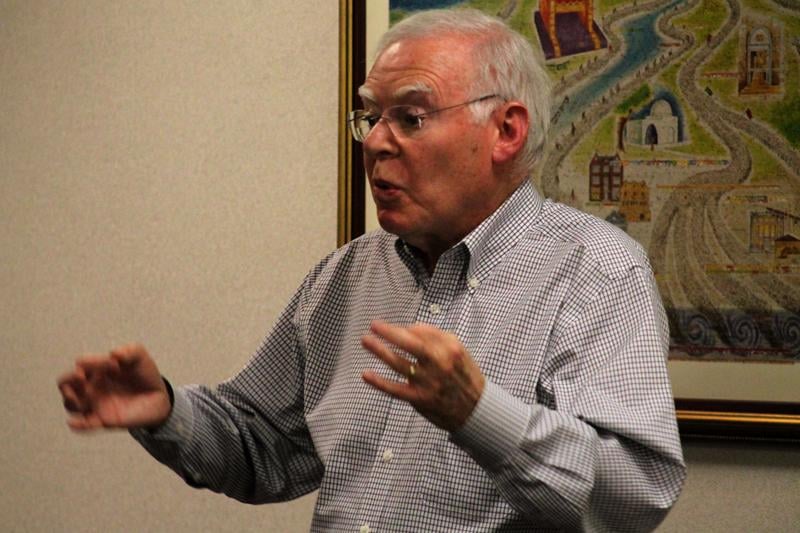

Holocaust survivor Ralph Rehbock, the vice president of the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, speaks frequently about the events that occurred after 1940. Monday night at Northwestern, however, he shared a different tale.

“We all know the end of the story,” Rehbock (McCormick ’57) said. “What happened after 1942 with the camps, the executions, the gas chambers. But that’s not the story I’m going to tell.”

Rehbock spoke to an audience of about 50 at the Tannenbaum Chabad House about his experiences as a survivor of the Holocaust and Kristallnacht. This month marks the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht, when Nazi forces destroyed thousands of Jewish-owned businesses, buildings and synagogues in Germany and parts of Austria on Nov. 9 and 10 in 1938.

Rehbock began his story by detailing the events leading up to Kristallnacht, translated as the “Night of Broken Glass,” and emphasized that unlike most Holocaust survivors, he was not going to only tell what happened in the late 1930s and early 1940s in Nazi Germany.

“Many survivors start their stories with 1942, when there was a knock on their door,” he said. “If I tell any story at all, it’s how the Holocaust was allowed to happen.”

Rehbock began his story nearly two decades earlier, in 1923. World War I had ended five years earlier, and the country was in a state of distress. They had lost the war, inflation had skyrocketed and a depression was looming. That, he said, was when the politicians came along. He recalled close to 30 different political parties, among them the National Socialist German Workers’ Party.

“The Nazis took a different slant,” he said. “They said we must blame those people within our country that caused these bad things: the Jews.”

The propaganda began slowly. Signs were plastered on every street corner, bearing anti-Semitic slogans. Lies were spread, Jews were beaten and Hitler continued to gain power. The Nuremberg Laws were put into effect, denying Jews basic rights including owning a passport and getting married in a synagogue.

After a while, Rehbock said, his parents decided they needed to find a way to America. In 1938, when Rehbock was 4 years old, they made an appointment at the American embassy in Berlin to try to obtain a visa. Their appointment was for Nov. 10. The evening of Nov. 9, Rehbock recalled, he looked out of the hotel room window to see a synagogue down the street burning, and little did he know that the synagogue in his hometown of Gotha, Germany was being incinerated as well. The family had hired a teenage girl to watch the house, and they later learned that Nazi thugs had come to their house that night, demanding to speak to Rehbock’s father. The girl feigned ignorance, which prevented the father from being among the 30,000 men arrested and shipped off to concentration camps that night.

After receiving their visas to leave the country, the Rehbock family departed for America, with Rehbock’s father first flying to England. Rehbock and his mother got on a train to Holland and eventually successfully reached America by boat, where Rehbock said he “happily observed the Statue of Liberty.”

Throughout his story, Rehbock stressed that it could well have had a different outcome if not for the kindness and compassion of strangers.

“Think that there are good people, and people do good things, and we should learn the lesson to do the right thing,” he said. “All the events that took place might’ve ended up with a different ending if some people had paid attention.”

Weinberg senior Martin Amesquita, a member of the Chabad executive board who helped plan the event, said the group chose the speaker because “we wanted someone to discuss their own personal story.”

“History isn’t a series of events that you memorize,” Amesquita said. “It’s stories that happen to real people.”

Rabbi Dov Hillel Klein, leader of the Chabad House, recognized the importance of having a speaker with personal knowledge of the Holocaust, which he said is “part of our Jewish identity.” As Holocaust survivors become older, he said, being able to interact with them becomes even more important, for not only the Jewish community, but also the world as a whole.

“It teaches us unbelievable lessons on how to behave, how to stand up for each other, how to treat each other,” Klein said. “Do we stand up for what’s right when we’re put to the test?”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @oliviaexstrum