In Focus: Amherst account inspires Northwestern student to reveal own sexual assault

November 27, 2012

Earlier this quarter, an Amherst College student garnered national attention for her account of callous treatment by school administrators following her rape. For one Northwestern student, the story was all too familiar.

“I battle my memories of the rape every day,” Weinberg senior Lauren Buxbaum wrote in a Facebook status posted Oct. 18. “It consumes me in a way I hope none of you ever experience. The only thing that was holding me together was my life here at Northwestern. And now that has been taken away, and I don’t even have the energy to battle for my life back.”

Like former Amherst junior Angie Epifano, Buxbaum was raped. Like Epifano, Buxbaum was transported by campus police to the hospital and admitted to a psychiatric ward after she expressed difficulty dealing with the assault.

“It was seriously like reading my story,” Buxbaum said of the Amherst account.

But unlike Epifano, Buxbaum said she felt pressured by the administration to go on medical leave until she was “healthy” enough to return to NU.

Buxbaum’s story exposes the harsh realities of policies that attempt to balance the safety of individual students with that of the broader NU community. Despite new resources and policy amendments, NU’s response to sexual assault still has its flaws.

“Things need to change here too,” Buxbaum ended her post. “Don’t forget it.”

Losing control

Buxbaum said she was assaulted off-campus in late July while walking home from a friend’s apartment in the early morning. Her attacker was an Evanston resident she had seen before but did not personally know.

University Police reports indicate officers took Buxbaum to NorthShore Evanston Hospital almost immediately after her assault. Buxbaum said she decided not to press charges because she did not want to relive the traumatic experience.

The next month, Buxbaum discovered she was pregnant. She had an abortion two days later.

When fall classes began, Buxbaum told friends, family and a few close professors what happened but struggled with depression.

In early October, she broke down. In an email to a professor, Buxbaum described feeling hopeless and not wanting to live anymore because of the assault.

The professor called Buxbaum repeatedly, but because Buxbaum had lost her phone, she said she could not answer to explain that she was not suicidal.

“Anyone who’s been raped will tell you you just don’t want to keep going,” Buxbaum said. “It’s not that you want to die. It’s that you just wish that you could crawl in bed all day.”

Police reports confirm UP arrived at Buxbaum’s apartment just after 9 a.m. Oct. 6. Because police officers are unqualified to make psychological assessments, they transported Buxbaum to the hospital for evaluation.

Buxbaum said the hospital triggered memories of the assault.

“I probably looked insane,” she said. “But I wasn’t insane.”

Buxbaum spent the next four days in the psychiatric ward, according to medical records.

Two days into treatment, Buxbaum received a letter from the dean’s office outlining the conditions for returning to NU.

The letter stated if Buxbaum did not sign medical releases, she “would not be allowed to return to Northwestern University.” It also said if she was not deemed “healthy and safe enough,” officials would “work with (her) to take a medical leave of absence.”

Assistant Dean of Students Betsi Burns, who signed the letter, declined multiple requests for comment.

After being discharged Oct. 9, Buxbaum discussed her next steps with NU’s Counseling and Psychological Services and the dean’s office. Documents obtained by The Daily show her medical withdrawal was processed by Oct. 15.

An ‘impersonal’ system

Buxbaum and Epifano’s stories have sparked discussions across campus about NU’s sexual assault and mental health resources.

Although CAPS and other outlets treat mental health issues, some students do not always find them helpful.

Multiple students said their experiences with CAPS were distant. Buxbaum referred to CAPS as a “disconnected and impersonal” bureaucracy that should be more “sympathetic.”

Weinberg senior Katie Wells agreed that CAPS can seem removed from students.

Wells withdrew from two classes during her freshman year because of depression. She decided to fully withdraw from classes, a process that typically lasts two quarters, during her junior year. However, the University told her she would have to leave for an entire year because it was considered her second withdrawal for psychological reasons, she said.

Although medical leave was the right decision for Wells, she said petitioning to come back early and re-enrolling was difficult. She had trouble contacting Student Affairs, which conducts initial conversations with returning students, and when she finally did, she said administrators did not fully understand her situation.

“I just felt like they weren’t really willing to hear what I had to say about whether it was a good idea for me to come back,” Wells said. “It was difficult to sit down with them and have an in-depth discussion.”

Other students simply find getting on CAPS’ radar challenging.

McCormick sophomore Kate Matias began struggling with depression last year. Extremely uncomfortable with CAPS’ required phone evaluation, it took her weeks to set up an appointment.

CAPS always has a counselor on call for emergencies, but Matias said she wishes there were open hours for students who just want to talk to someone.

Shaina Coogan, spokeswoman for the mental health student group NU Active Minds, said many of the perceived faults with CAPS stem from the service’s lack of funds, manpower and publicity. It is also difficult to individually serve 8,000 students, she said.

“They don’t have all of the resources that maybe they should,” the Weinberg senior said. “But I guess something that students also have to consider is that CAPS was never meant to be everybody’s personal therapist office.”

Taking a break

CAPS and University officials say medical leave is a voluntary choice made by the student. Although administrators can make strong recommendations, NU cannot force students to take medical leave.

“The fact of the matter is that it is ultimately the decision of the student,” said Patricia Telles-Irvin, vice president for student affairs.

However, Buxbaum said that decision may not be “as clear-cut as they make it seem.”

Medical leave was first suggested to Buxbaum in the letter she received from the dean’s office while in the hospital.

CAPS assistant director David Shor, who was referenced in the letter, said these types of notices are meant to clearly outline necessary steps so students can smoothly transition back to school.

However, Buxbaum said the letter’s timing and wording confused her, calling it a “school death sentence.” When Buxbaum discussed medical leave with officials, she said she felt like the decision had already been made for her.

Medical leaves for psychological reasons last a minimum of two quarters, so Spring Quarter is the earliest Buxbaum can return to NU.

Coogan, a former Daily staffer, said it presents difficult choice for both sides when students feel pressured into going on medical leave.

“It comes down to the University not wanting to be liable for something really bad happening,” she said. “In that, I think they are trying to protect their students, but it’s really hard to have one of those one-size-fits-all policies.”

Students and administrators alike recognize the institutional deficiencies that leave students with less-than-ideal options after hospitalization. Some students can continue classes with counseling or a reduced course load, but NU’s rapid quarter system and the time consumed by hospitalizations can compound problems for students who are already behind.

Although officials may view poor academic performance as indicating a student cannot function, for Buxbaum, who maintained a 4.0 grade point average before the assault, the structure of attending classes mattered more than earning good grades.

“Who cares if you get a C if it’s getting you out of bed?” she said.

Laura Stuart, NU’s sexual health education and violence prevention coordinator, said the process can seem unfair to survivors. Some say medical leave can further isolate victims, but Stuart acknowledged that because trauma truly can make it hard to cope, taking time off can be helpful.

“Someone took away your control and violated your boundaries,” she said. “Now that has an impact on your life that might make it difficult for you to function. That sucks. It sucks. People have a right to be mad about that.”

Buxbaum said being confined to the psych ward and medical leave turned her whole life upside down.

“They took an already traumatized person and just made it exponentially worse,” she said. “And then told me it was my choice whether to go on medical leave or not. But you’ve made it so that I am a broken person now.”

A more sensitive response

Buxbaum is not the only rape victim who has failed to connect with CAPS.

Alumna Cassy Byrne (Weinberg ’12) experienced a series of abusive relationships during her time at NU, including one with a graduate student that triggered an eating disorder during her freshman year.

Byrne said it took her years to realize her relationships were unhealthy and to approach CAPS for counseling. When she did, officials instead referred her to the Women’s Center’s more specialized services.

Although CAPS was not very involved in Byrne’s recovery, she appreciated when CAPS shared notes on her case with the Women’s Center. Small details that take the burden off the victim can go a long way, she said.

“The thing we really need is compassion — and not forms,” Byrne said. “It just shouldn’t be the victim’s responsibility to take care of everything. What they’re doing is reaching for help because they can’t deal already.”

Byrne said educating others about the psychological effects of sexual abuse should be a major priority for NU.

There is a difference between victims wanting to die and not wanting to live with their current pain, she said.

“What would really help in those situations would be for everyone in an administrative position to be educated and informed about sexual assault and how it affects people,” Byrne said. “You need to sensitize everyone that works in a position of authority.”

A breakdown in communication

According to CAPS and UP officials, emergency measures must be taken once they believe a student is in danger.

“Safety is our first concern,” Shor said. “We don’t want to take risks with people’s safety.”

Aside from letters, the University does not usually interact with students during hospitalizations to avoid interfering with external treatment, Shor said.

However, these procedures caused NU to misinterpret Buxbaum’s situation, Buxbaum said. From the time Buxbaum sent the email until her hospital release, she did not have any face-to-face interactions with NU officials. There was no opportunity for her to explain that she had not intended to kill herself, she said.

Some view the University’s precautions as extreme and premature.

In a statement released to The Daily, Buxbaum’s parents said NU acted more in its own interests than their daughter’s when police transported her to the hospital for psychological evaluation.

“It was an overreaction by the University,” said Nancy Buxbaum, Lauren’s mother. “Counseling would have been a first step. Getting some background after this would have been a first step.”

Both Buxbaum and her parents questioned why no attempt was made to contact her family members, who live about a half hour from NU in Arlington Heights, Ill., until after she was taken to the hospital. Because Buxbaum is an adult, her parents were also not involved in conversations regarding medical leave. Buxbaum added that NU could have contacted her roommate.

Rather than help her recovery, Buxbaum said, NU just made things worse.

“It was just confusing and scary and it took what was already traumatic and made it even more so,” she said.

Steps in the right direction

Reported inconsistencies in NU’s response to sexual assault fall on a backdrop of recent attempts to improve the same efforts.

After a student complaint to the U.S. Office for Civil Rights, NU amended its Sexual Assault Hearing and Appeals System to clarify the time frame for completing complaints and how to report concerns about pending SAHAS proceedings, said Thomas Cline, NU’s vice president of general counsel, in an email to The Daily.

NU’s Student Handbook indicates that the Sexual Assault policy is currently being reviewed and could be revised before the end of the academic year.

The most significant change came last fall with the establishment of the Center for Awareness, Response and Education, NU’s first centralized resource for victims of sexual violence.

CARE is primarily a confidential advocate for sexual assault survivors. Previously victims could seek help from numerous campus resources, but now the center is working to make “all signs point to CARE,” said Eva Ball, NU’s first sexual violence response services coordinator.

CARE is also focusing on education, as Ball is developing a “bystander prevention protocol” to train students and staff about how to react when someone discloses an assault.

“It’s really essential when we’re dealing with people who have been victims of sexual violence that they’re in control, that they’re making decisions for themselves,” she said.

But CARE can be minimally involved in cases like Buxbaum’s, which involved both sexual assault and safety risks. UP Deputy Chief Dan McAleer said counselors do not accompany officers on wellness checks because suicidal individuals pose a risk to others.

Consequently, Buxbaum did not meet with CARE until after her hospitalization. She said she would have preferred the center to be involved sooner.

“There should be people like that who are the first wave of contact,” Buxbaum said. “Not scary people in uniforms, coming to tell you that you have to go somewhere.”

Confronting a tough reality

Nearly two months after her psychiatric stay, Buxbaum is still struggling with the consequences of medical leave.

Because individuals on medical leave are not active students, they no longer qualify for federal financial aid. Buxbaum works five different babysitting jobs in addition to her job at Pick-Staiger Concert Hall — one of her few points of contact with NU — to pay for her Evanston apartment.

Buxbaum will not be able to write her senior thesis with other American studies majors she has known for the past three years, and without an undergraduate degree, she can no longer attend graduate school next year at Yale University, where she was offered a position.

“I feel like a loser, like an outcast,” Buxbaum said. “Like I’m not supposed to be here, that I did something wrong. That because it’s going to take me five years to graduate, that I’m a failure.”

Buxbaum said she has not yet decided when — or if — she will return to NU.

Though she said she misses her friends and classes, at this point she is unsure about the re-enrollment process.

“Are they going to be mad when they find out that I am so upset with the way that they treated me?” Buxbaum asked. “Will they put up more hurdles or not believe me, that this happened?”

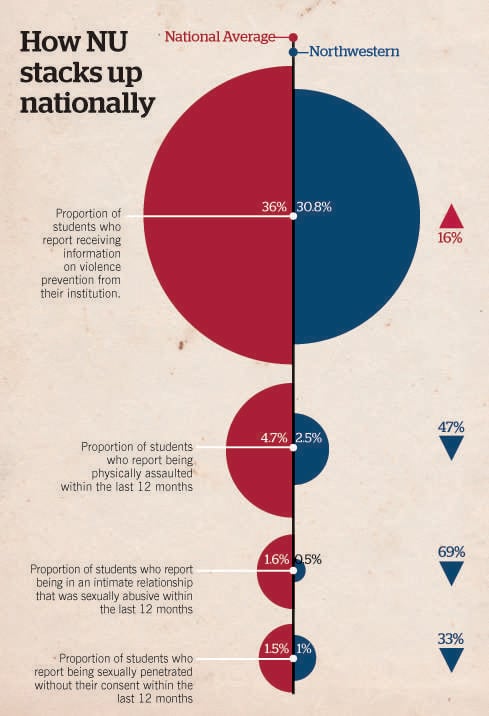

View a larger version of the info graphic above this story.