When Nathan Eddy (Medill ’06) started working on a short documentary about the old Prentice Women’s Hospital more than a year ago, he knew he was not dealing with the most attractive subject.

“It’s not a beautiful building in the traditional definition of beauty,” he said.

But he also knew the hospital had a cherished place in the architectural history of Chicago. Designed by revered Chicago architect Bertrand Goldberg, the cloverleaf-shaped tower aimed to revolutionize maternity treatment when it opened in 1975.

Nearly four decades later, Northwestern is moving ahead with its controversial plan to demolish the building and replace it with a biomedical research facility.

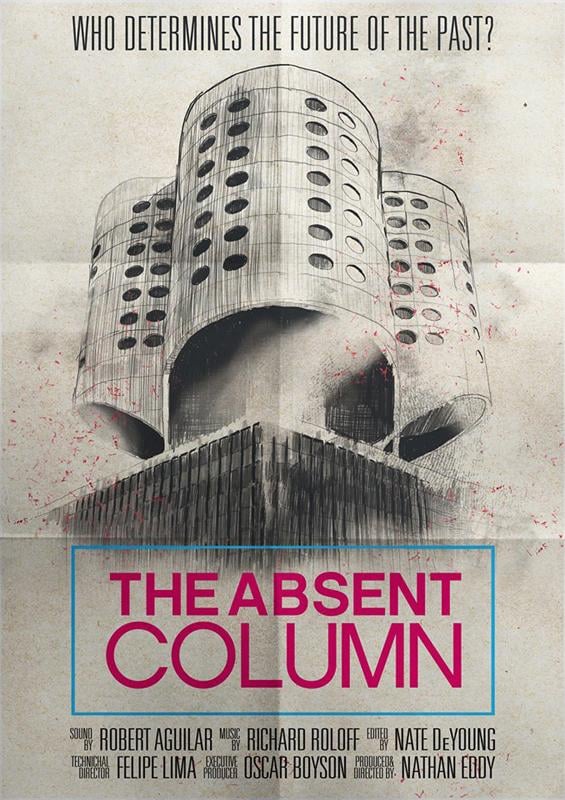

Eddy recruited three other NU graduates to chronicle the contentious lead-up to the demolition, as well as Prentice’s own roots in Chicago’s architecture community. Titled “The Absent Column,” the eight-minute documentary features several interviews with Chicago preservationists, architecture critics and University spokesman Al Cubbage, who says NU has “agreed to disagree” with its opponents on the issue. The movie premiered this summer at the Durban International Film Festival in South Africa and since then has screened at the Architectuur Film Festival Rotterdam in the Netherlands and the Architecture and Design Film Festival in New York.

On Wednesday afternoon, Eddy spoke with The Daily about his inspiration for the documentary, the filmmaking process and Prentice’s legacy.

On how Prentice fit into Chicago’s storied history of architecture: “As somebody who spends a lot of time reading about Chicago architecture and Chicago’s place in the history of the development of modern architecture, it was very important to me to get that across to people to say, ‘This may not be a stunner in the typical way that we use that term, but it’s incredibly important and it’s not only an incredibly poignant example of how Chicago was really at the forefront of architecture, but also of engineering and of how architecture can influence society for the better, which was something that Bertrand Goldberg was very interested in.'”

On the goal of the documentary: “I wanted to make a film where you could empathize with the building and you could humanize the building, which is something that’s difficult to do, even for something like the Wrigley Building. To do that for Prentice, my God. ‘Here, go on a date with this building.’ Oof. That’s asking a lot from people.”

On working with Geoff Goldberg, Bertrand Golberg’s son: “He and I just poured over documents, and I went through the Northwestern University library archives, going through every article that had been written about it … It was daunting. You could have made a 90-minute documentary just on how this building was made, but the architect’s son said something that really stuck with me on our first meeting. … He was telling me that his father would be much more interested in a film that explored what the built environment does for society than a very technical piece on, well, this is how they poured the concrete, here’s the computer program they use to design it.”

On asking Northwestern to participate in the documentary: “I told (Cubbage), ‘Look, we want to make a film about this process,’ and I’m not going to come in to this office and put you in a corner and say, ‘Why are you tearing down this beautiful building?’ And he took me at my word and gave me the benefit of the doubt.”

On what he learned about Prentice as he made the film: “If you really want to change somebody’s mind on this, it’s incredibly difficult. Those people do professionally what I just am trying to do for the first time, which is draw attention to our built environment and for the wider community … to take a closer look at what’s happening to their surroundings because it’s very easy to ignore that.”

Email: patricksvitek2014@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @PatrickSvitek