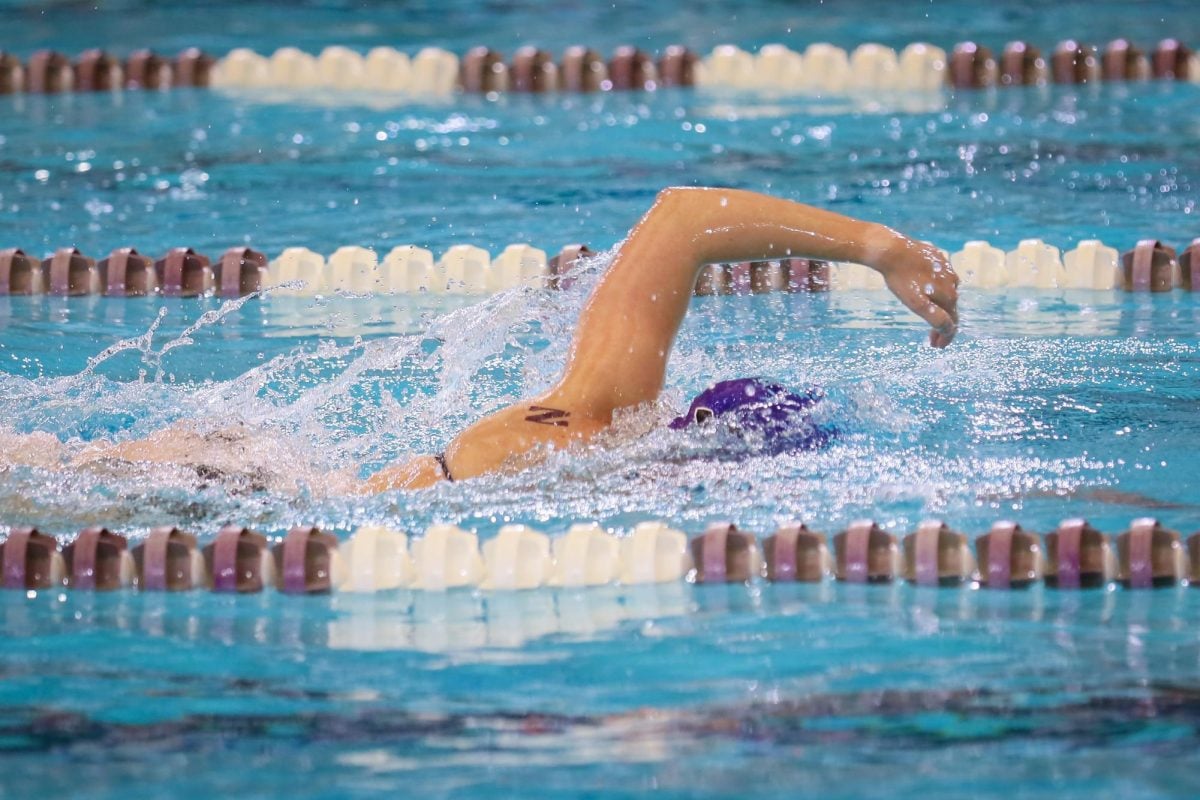

The pool was Donkersgoed’s only savior. He would float there at practice in high school to try and escape the mental imprisonment he felt. But that could only relieve the pain so much. He would lay down on the floor of his club coach’s office with the room completely blacked out.

But for all the darkness that engulfed Donkersgoed’s life at that point, he was able to clutch onto the only thing he could: hope. That’s what lifted him from the vortex of daily debilitating pain to become an integral contributor of an improving Wildcats team.

Donkersgoed’s start in swimming began from a smaller pool than the one he swims in today.

“I was sitting in a hot tub at the health club, and I saw the team that I ended up joining,” Donkersgoed said. “I asked my mom if she could sign me up. I wanted to try it.”

Sue Donkersgoed, Van’s mother, took her then-11-year-old son to meet with Kate Lundsten, the head coach of a club team called the Aquajets. Lundsten was a Division III national champion herself in the 100- and 200-yard backstroke and a coach for USA Swimming. When she saw Van for the first time, she wasn’t exactly sure what to expect.

“My first impression was, ‘Oh my goodness, I wonder if swimming is his sport,’” Lundsten said. “And then we saw his breaststroke and knew he was a breaststroker. I’ve always been surprised by him.”

The young Donkersgoed, who was already a strong student, continued to surprise everyone around him. In his first year, he made the cut to go to the state championship meet. From that meet, he would qualify to go to Zones, a meet of the best swimmers in the Midwest.

“When you see a kid move through the system pretty fast, then you know they are going to do something pretty special,” Lundsten said.

By the time he had turned 14, the budding star had already made the Junior National team, and by 17 he had placed fifth at Junior Nationals in the 100- and 200-yard breaststroke. A slew of triumphs only made him more goal-oriented with one dream above all others.

“Swim Division I,” Donkersgoed said. “All throughout middle school and high school, that was the goal. If everything went to plan and I stayed healthy, it would happen.”

But on a chilly November day in Minnesota in 2009, all his goals and plans changed in an instant.

Just after a workout, Donkersgoed started to feel indescribable pain in his head.

“I had never experienced anything like it,” Donkersgoed recalled. “We were standing around after practice, and I just got sick and didn’t feel well. I remember swimming in high school with the flu, chills and fevers, but this was nothing like that.”

From that moment on, he was thrown into a consistent cycle of migraines that happened only during the week, started at about 9 a.m. and usually went away at the start of swim practice at 3 p.m. Everyday life became a challenge for which he was not prepared.

Desperate for answers, Donkersgoed’s family tried to schedule an appointment at the pediatric neurologist in the Twin Cities, but there was no available appointment until June. With such crippling headaches, Van couldn’t last until then.

The breaking point came on a day when Donkersgoed’s pain was so intense, his mother yanked him out of school and rushed him to a hospital emergency room. There, he immediately received a spinal tap, IV fluids and a full dose of morphine, though there was still no definitive answer on what was wrong with him. The next day a pediatric neurologist was able to look at Donkersgoed and diagnosed him with vascular and muscular minor headaches. The doctor prescribed loads of medication, such as Beta blockers, anti-depressants and anti-migraine pills, and sent Donkersgoed on his way.

Time passed and much to Donkersgoed and his family’s disappointment, the medication wasn’t working.

“Two weeks, three weeks go by and I see (the doctor) for a follow up and he asks how I’m doing,” Donkersgoed said. “I’d tell him I wasn’t any better and he’d say, ‘Well, let’s throw some more pills at you.’”

The pattern continued with this doctor. When pills wouldn’t work, he would either switch medication or add on more. What the doctor didn’t realize was that he was only making Donkersgoed worse.

“The medication I was taking caused rebound headaches,” he said. “What I was doing was trying to treat something that created another one.”

It was especially hard on Donkersgoed’s mother watching the boy she raised, who went to kindergarten every day in a suit, tie and black dress shoes by his own choice, go on mood swings daily.

“He was struggling,” Sue Donkersgoed said. “It’s not fun to see your child struggling.”

Van Donkersgoed went on to miss about 150 class periods because of his migraines. His classmates could have sworn he was an old man because the pain would not allow him to keep his head above his shoulders.

“I literally breathed away migraines everyday,” Donkersgoed said. “The pills never once worked. It felt like everything was collapsing around me and my life was falling out from underneath me. ”

Although the water helped with the migraines, he was still not able to train at the rate to which he was accustomed. There were moments where he was off his best times by 6 to 8 seconds, an eternity for a swimmer.

“It was disheartening,” Donkersgoed said. “You feel betrayed by your own body and by medicine. Everyone around you just wants you to get better.”

Quitting suddenly became a regular thought as he floated lifelessly in the pool before practice.

“It would’ve been the easy way out,” Donkersgoed said. “I even thought about dropping out of school. If there was one thing you knew you could count on every day, it was pain.”

In November 2010, Donkersgoed’s fortune finally changed. He went to the Mayo Clinic to try and get another opinion on what was going on inside his head. The doctors there took one look at his MRI and within seconds pointed to what he recalls as “this big golf ball size thing” and diagnosed him with a deep sinus infection.

“It was an answer,” Van said. “It was something we knew that could be a different treatment course. We knew that we couldn’t go on the same treatment course with no relief.”

Then came the miracle. Donkersgoed went home, took an antibiotic and suddenly became migraine-free. But he wasn’t out of the woods yet.

“The damage was done,” Donkersgoed said. “I had been on those medications daily, which they had suggested I take only about every three or four weeks. At that point, it looked great but you can’t just pick up right where you left off.”

Time was ticking for Donkersgoed because on July 1, 2011, college coaches were finally allowed to get in contact with recruits. He wasn’t sure how many calls he would get.

But he had lucked out because in August 2010, in the middle of all his struggles, Donkersgoed had one week of swimming when he posted some of his best times at a crucial meet. When July 1 came along, he was pleasantly surprised to receive about 18 calls.

But one of them wasn’t from Northwestern.

“I thought he was a junior-to-be and not a senior-to-be,” NU coach Jarod Schroeder said. “Once I found out he was a senior, he was on our radar.”

Schroeder didn’t care about the migraines and their potential effect on Donkersgoed in the future. He just loved Donkersgoed’s character.

“I was really impressed with the kid he was and what the coach was telling me about his work ethic,” Schroeder said. “He’s somebody who is moldable and somebody who is going to listen to the coaches. That’s the kind of guy I want on my team.”

Schroeder was one of the first to go up to Minneapolis and visit Donkersgoed. But the Eden Prairie, Minn., native was already sold on NU when seniors Varun Shivakumar and Alex Ratajczyk came up to him at that sectionals meet where he performed so poorly and started talking with him.

Schroeder knew the migraines could return at any time. Even Donkersgoed himself wondered if NU’s team, the smallest in the Big Ten, should take a chance on him. When Donkersgoed finally turned 18, he told his mother there was only one thing in the world he wanted for his birthday.

“He goes, ‘I just want to commit to Northwestern,’” Sue Donkergoed said.

After sinking to his lowest point physically and emotionally, Donkersgoed could now check off his number-one long-term goal and become a new member of the Wildcats.

Donkersgoed’s college career struggled at the start partly because he believed the medication he took back in high school was still in the process of leaving his body. He has experienced only one headache since coming to NU and he has been able to avoid the dreaded migraine cycle. The doctors at NU have him taking a very low dose of an anti-depressant every night to make sure that the pain doesn’t return.

He finished his freshman campaign with a bang at the Big Ten Championships, where he recorded the third-fastest time in NU history in the 200-yard breaststroke. It’s a time that Donkersgoed admitted the “old him” would make, and he believes it can only get better.

“I don’t have anything further to lose in swimming,” Donkersgoed said. “I’ve lost it all. I’ve been to the bottom. In my collegiate career, I only have places to go and room to grow.”