Damien Echols, who was wrongfully convicted of murder and subsequently released from death row, spoke Tuesday at Northwestern about his experience and advocated for a more humanitarian justice system.

About 100 people gathered in Harris Hall for “Life After Death” with Echols and his wife Lorri Davis in an event sponsored by Northwestern Community Development Corps and the Peace Project. Echols said he is the only person who has ever been acquitted from death row in Arkansas.

In 1993, Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley Jr., was convicted in the murders of three 8-year-old boys in West Memphis, Tenn. Echols was sentenced to death, while Baldwin and Misskelley received multiple life sentences. The West Memphis Three, as they became known, garnered much attention over the years because their convictions lacked evidence. On Aug. 19, 2011, the men were released from prison after 18 years.

In 2007, forensic testing of the crime scene did not match the DNA of any of the three, according to a New York Times article. Following this revelation, the men’s lawyers began working on a plea deal, called an Alford plea, that allowed the men to maintain their innocence while acknowledging they “are pleading guilty because they consider it in their best interest.” Minutes after entering this plea, they walked as free men, according to the article. Echols said the men are continuing to pursue full exoneration.

At Tuesday’s event, Echols talked about life in prison. He began his speech with a retelling of when he was taken to a holding cell known as “the hole” after his initial arrest. Echols said this dark, dirty cell was separated from the rest of the jail, and for 18 days after he was brought there, officers would take turns beating him. Echols said he was saved from the potentially fatal situation by a church deacon who threatened to expose the officers if they did not stop.

“When you’re in prison, you never make any memories you want to remember,” he said.

Following his abuse in jail, Echols had an equally traumatic experience in the courtroom. Echols explained although he is depicted as calm in pictures from the trial, he felt far from it during the the proceedings.

“When the judge is reading in a monotonous, boring voice, I felt like I was being beaten repeatedly,” he said.

After he was convicted of the murder and sentenced to death row, Echols said he found solace in writing.

“(Writing) is the closest sort of thing to therapy you get in prison,” he said.

He said he soon began penning and receiving letters, eventually meeting his wife, Davis. Echols explained writing helped him forge new memories for himself that countered the horrible ones he was making on a daily basis in prison.

“When I was writing letters, I was doing it 50 percent for myself, and 50 percent for someone else,” Echols said.

Echols attributed his survival in prison to his relationship with Davis and the practice of meditation and energy work.

Following his speech, Echols engaged in a question-and-answer session with the audience where he discussed the media’s role in his trial and society’s treatment of prisoners.

Jude Cooper, assistant director for the Center for Student Involvement, attended Tuesday’s event and said it was “fantastic.”

“I thought the way he described it helped to bring back how horrible it was, and I think as Americans we become responsible,” she said.

NCDC and Peace Project sponsored the event to spread awareness of Echols’s experience while educating people about the justice system and pointing out its flaws.

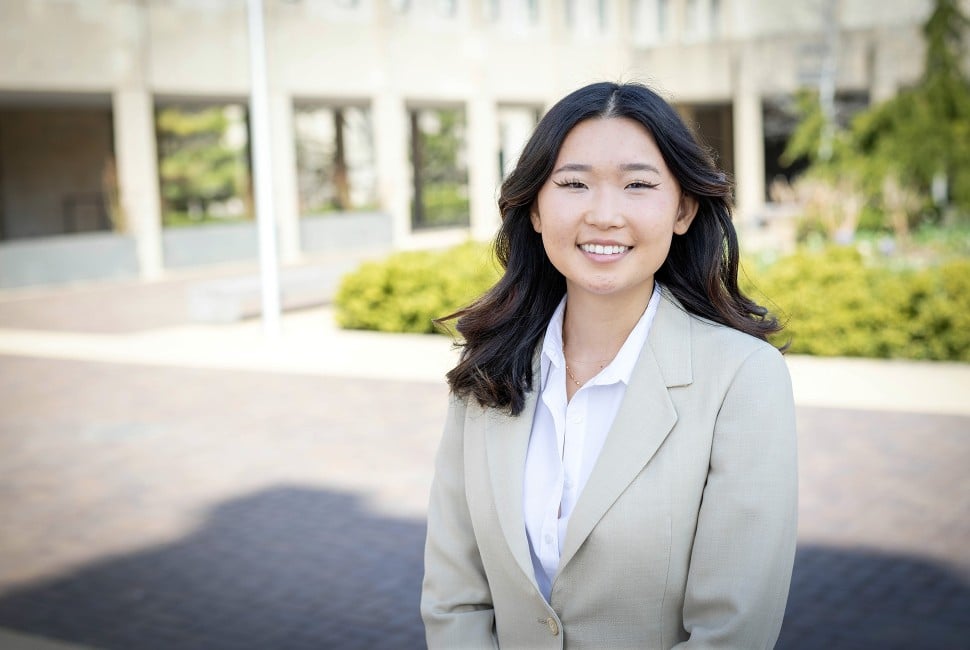

“The event is about citizens receiving a fair trial and correct treatment of justice,” NCDC co-chairs Amalia Namath and Stephanie Kim wrote in an email to The Daily. “We are advocating for everyone to have equal rights and no discrimination in the justice system.”