Northwestern students tour Chicago Torture Justice Center, learning the history of police torture in Chicago

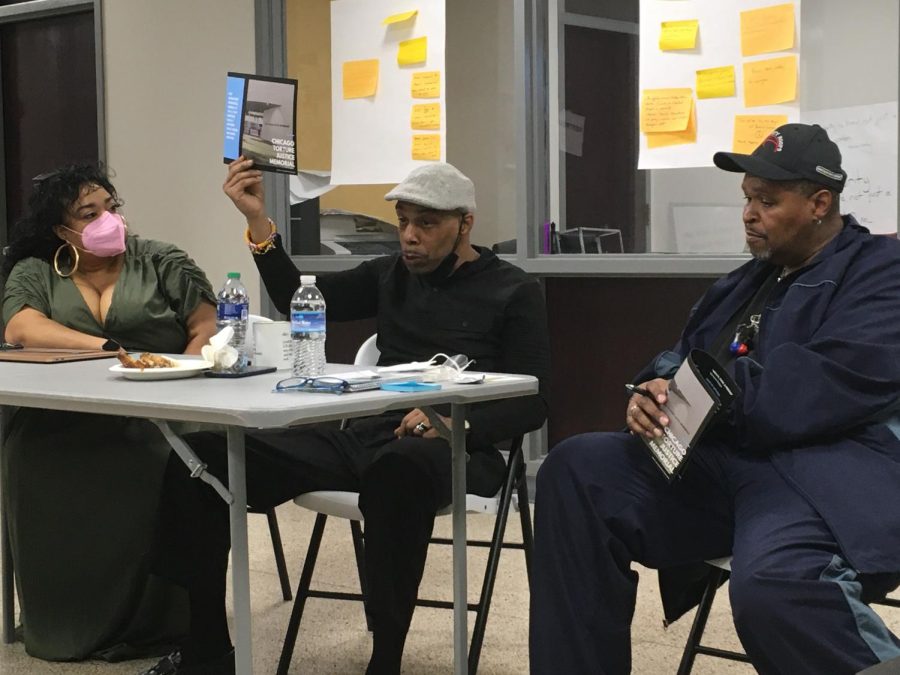

Aislinn Pulley, Mark Clements and Gregory Banks, left to right respectively, during the panel discussion.

April 9, 2023

Content warning: This article contains mentions of torture and police violence.

About 15 Northwestern undergraduate and graduate students traveled to the Chicago Torture Justice Center to learn about the city’s history of police torture Saturday on a trip organized by One Book One Northwestern.

CTJC was created in 2015 after the Chicago City Council passed the Reparations Ordinance, granting reparations to torture survivors of Jon Burge, a former Chicago police commander who tortured predominantly Black defendants to obtain false confessions in the ’70s and ’80s. The package funded the CTJC, public school education on torture, $5.5 million in financial compensation and free access to Chicago city college education for survivors and their families, among other initiatives.

CTJC co-Executive Director Aislinn Pulley said the ordinance resulted from a three decade long fight led by survivors, their families, activists, attorneys, artists and scholars. The center practices politicized healing, which she said focuses on grieving through political action.

“It’s healing to organize,” Pulley said. “Dismantling these systems that continue to incarcerate our people and continue to murder our people and torture people is healing.”

Pulley said Burge received a promotion within the police department due to his historic numbers of closed cases. She said his rise mirrored the politics of the country at the time: Reaganism, the demonization of the Black working class and the war on drugs contributed to the carceral state.

CTJC Safety Coordinator Gregory Banks and CTJC community organizer Mark Clements presented at the event. Both are Chicago police torture survivors.

A Cook County judge sentenced a 16-year-old Clements to a life sentence without parole in 1981, using a false confession he gave after being tortured. He spent 28 years in prison.

Clements added the fight for reparations is not over.

“We have over 100 of Burge’s victims still inside of the prisons, as well (as victims of) disciples of Burge,” Clements. “Well into three to four hundred of those people are languishing behind prison walls.”

Banks shared his story of being tortured in the middle of the night in the Chicago Area 2 police station as a 20-year-old. He said the police beat him with a flashlight, held a gun to his mouth and suffocated him with a plastic bag.

It took four days for him to receive medical attention from a doctor.

“Every time I talk about my story, it’s really emotional,” Banks said. “Burge was a monster.”

Banks said politicized grief has made talking about his experience easier because it allows him to channel his energy.

Event facilitator Patricia Nguyen, former NU Asian American studies professor and current American studies professor at the University of Virginia, is designing the CTJ Memorial, the last part of the ordinance that has not been fulfilled. She said she’s hopeful Chicago Mayor-elect Brandon Johnson will fund the project.

“If we had private money, this would have been built. But we want to hold the city accountable,” Nguyen said. “The city cannot pretend like this history never happened.”

The memorial design is a spiral that displays a timeline of historical events, leading to a community center at the end. The survivors’ names will be on the walls, along with space for future names to be added.

SESP senior Alyssa Coughlin attended the event because of their interest in policing and prison abolition. Despite growing up right outside of Chicago, they didn’t learn about Burge in high school.

Coughlin said they research police violence, but the academic world often cuts out the voices of those affected by an issue. They added that the conversation about politicized healing especially stood out to her.

“It’s lovely they’re providing these services to people for free without any stipulations and will not abandon these people,” Coughlin said. “We are so willing to abandon people once we’ve decided that they’re bad, and that’s never going to make the world a better place.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @KristenAxtman1

Related Stories:

— NU profs. and criminal justice researcher discuss juvenile justice reform

— Law School program aims to help young people transitioning from juvenile justice system