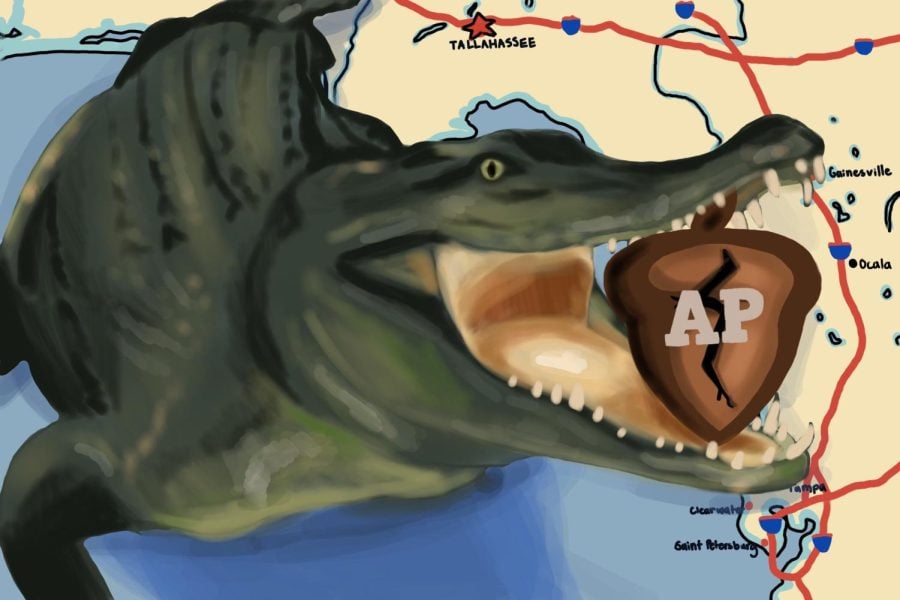

Professors and Florida students discuss College Board skepticism and AP class bans in the state

Floridian Northwestern students reflected on their experiences with the College Board in the wake of the state’s actions against Advanced Placement classes.

April 10, 2023

When McCormick and Bienen freshman James La Fayette Jr. committed to Northwestern, he had four college credits under his belt. By the end of his senior year at his Florida public high school, he had taken seven Advanced Placement courses.

But future Florida students may be coming to college having taken none. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has discussed ridding the state of AP courses and the College Board, which creates the classes, in a February press conference. In January, he banned AP African American Studies.

“They are just kind of there, and they provide a service, and so you can either utilize those services or not,” DeSantis said during a February news conference.

La Fayette Jr. said he doesn’t like colleges’ reliance on the College Board. Still, he said, banning AP courses hurts Florida students because it removes access to university-level classes that are accepted for college credit nationwide.

He said AP Calculus AB and AP Physics provided him a good foundation in STEM at the University, preparing him for classes like engineering and calculus.

“I feel that AP classes really set me up for success in my later classes,” La Fayette Jr. said.

Communication freshman Julia Polster took AP Physics to improve her GPA.

At her Florida private high school, Polster said AP classes were largely about prestige, but taking many AP classes wasn’t worth it to her. She said college counselors encouraged students to take as many APs as possible for college applications.

“People just loaded their schedules,” Polster said. “By senior year, I was sort of like, ‘I don’t care because there’s just more to high school.’”

Polster said she would be fine with Florida moving away from the College Board because she “absolutely hated” the SAT. Removing standardized testing would have alleviated some of the pressures she faced during high school, she added.

She said although Florida students may have a harder time applying to colleges, there are other attributes of their applications that colleges value more.

Denise Pope, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education who has researched the impact of AP programs on success in higher education, said colleges evaluate applicants in the context of their schools’ resources, which may allow Florida students to still compete without AP classes.

Pope said College Board tests create equity issues because wealthier schools offer more APs and better preparation. Because DeSantis can only influence public institutions, she said, banning APs may only further the inequities in education.

“A lot of Florida kids, particularly those who are wealthy, are going to pay on their own and take the test,” Pope said.

There might be a migration of students to private schools if the change were to occur, Pope said.

SESP Prof. Timothy Dohrer said the “billion-dollar industry” behind education is the reason why Florida is getting so much attention.

“Florida is one of the number-one purchasers of the College Board’s various curriculums,” Dohrer said.

Pope said Florida’s large population would cut into College Board’s profits if there was a ban, but a state like Rhode Island banning the College Board would not spark the same attention.

Dohrer said DeSantis’ political motives are mostly against some of the College Board’s AP course contents, rather than its operation. He said he thinks it’s a tough decision for DeSantis to make because many Floridians may not agree with the choice.

The “push and pull” of politics in education has been going on for more than a century, and Dohrer added these situations can be beneficial in helping students learn about debate and democracy.

He said students should be a bigger part of conversations around their education.

“I think we should be asking students about whether or not they think they should be learning certain things,” Dohrer said. “It’s worth our time to listen to (our kids) and give them some voice because I think we can learn a lot from them.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @LuisCasta220

Related Stories:

— ETHS teacher who shaped AP African American Studies discusses threats to curriculum

— School Board races take center stage ahead of election day as early votes are cast

— District 202 Board of Education discusses equity of AP enrollment, access