We’ll never know exactly what happened to Harsha Maddula.

The McCormick sophomore’s disappearance from an off-campus party Sept. 22 stunned a community returning to campus for a new school year. Evanston police concluded their investigation into Maddula’s death last week, determining alcohol played at least a contributing role.

Cmdr. Jay Parrott, EPD’s spokesman, said the death was “accidental in nature with … a contributing factor of alcohol,” citing a urinalysis test and data from the Cook County medical examiner’s office indicating Maddula’s blood alcohol level was about 0.12 at the time of his drowning.

What made Maddula’s death particularly jarring was how normal the events of his night played out: He attended several parties a few blocks off campus, traveled primarily in a group with his friends and seemed coherent, according to a student who saw him that night. He disappeared the night of Sept. 22, two days after the class of 2016 arrived in Evanston.

Now, following the second alcohol-related death of a student in four years, administrators and student leaders are looking beyond policy changes — and toward educational improvements and a new “party monitor initiative” — in their quest to make drinking at Northwestern safer.

Hospitalizations come with a cost

Associated Student Government formed a five-member working group on alcohol policy and culture in spring 2012 with the goal of comparing NU’s policy to those of peer institutions. Though full amnesty — the waiving of all sanctions for students transported to the hospital because of alcohol and students who make the call for help — was initially a goal of the ASG working group, group chair Alex Van Atta wrote in an email to The Daily that it was abandoned to focus on more realistic goals rather than risk opening a chasm with the administration.

But between students and administrators, everyone shares the goal of reducing dangerous drinking.

Lisa Currie, NU’s director of health promotion and wellness, said a “ballpark figure” of about 100 students are transported to the hospital each year. That number spiked in the first month of the 2011 academic year to 21 — up from 13 and nine in the same time period the previous two years.

Alcohol transport numbers may be dragged down by high ambulance costs, which can dissuade students in need from accepting transport. Superior Ambulance Services, which provides ground transport for Evanston Hospital, 2650 Ridge Ave., charges an $800 base fee for a transport with an additional $1,650 per mile. The hospital is about a mile from South Campus.

Patricia Telles-Irvin, vice president for student affairs, said the number of students transported to the hospital because of alcohol is unacceptable.

“I’m very concerned with the amount of drinking taking place,” she said. “There have been too many transports for the size of our university. We need to assess the most productive way to change that, and students need to be involved in the conversation.”

But there is room for debate about whether a rise in transports is a negative sign.

“The reality is if people need help they should be where they can get the help, and if that’s the hospital, so be it,” Currie said. “That may not be really popular with hospital (emergency room) staff, but if that’s where a person needs to be to get the help that they need, I’m fine with that.”

‘Students are going to drink’

Click to expand timeline.

NU has roots in alcohol prevention nearly as old as the school itself. It went dry with the city of Evanston 80 years before Prohibition, when the 1853 charter forbade the sale of alcohol within four miles of its premises, according to the University Archives. The city and the school remained, at least officially, alcohol-free until the late 1960s, when a group of students began advocating for liquor licenses, finally getting the issue to a successful vote in 1972. The campus enjoyed a brief period of alcoholic freedom until the state drinking age was raised to 21 in 1980.

Today, both on-campus and off-campus drinking is forbidden for students under 21. Those over 21 may drink in residential halls and colleges, or in their off-campus apartments, but only with other of-age students. Nevertheless, police officers, administrators and community assistants acknowledge these rules are broken on a daily basis. Given the circumstances, students and administrators have to tiptoe the line between policy enforcement and student safety.

“Students are going to drink,” said Van Atta, McCormick junior and ASG’s vice president for student life. “As much as the administration hates to admit that they’re going to drink even when they’re under 21, I think we need to be doing a better job of making sure they’re safe when they’re doing it and focusing on safety rather than policing.”

Daniel McAleer, deputy chief of University Police, said a weekend hardly ever goes by that UP doesn’t receive a noise complaint about a location on or around campus, and that those investigations often include drunk students.

“We do have to deal with intoxicated students and making sure they can be transported to the hospital for treatment on most weekends,” he said. “That’s something the whole community is trying to reduce. Hopefully by watching out for their fellow students and making sure they drink responsibly, they can help to get them to a safe place.”

McAleer said UP generally does not look specifically for parties where alcohol is being consumed, instead responding when other residents have concerns about noise.

One McCormick sophomore, who was in Chi Psi fraternity before it was disbanded last year, said when the group had on-campus parties, they rarely encountered UP.

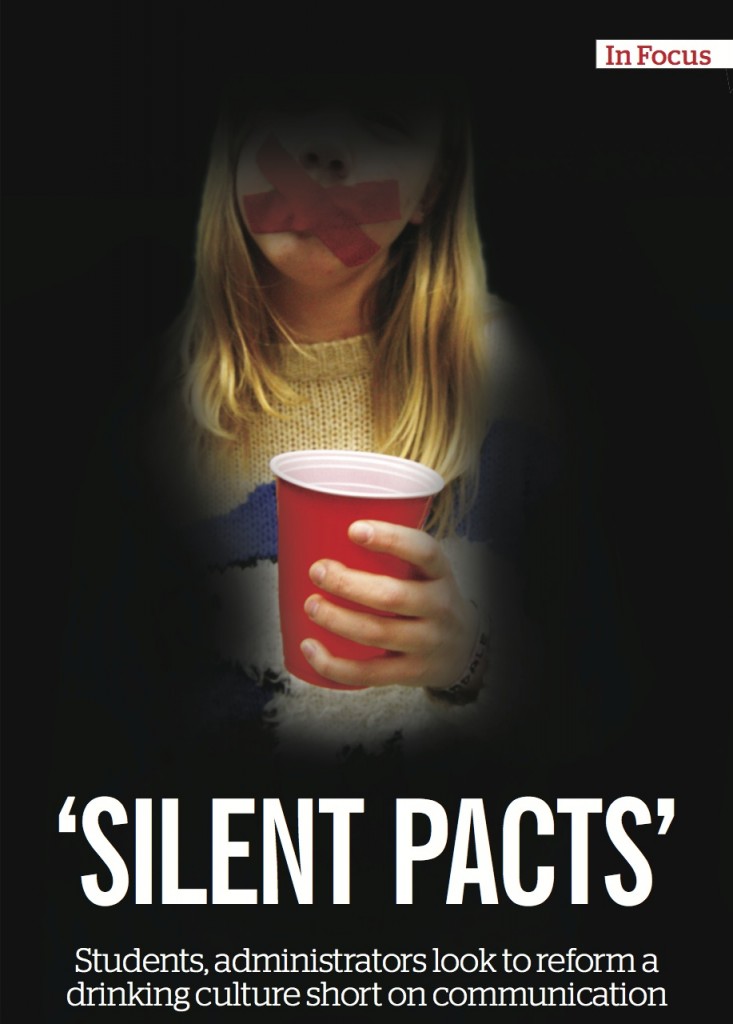

“The campus police hardly ever come through,” said the student, who asked to remain anonymous. “A lot of the drinking at this school is silent pacts: How much do you look the other way, and how much do you not?”

A tragedy brings reform

After the death of SESP freshman Matthew Sunshine in 2008, the University ramped up its safety efforts, instituting a number of alcohol education and prevention programs, including Red Watch Band training, reexamination of the Responsible Action Protocol and an alcohol resource web page. The new programs were part of a rider in the no-fault legal settlement between NU and the Sunshine family. Five years later, the University and Sunshine are still discussing pieces of the contract, as well as implementation of the rider, and dangerous drinking still occurs, said Jeffrey Sunshine, Matthew’s father.

Matthew Sunshine was found dead in his Foster House dorm room after consuming 17 shots of vodka in about an hour during a finals week drinking contest. After he passed out, the two upperclassmen he was drinking with carried him to his room, thinking he was asleep. When authorities found him in the morning, his blood alcohol content was .396, nearly five times the standard for intoxication.

“There is no reason that sober students for their amusement should be permitted to provide and encourage already intoxicated and incapacitated students to keep drinking until the intoxicated student needs to be rushed to the hospital or, as in the case of our son, is killed,” Jeffrey Sunshine said. “Northwestern needs to determine what kind of an institution it wants to create and what values it wants to instill in the students entrusted to it.”

The RAP was revised again in fall 2011, according to Jim Neumeister, assistant dean of students.

“The language of the RAP was modified beginning in the fall of 2011 to clarify that, if students follow the protocol – Call, Stay, Cooperate – they will not face formal disciplinary action for alcohol or drug offenses, and that the RAP also applies to groups and organizations,” Neumeister wrote Tuesday in an email to The Daily.

For his part, Jeffrey Sunshine believes in a reversal of the policy’s phrasing. Section 6 of the rider indicates the Sunshine family’s belief that instead of waiving or reducing punishment when students call for help, they should be punished unless they do so.

‘It’s a balancing act’

ASG is currently pushing risk management initiatives that may help students better look after one another. The group has pared seven initial recommendations down to three that it will push to the administration: expanded Red Watch Band training, improved education and the creation of a team of University-approved and funded “party monitors” who would stay sober at parties and provide assistance in dangerous drinking situations.

Van Atta said the idea is one that “a lot of people are on board with” and that has had success at other schools. In the study of eight peer institutions, the group found both Dartmouth College and Haverford College had successfully implemented similar programs. Dartmouth’s Green Team, which was founded in 2011, pays its members $40 per night to walk through a house party at 20-minute intervals. They are modeled off of Haverford’s “Quaker Bouncers,” a program that saw a 50 percent drop in alcohol-related hospitalizations after its first semester on campus.

There is also opportunity for collaboration with new dean of students Todd Adams. Adams recently left his administrative role at Duke University, which has a policy similar to NU’s in that it penalizes all violations of the state drinking age but offers leniency for those who make a call for help. At the beginning of this school year, Duke launched a team of party monitors to supervise on-campus drinking events. Student groups hosting on-campus social events are required to have one party monitor for every 25 guests and a licensed bartender to check partygoers’ identification.

Tom Mrva, a senior at Duke studying public policy, said party monitors at Duke have so far found an appropriate balance.

“They’re pretty effective at keeping people safe,” Mrva said. “They’re not trying to crack down on underage drinking, they’re just making sure things don’t get out of hand. If someone’s sick, they’ll look after them. If they have to call (Emergency Medical Services), they’ve been trained for that.”

Adams said finding that balance is crucial to the success of the program.

“Peer monitoring can be very effective,” Adams said. “It also involves a great deal of training and a great deal of trust. It involves a partnership among students and the administration and support by the entities that are hosting those events. It can be very effective when its done well. But if its not well-resourced or thought out, it can be less than effective.”

But implementing this kind of a team, especially if it is to be associated with the University, requires a level of trust and transparency between NU and ASG, Van Atta said. Party monitors will be there for safety reasons, not for “cracking down on every single party that happens,” while also “operating within the risk management desires of administration.”

“In some places, universities can be very hands-off,” he said. “But I think we do have a very conservative administration here as far as risk management and making sure we’re following all the rules … if this is something that the University wants to fund. It’s a balancing act that we have to figure out as we move forward.”

Once he begins his tenure in the dean’s office, Adams will chair the Community Alcohol Coalition, which will be reformed under his leadership.

Susan Cushman, alcohol and other drug prevention coordinator, said the coalition has existed in various forms for her three years at NU but began to dissolve with the recent reshuffling of administrators in the Division of Student Affairs. Cushman said she is looking forward to the coalition’s renewal.

“That’s really important to have both students and staff — and hopefully faculty — really engaged and actively addressing issues around alcohol and other drugs using a really comprehensive approach,” Cushman said.

In the meantime, the ASG group will also work toward mandating Red Watch Band training for student group leaders and increasing alcohol education.

‘I’m not sure if they completely understand’

Much of NU’s current educational programming comes from two Essential NU programs, AlcoholEdu and Wildcat Voices, Alcohol Choices, which are completed during the summer before freshman year and during Wildcat Welcome. Van Atta said the “information overload” of Wildcat Welcome means alcohol education can get lost in the shuffle.

“If that’s the only time (new students) hear what the alcohol policy is, then there are a lot of misconceptions about what it is at this school, in terms of individual amnesty, caller amnesty or organizational amnesty,” he said. “Students know that we have an alcohol policy, but I’m not sure if they completely understand what exactly it is or what their rights are when it comes to drinking alcohol.”

ASG’s data, compiled in a Fall Quarter 2012 survey, backs that up. Just 58 percent of students said “caller amnesty when you call for a friend” was included in the Responsible Action Protocol.

In fact, the policy says that “no formal University disciplinary actions or sanctions will be imposed for alcohol or drug infractions, but the incident will be documented, and educational, community, and health interventions — as well as contact with a student’s parents or family — may be required as a condition of deferring disciplinary actions or sanctions.”

Currie said certain myths need to be cleared up, particularly among students who would like full amnesty for anyone making a call and anyone being transported.

“There’s this belief that amnesty is sort of this ‘get out of jail free’ card, and it’s not,” she said.

Still, she emphasized that the biggest thing a student who follows the policy will get is a “big thank you” and said since she came to campus in 2009, she’s seen significant progress in education about the policy.

“I ran into students that first year who were like, ‘Oh my God, if I call for a friend, we’re both going to get suspended,’ or ‘Our chapter is going to get disbanded immediately,’ these really extreme sort of beliefs that I think had kind of developed through the grapevine through misinformation,” she said.

But the anonymous McCormick sophomore said the consequences can still be prohibitive.

“There’s a stigma around reporting because of the trouble you can get in,” the student said. “They discourage kids way too much for seeking help when they need it. I know a ton of friends that that’s happened to.”

Another aspect of education is programming, like AlcoholEdu, that focuses on the harmful effects of binge drinking. But one difficulty is that students, particularly those who were not heavy drinkers in high school, don’t absorb the information until it’s too late.

One male junior, who asked to remain anonymous, was returning from a fraternity party in 2011 when he stumbled in a Sheridan Road construction project and fell asleep. After being discovered by a group of students, he returned to his South Campus residential college and vomited in front of the community service officer, who called for him to be transported to the hospital. His story was not an anomaly.

“I wasn’t a very experienced drinker,” the student said. “I barely drank in high school, once or twice I think, and coming to college I started drinking a good amount. There was one night where I just got separated and started drinking kind of irresponsibly … I definitely blacked out at some point and did not know where I had taken those last few shots.”

The student called his hospital visit “a lesson learned the hard way.” He said though alcohol education programs like AlcoholEdu provide useful information, they fail to present students with the real-world impact of their actions.

“The problem is that when you take that, I feel like that’s more of an exam that you’re doing, something you’re doing to get it done,” he said. “You’re learning about a subject, and when you actually go out and drink, it’s totally different because nobody counts their drinks, nobody actually measures out an exact shot and says, ‘OK, here’s one shot, let me wait 15 minutes.’”

Patricia Hilkert, director of new student and family programs, plays a major role in shaping the Essential NUs. She said cases like this student’s are ones the administration is intimately familiar with.

“There are some college students who, no matter how much programming you do, their main goal is going to be to drink a lot,” Hilkert said. “The students here probably work hard and play hard. Our job is to make sure they know about all the resources and how to be safe if they do decide to experiment.”

The student, like all NU students who are transported to the hospital, then entered Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS), a two-session program through the Department of Health Promotion and Wellness. Though BASICS is what is known as an “early intervention” program, the department’s educational programming is meant to be preventive as much as it is protective. Cushman, who coordinates BASICS, said its efforts often center around “this idea of helping to avoid these problems from the get-go.”

‘The freshmen are going to get wasted a lot’

On the University web page “Real NU Party Habits,” the administration points out that 23 percent of NU students do not drink and 50 percent drink in low-risk quantities (fewer than seven drinks a week or 14 drinks a week for females and males, respectively). ASG’s recent student survey supports that claim, citing only 11 percent of students as consuming seven to nine drinks per week and 37 percent as consuming four to six per week.

Publicizing this information is also a focus of the ENU during Wildcat Welcome. Cushman said one of the goals for incoming freshmen is “letting them hear from other students who either drink in moderation or not at all so that they have Northwestern student examples to look to.”

But Carolyn Jones, a former community assistant, said kids are always going to feel pressured to drink and even one night of heavy drinking for a student who has never tried alcohol before can lead to a dangerous situation.

“Northwestern is a party school. Nerdwestern, Northwasted, Nerdwasted. Kids really like to drink,” Jones, a McCormick junior, said. “College is supposed to be this big party environment. Everyone’s seen ‘Animal House,’ it’s like nuts. College is drinking.”

The problem with this attitude, she said, is that new students will go out to Greek houses and drink with near-strangers because they are not permitted to drink in their dorms. She said the dry policy in dorms encourages “heavy drinking in small dark places with locked doors.” It forces students to go out to parties and not come back because they do not want to get in trouble, she said.

“The freshmen are going to get wasted a lot, and they’re going get wasted however they can,” she said. “And if you make them nervous and scared, then they’re gonna do stupid things, and they’re going to do it quietly and silently and then when they are in trouble, you’re not going to be able to find them.”

The anonymous McCormick sophomore said although off-campus drinking is often preferred to avoid the watchful eye of police and administrators, there can be safety issues with transportation.

“Off-campus drinking is very different,” the student said. “It’s better and worse. But you have to drink off campus because of the liability and rules here. And it’s definitely not as safe.”

The student told the story of finding a friend passed out in the snow who would have been in significant danger if he and his friends hadn’t helped him.

Sober alternatives

Jones also cited the lack of sober programming in dorms as a factor in the drinking culture, saying the dorm is “not a place that people feel like it’s cool to hang out on the weekends.”

In response, NU and ASG have provided funding for NU Nights, a new student group that creates late-night, alcohol-free programming on weekends. The group, which formed last year, is now expanding to partnerships with other student groups so sober programming is offered every weekend.

“There is a big drinking culture at NU, but there’s a lot of students who de-stress and relax in different ways — who enjoy just having fun,” said Rachel Galvin, a Weinberg junior and the incoming president of NU Nights. “I think NU Nights provides a space for that.”

Another issue that arises, particularly with cultural changes, is difficulty in measuring the impact of new initiatives. Cushman said the department uses a multi-pronged approach, implementing evidence-based solutions and constantly soliciting feedback.

“We don’t just do programs because they feel good,” she said. “We want to provide quality types of programs here.”

Currie said changing the culture can be even more difficult than changes to policy or additions to programming and can undermine even the best administrative efforts.

“If the social environment says, ‘Well, it’s OK to drink,’ or ‘It’s preferable that you don’t make that call to get somebody help,’ then that places enormous pressure on the individual to go with what the social environment says rather than what the policy says,” she said.

Telles-Irvin, who was hired in 2011 from the University of Florida after cracking down on binge drinking at the school, said in the end, the administration needs to partner with students to curb the destructive impacts of alcohol abuse.

“Students come here with expectations and ideas about their life, about how to make a contribution to society when they graduate,” she said. “I want to make sure those dreams happen. It’s really hard when people aren’t able to reach those dreams because of alcohol. We need to be partners with students to help them achieve those goals.”