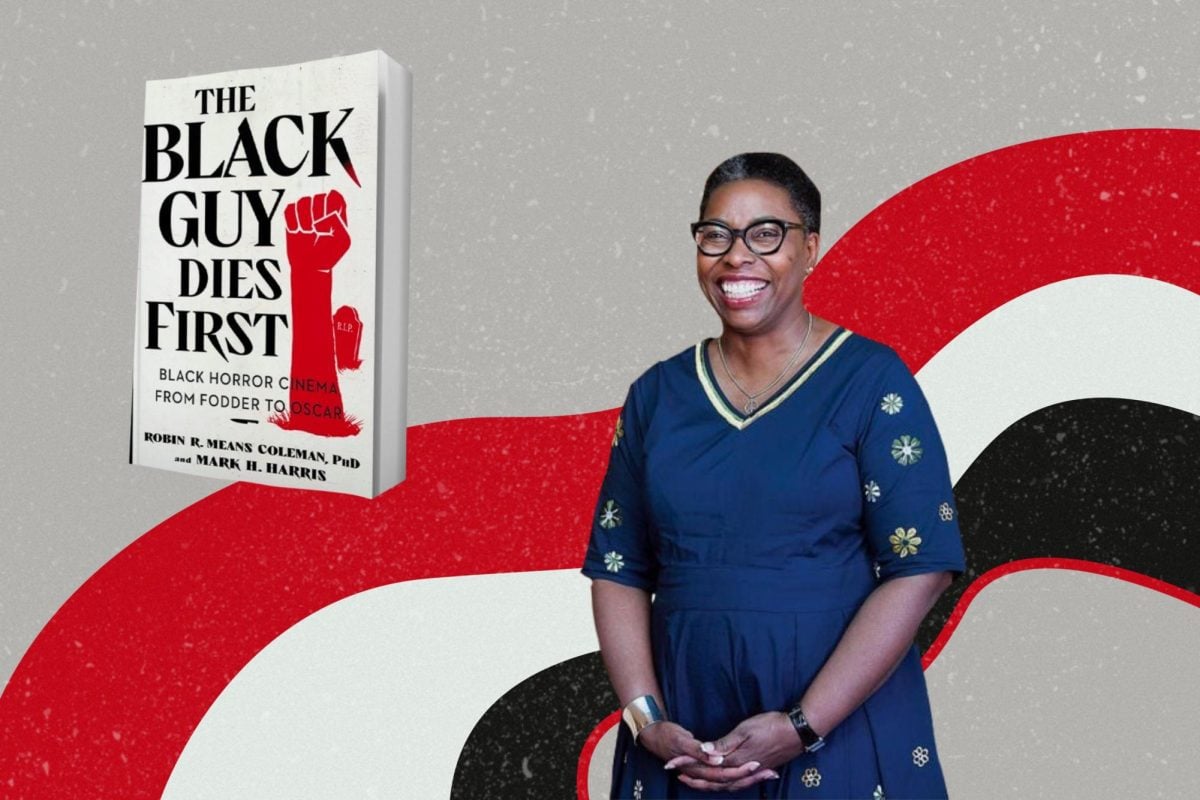

In 2023, Communication Prof. Robin R. Means Coleman, vice president and associate provost for institutional diversity and inclusion, published the second edition of her book “Horror Noire: A History of Black American Horror from the 1890s to Present.” She also published “The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema from Fodder to Oscar,” which she co-wrote with entertainment journalist Mark H. Harris. Both titles explore the representation — and lack thereof — of Black characters in American horror films.

The Daily sat down with Coleman about her research on Black horror films and her work promoting diversity and inclusion at NU.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Daily: The title “The Black Guy Dies First” references a horror trope. What message are you trying to convey through that title?

Coleman: (That trope) happens particularly in horror films where Black people appear, versus Black horror films.

In Black horror movies, the Black guy typically doesn’t die first. And we’ve got more than a century of films that talk about the ways in which Black people were represented as whole and full characters, who advance a narrative, who are central to and critical to the story. It reels you in, but then we hit you with some pedagogical stuff that’s also really funny.

The Daily: The book takes on a humorous tone. What kind of voice are you trying to develop throughout it?

Coleman: “Horror Noire” has the more serious scholarly, pedagogical tone that people use in the classroom. I didn’t want to lose that teaching moment in “The Black Guy Dies First,” so the approach is more accessible, and it represents (my and Harris’) style and personality.

The two books have a similar goal, which is to help people understand how Black folks are represented in media, specifically the horror genre, and both books show how Black horror takes up a theme of activism and social justice.

The Daily: To what extent have Black horror films advanced messages about activism and social justice?

Coleman: Many tend to be message movies that speak directly to the Black experience, and that experience is often enveloped in social justice.

It doesn’t mean that Black horror movies are always message films, but that is what often comes up if you’re focusing on Blackness ― which is Black life, experience and history.

The Daily: How does this focus on Blackness intersect with explorations of gender and sexuality?

Coleman: There are Black women (in some horror films) who are fighting on behalf of the larger Black public. What we don’t see enough of is sexual diversity in horror films. We need to be careful how we represent deaths when we’re in the middle of such a homophobic and transphobic climate. There needs to be a balance of that heroism and the violence.

The Daily: How does your research on Black horror connect to your work promoting diversity and inclusion?

Coleman: Horror reminds us that if we continue to fail in the arenas of social justice, not only will we see the need for activism, but even if that continues to fail, we may see a shift from civil activism to even moments of uncivil activism, so there’s a lot of runway before we get to that moment where we have an opportunity to get things right for our community.

Email: edwardcruz2027@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @edwardsimoncruz

Related Stories:

— Search committee formed to name leadership for Civil Rights and Title IX Compliance office

— Northwestern receives award for work on diversity and inclusion

— Robin Means Coleman discusses student activism, vision for equity