In January, a group of students held a meeting at the Black House to discuss the recent harassment of a Latina student. There, “The Collective,” an unofficial group of students working to promote greater cultural sensitivity on campus, was born.

The name has since dissolved, but its leaders remain at the fore of a new, more aggressive push for student awareness and administrative action.

Two weeks ago, Weinberg senior Kellyn Lewis, a former member of “The Collective,” snapped photos of students in offensive costumes depicting different cultures and ethnicities at an off-campus, Beer Olympics-themed Ski Team party. Photos with the students’ faces blurred out were posted online, along with an account of the event and an apology from the Ski Team. The party has since been branded by Lewis and others as “The Racist Olympics” and has sparked a series of forums, debates and student group-sponsored events. Those same students successfully pushed for the unprecedented release of an internal report about campus diversity by University administrators.

The Beer Olympics party has reignited a campus-wide conversation about diversity that has flared up for years at NU. The spirit of The Collective has been a driving force behind the latest push for cultural sensitivity on campus.

“It’s encouraging to see people kind of get angry for once,” said Dallas Wright, one of the students involved with The Collective. “To me, a forum or a panel discussion, a Facebook campaign, are very passive actions. We want people to take direct, aggressive actions, because that’s how you assert your will and how you make strong claims to the University.”

The group spent the week mobilizing other students and publicizing the cause across multiple platforms.

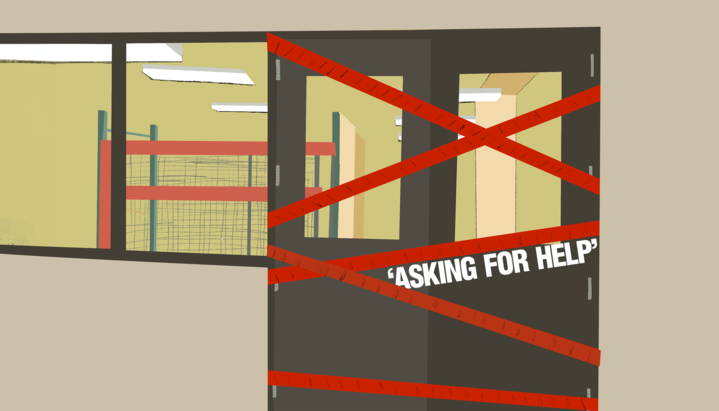

Students plastered the sidewalks with flyers. Almost 200 people flocked to an open Associated Student Government forum. Students signed a petition for the public release of an internal diversity report. They demanded the document by April 30, and even planned a blockade outside administrative offices. On April 26, University officials posted the report online. Instead of demonstrating at The Rebecca Crown Center the next day, students took to Deering Field to discuss issues of race and diversity.

The outcry reverberated through social media. A Tumblr site, The Post-Racial Northwestern, surfaced, briefly displaying blurred-out images of costumed Ski Team members and sharing videos of Lewis speaking at the Black House meeting and clips from campus publications.

“This could have been any group,” said Ski Team president Matt Dolph, a McCormick senior, in an April 25 interview. “There are so many events like this every week on campus that this could have been anyone else.”

And according to students, professors and administrators close to the movement, it isn’t about the Ski Team. It’s a rally against a culture of racism, an outgrowth of tensions that have been brewing for years.

“People come here to be educated, to learn from each other,” Wright said. “And the University has failed repeatedly and historically.”

For one goal, many names

The Ski Team’s party came just months after January’s Caucus Against Racial Prejudice, a student-led forum following the verbal harassment of a Latina student as she walked home late at night. Like the Beer Olympics, students learned of the incident by reading a letter posted on Facebook.

At a follow-up meeting at the Black House, five student organizers – including Lewis, Wright and outgoing Alianza president Hayley Stevens – introduced The Collective.

“We’re not here to fight racism. We’re here for diversity,” Lewis said Jan. 21. “We want to create a movement, a campaign for diversity.”

The Collective was informally divided into three tiers: main planners, frequent participants and those who supported its cause but didn’t engage in planning, said Communication sophomore Lucia Leon, an incoming Alianza president who said she worked in the second tier and attended many meetings.

But one quarter later, The Collective has fizzled out. Wright said the group never intended to cement itself as an official organization. Although students no longer meet under the name, he said The Collective’s mission lives on through the current efforts of its founders and has expanded.

Stevens said The Collective “doesn’t really exist anymore” because members became busy with midterms and finals. Still, she agreed that the group’s goals remain.

“Honestly, I never really felt like The Collective worked as an official name,” the Weinberg junior said. “And I think we’ve been operating really well as an unofficial, really random bunch of people.”

Another group, NU 4 Diversity Now, did emerge from the Ski Team incident. NU4DN now runs NU Collective Stories, a website featuring students from different backgrounds discussing diversity, and planned the event on Deering. However, the movement is not strictly an NU4DN initiative. Sofia Sami, co-president of the Muslim-cultural Students Association and a member of the ASG Diversity Committee, said the loosely structured, independent nature of students’ reactions to the Beer Olympics indicates the scope of the problem.

“It means you don’t need the title of an organization to care about it,” the Weinberg sophomore said. “The only title you need is to be a student at this University, and that alone should be enough to motivate you.”

Wright explained that leaders of the movement intended to steer clear of becoming a formal student group because they thought it would be limiting. Students, he said, may be “turned off” by name recognition.

Powerful ties

Despite the informality of the group’s structure, most of the students in The Collective had held high-ranking positions in various cultural campus groups for years, which gave the group access to administrators.

“They’re able to build relationships with administrators over their four years, and they also have a lot of prevalence on campus among the student population,” Wright said. “When they speak, students listen, and the administration listens, because they are the sort of major players on campus.”

Just four days after the Ski Team party, the University sent out an email to the NU community. Signed by Vice President for Student Affairs Patricia Telles-Irvin, Provost Dan Linzer and President Morton Schapiro, the letter commended the courage of the students who brought the incident to light.

At the Black House meeting two days earlier, Lewis said Dean of Students Burgwell Howard had called him to talk about the issue. Dolph, the Ski Team president, told The Daily that he also spoke with Howard.

“He expressed that he knows (Lewis and other students involved) well, that he has interacted with them before, but he showed no signs of bias,” Dolph said.

In an email to The Daily, Howard confirmed he knows Lewis and “his friends” but said he commonly forms connections with students and communicates with them when issues arise.

Later, Howard spoke about how the range of students supporting the movement reflects the message that issues of diversity affect everyone, not just certain cultural clubs. Furthermore, it allows them to reach students who aren’t minorities.

Howard attended a forum about self-segregation Wednesday called “Why do all the Asian kids sit together?” He said most students there were Asian, some were black or Latino, but only a handful were white.

“That’s not the demographic of the University, so how do you engage those other students to particip

ate in that conversation?” Howard said. “The challenge oftentimes from an administrator’s standpoint is, ‘OK, who are we speaking with and is this person or collaboration of people representative of the student body as a whole, or is this a specific initiative?”

A long-standing problem

NU has a history of racial unease that has prompted the formation of various diversity initiatives. The names have changed over time, but the claim of cultural insensitivity on campus has remained consistent.

Professor John Marquez teaches students in his African American and Latino Studies classes about the limitations of liberal multiculturalism, or the idea that Americans view diversity as a chance to “add on a respect paid to the history” of various minorities rather than reevaluate the white, hegemonic power structure.

The racial climate at NU, he said, is similar to problems plaguing many peer institutions since the mid-20th century: Administrations make efforts to quantitatively enhance diversity through courses, programs and enrollment instead of focusing on making minority students feel comfortable on campus.

“I think what students are feeling antsy, if not angry, about, is a wariness that they are merely being added on for public relations purposes, that they’re being used to kind of narrate an image of diversity that doesn’t quite problematize the status quo, the core foundations of the University,” Marquez said. “I think that’s a reflection of the post-Civil Rights Era in general – let’s just add a month to celebrate ‘blank.'”

When Marquez helped to moderate January’s Caucus Against Racial Prejudice, it was a familiar position for him. In 2009, Marquez also participated in campus-wide conversations when students wore blackface for Halloween.

The spring before, a black student said he was racially profiled by officials while studying inside the Donald P. Jacobs Center.

That student, Joshua Williams, said he was stopped four times by NU staff and asked to show his WildCARD, according to a 2010 Daily article. His claims led to a forum attended by about 600 people, which in turn resulted in the creation of “Inclusive NU” project.

Perhaps the most famous confrontation between the University and black students was the 1968 bursar takeover, when 97 students protested administrators’ refusal to respond to a list of demands by chaining themselves to the Bursar’s Office. Their stipulations echo what students petitioned for this year: adding diversity courses to the curriculum and recruiting more diverse applicants. A few years after the bursar takeover, the African American Studies department was created.

Subsequent movements have been less radical, favoring discussions over demonstrations.

But the long-term effects of these short-term movements is less clear.

In 2007, then-freshman Halle Bauer (SESP ’10) was troubled by the degree of self-segregation she witnessed among racial groups on campus. Around the same time, a Daily columnist wrote a contentious piece arguing that minority groups cluster together and inhibit diversity. Fallout from the column ignited a 125-student “March for Unity.” Inspired by the events, Bauer formed the Race Alliance Northwestern, a discussion group for students of all backgrounds to talk about their experiences.

“There were a lot of places on campus for affinity groups to get together and discuss – the Black House, various classes – but I didn’t feel like there was a space for everyone to go and feel comfortable connecting,” said Bauer, now an advisor for the Student Group on Race Relations at Shaker Heights High School in Ohio.

During her time at NU, Bauer said RAN organized weekly meetings that usually attracted about 30 people. RAN also hosted two leadership summits for members of various cultural groups to come together. Though she considers those events successful, she said there was never any “follow-up” beyond them.

Despite her best efforts to recruit younger leaders, Bauer said the once-visible campus organization disintegrated after her class graduated. Cultural groups were more concerned with bringing big speakers to campus than talking to each other regularly, Bauer said, and RAN lost its purpose.

“In many ways it’s almost controversial for me to say this, but the student group structure at NU is sort of isolating,” she said.

Professor Nitasha Sharma said students taking action after the Ski Team party seek to unite the different student groups that already exist just as RAN, which she helped advise, tried to do. The difference, she said, is that where RAN promoted talk of race, students now want to discuss diversity.

“Efforts to make changes clearly have been unsuccessful because this culture continues,” Sharma said. “The role of this University is to educate students about why these things are not OK…and if people are graduating Northwestern without understanding that, then we’re not doing our job.”

‘This isn’t a black-and-white matter’

To avoid a fate like RAN’s, Wright said the movement’s de facto leaders are working to involve young members. He said juniors and sophomores are already enthusiastic and assuming important roles. Seniors, Wright said, may be more vocal now because of their unique experiences at NU. They witnessed the blackface incident, have forged relationships with cultural groups and are members of a class with record low black enrollment.

“We are trying to help the administration and do what the administration claims to be working toward, but for whatever reason, we seem to want it quicker,” Wright said. “In some ways, you’re going to graduate soon, so you’re a little bolder in what you’ll say or do, maybe because you might not have to deal with a bias or any consequence since you’re in your later years at school.”

Moving forward, African Students Association president Michelle Byamugisha, a Communication sophomore, said she hopes to change campus culture so that ignorance is no longer acceptable. To achieve this, she said the collaborations and conversations following the Ski Team party must persist.

“The conversation can’t be confined to the African student coalition,” she said. “This isn’t a black-and-white matter. There are so many different perspectives that need to be considered.”

At the ASG open forum, Telles-Irvin said the administration is working to meet students’ requests. The University has already created and filled a diversity officer position and released the diversity report. The Weinberg dean, she said, is speaking with students about implementing a cultural competency academic requirement. In an interview with The Daily, Howard said he is developing a resource students can use to report racially-charged aggression.

But top-down changes take time. Howard encouraged students to continue the dialogue about race and learn from each other’s experiences.

“It’s not me having a party or talking to a young woman as she gets off the shuttle. It’s not the provost,” Howard said. “It’s the students.”

Patrick Svitek contributed reporting.