From civil rights attorney to prosecutor: Laura Coates discusses advocacy in the courtroom

Laura Coates discussed her new memoir on working as a prosecutor.

February 1, 2022

When former federal prosecutor Laura Coates learned the victim of her car theft case was an illegal immigrant, she said she didn’t know what to do. Some colleagues advised her to warn him. Others cautioned against it, saying she could face disbarment.

Legally, Coates said she had to report him. But morally, she didn’t think it was right that this man had to risk deportation by reporting the crime.

“I felt powerless with all the power I had,” she said.

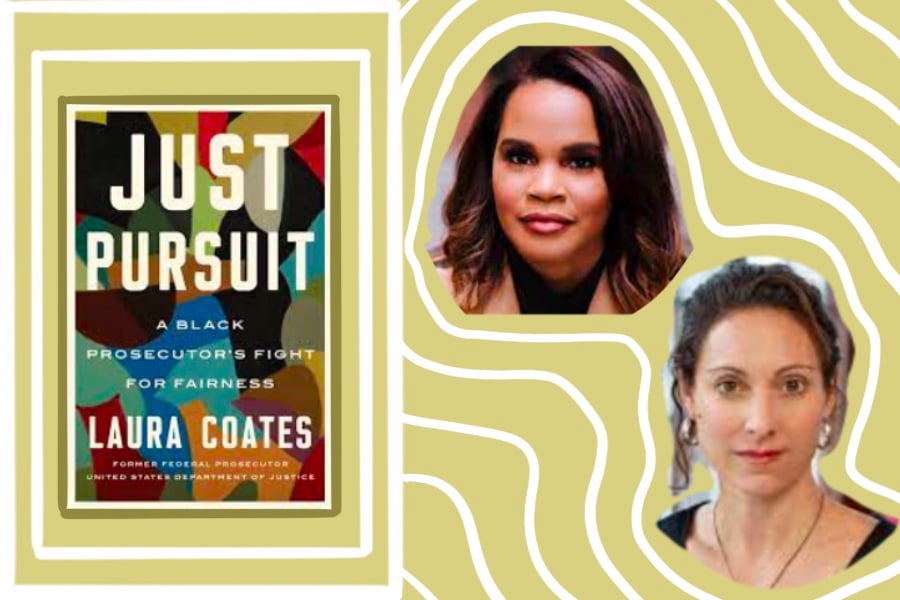

This dilemma illustrates a theme in Coates’ new book: “the pursuit of justice can create injustice.” Now a legal analyst at CNN, Coates discussed her memoir, “Just Pursuit: A Black Prosecutor’s Fight for Fairness,” with New York Times Magazine writer Emily Bazelon at a Monday event hosted by Family Action Network and co-sponsored by SESP. The memoir details Coates’ experience as a Black woman trying to make a difference as a prosecutor.

Before becoming a prosecutor, Coates worked as a civil rights attorney for the Department of Justice, specializing in the enforcement of voting rights, according to FAN executive director Lonnie Stonitsch.

“She traveled throughout the nation supervising local and national elections and led investigations into allegations of unconstitutional voting practices,” Stonitsch said.

As a civil rights attorney, Coates said she was automatically labeled a champion of marginalized people. Shifting to prosecution was a “seismic shift,” she said. On the other side of the courtroom, she said she had to choose her moments for advocacy.

Coates said she had to make cost-benefit analyses when making recommendations for sentences. She had to think about the necessary amount of lenience or severity for the majority of her cases to establish credibility before a judge. She said she had to be careful with how much she deviated from the norm and had to choose those cases carefully.

“So when you actually ask for it, when you’re sitting and acting as an advocate, does the judge look at this as enough of an aberration that they take notice, or a continuation where they look and perceive you as sort of the Trojan horse of prosecutors?” Coates said.

She and Blazeon also discussed the merits of incarceration as a consequence for crimes. Coates said she could provide better tools for redemption with drug court cases, offering programs instead of prison time. While there’s data for prosecutors to see how drug court sentences affected recidivism, Blazeon said this same evaluation should exist for incarceration.

“I would argue that one of the measures of success of a system is whether it’s helping to keep people out of jail and prison and help make them more productive citizens, or at least not get in their way,” Blazeon said.

According to Coates, prosecutors have so many cases on their desks that they don’t have time to methodically work through each one and decide on the best outcome for each individual. They end up devoting the most time and resources to the big cases.

She said as a society, people should evaluate the purposes of the prison system, whether it’s about retribution, rehabilitation or preventing recidivism. But it’s hard to investigate this as a prosecutor.

“Oftentimes, inertia keeps everything in motion, even when our better selves know it should be revised,” Coates said.

While she didn’t perform the same amount of advocacy as an attorney, Coates said prosecutors need to be proponents of civil rights. With prosecutors having so much discretion, they need to be aware of racial bias.

Moreover, she said people of color should be in positions of power.

“I want to disrupt this fallacy that Black and brown people in particular only should occupy one space in a criminal courtroom and that is of the defendant,” she said.

Email: emmarosenbaum2024@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @EmmaCRosenbaum

Related Stories:

— NU is behind on Indigenous initiatives and enrollment, panel says

— Dr. Wendy Greene discusses the intersection between natural hair, civil rights