Daniel Nissani hates asking for money.

For his first three years at Northwestern, the SESP senior was mostly self-sufficient thanks to his Pell grant, a federal scholarship issued to students with financial need. But because his mom received a pay raise last year and a chunk of his financial aid was rescinded, he has had to lean on her more heavily than ever.

Even with two jobs and a monitored budget, Nissani expects the rest of Fall Quarter to be rough.

Nissani is one of hundreds of students who qualify for a Federal Pell Grant by the Free Application for Federal Student Aid’s standards — the same group of students the University defines as low income.

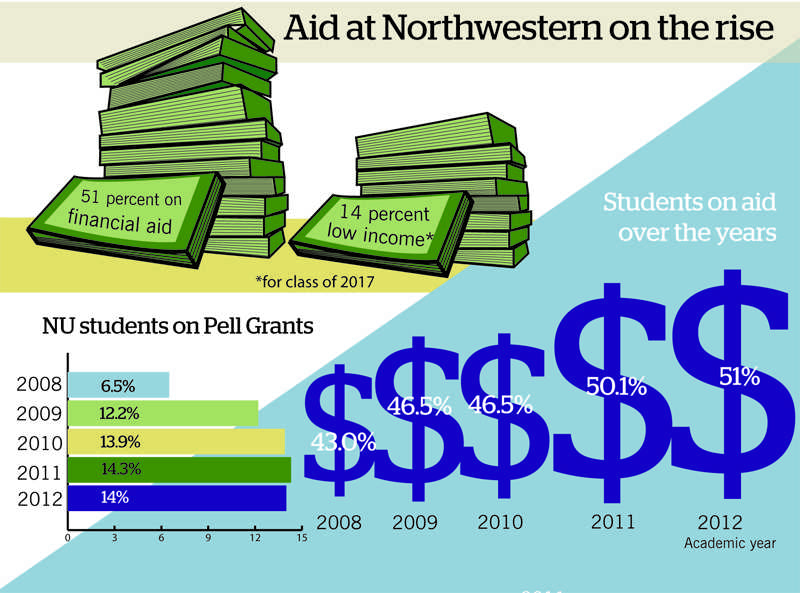

Low-income students comprise 14 percent of the class of 2017, and last year comprised 13 percent of the entire student body, which Nissani said makes them one of the largest but least visible minority groups on campus. As a co-president of Northwestern Quest Scholars, NU’s only low-income advocacy organization, Nissani has been on a two-year campaign to give these students the support and resources they need to excel here — resources already available to students in higher income brackets

Coming from a lower-class background and grappling with financial stress can make students feel lost and socially alienated, and they don’t always know where to go for help, Nissani said.

“It’s all just to make them feel that they belong on campus. That they really can do this,” he said. “Acclimating is really hard for some of us. …To hear someone be like, ‘My dad just went on his private plane to another country for fun,’ that’s really biting.”

As the University draws more low-income students with every incoming class, Nissani’s experience resonates with a growing number of students. New admissions recruitment strategies, funded research from Student Affairs and input from student groups are all part of NU’s concerted effort to change its reputation as a “rich kid school” and include socioeconomic status in its definition of diversity.

‘A vicious cycle’

For Communication senior Daniel Flores, the hardest part about coming to NU as a first-generation college student was the culture shock of an elite environment. After attending an all-Mexican high school in San Antonio, one of the most economically segregated areas in the country, Flores found that being around people from wealthier backgrounds required adjustment.

“(Other kids) are not coming from public schools like mine,” Flores said, who is the other co-president of Quest. “There’s nothing wrong with that. But advisors, staff, other students, they treat you like you’re from there. So when they found out I was struggling, just learning about college because my parents didn’t go, the staff had no training and no idea what I was dealing with.”

A 2012 Kellogg Study found that first-generation students from community-oriented backgrounds have a harder time adjusting to college because their parents were unable to adequately prepare them. The study refers to a “culture mismatch” between first-generation students and those whose parents attended college. A closely related concept is “cultural capital,” a class-specific vocabulary and set of learned behaviors that low-income students may not be equipped with.

“(Low-income students) can feel like they have fewer resources to draw on than a lot of their classmates,” sociology Prof. Karrie Snyder said. “If you didn’t grow up in a middle or elite household and you didn’t go to Europe or a museum, those types of things can make students feel like they’re not part of an institution where there’s a wide diversity in socioeconomic statuses.”

Yjaden Wood, a dual-degree sophomore from a low-income neighborhood in Philadelphia, said he had to adapt financially to Evanston, where the cost of living is higher than the national average. According to a national Sperling survey, which ranks cities based on an index where “100” is the average cost of living, Evanston comes in at 122 for living expenses and 108 for food expenses. In comparison, the cost of living in Chicago is 105.

“(Evanston) is definitely a change from back home,” Wood said. “Back home we have the dime and nickel stores, which don’t really exist here. You go to CVS for everything, and it’s usually more expensive than it would be normally. I don’t shop at Whole Foods when I need anything because Whole Foods is expensive. I make the walk to Jewel-Osco.”

Wei-Jen Huang, assistant director for community relations at Counseling and Psychological Services, said low-income students have talked to him about feelings of isolation and exclusion. The stress of coursework and budgeting puts a lot of weight on students’ shoulders and makes it more difficult for them to participate in social life, he said.

“They don’t want to acknowledge they have less,” Huang said. “They don’t want people to pity them. They don’t want to create discomfort. So they find excuses not to go to those expensive places.”

Wood works three jobs outside the University in addition to a full course load and pays his own personal expenses, while also sending money home to his two siblings and saving 10 percent of all income in a “rainy day fund.” He lacks a working cell phone because he did not have the money to pay his last phone bill, but since he never had one growing up, he said it’s not a priority.

Wood does all of his budgeting in Microsoft Excel — a habit he picked up early in life — and tries to stick to recreational activities that are free, like visiting the Art Institute of Chicago, which now waives admission for NU students as part of a new partnership with the University.

“It becomes a vicious cycle if you let it,” he said. “You’re upset at the amount of schoolwork you have ‘cause you can’t work enough, and you’re upset at the amount of work you have because you can’t do your schoolwork enough, and you get angry at yourself and at your financial situation and it doesn’t really help you.”

A new kind of diversity

Last fall, Flores approached the Office of Student Affairs with the idea of organizing focus groups to learn more about low-income students. Conducted in the spring, the groups resulted in the recently compiled report “Undergraduate Students from Low-Income Family Backgrounds and the Northwestern Experience.”

The series, which involved about 50 low-income students in groups of eight to 10, found that the participants deal with added stressors that other students do not. Although the classroom experience is basically the same for all students, the social experience is very different, said Mary Desler, senior assessment analyst for Student Affairs.

“I was really impressed with the resiliency of these students,” Desler said. “They face hurdles that no one else does here, and they stick with it. And they’re really independent — most of them have been independent their whole lives.”

McCormick senior Chloe Frizelle, born and raised in Hawaii, became a legal independent at age 18 and has no family income to rely on. She has been saving money since she was young and has been able to figure out all of her NU expenses on her own, including some tuition. On campus, she is involved with Hawaii Club, women’s rugby, Cru. and Engineers for a Sustainable World.

Frizelle said she is generally happy and well-supported at NU but still feels different from most of the student body.

“Northwestern prides itself on this diversity that we have,” she said. “Maybe ethnic and cultural diversity, I’ll give you. But socioeconomic diversity? No. We do not have socioeconomic diversity. People don’t really come here unless they have a lot of money. …You walk around and everyone’s wearing North Face and Hunter Boots and Uggs.”

Lesley-Ann Brown, director of the new office of Campus Inclusion and Community, said the University is still learning how to better serve NU’s low-income population through an initiative called Sustained Dialogue, a student-led, 90-minute conversation about diversity held weekly on campus. Piloted last spring with 55 students, this fall 100 students are enrolled with nine groups meeting each week. It is a signature program of the Department of Campus Inclusion and Community that will continue to be offered in the future, Brown said.

One goal of Sustained Dialogue is to highlight less-acknowledged minorities, including low-income students. Economic status is a particularly difficult issue to talk about because both low-income and high-income students can be embarrassed about or ashamed of their backgrounds, Brown said.

“When people think about diversity at Northwestern they’re not thinking economic diversity, but I think that that’s beginning to change,” Brown said. “Once people start feeling guilty or ashamed, they don’t take in anything or they don’t give anything to the dialogue. Guilt and shame is not my goal.”

Creating a safe space

A key way to make low-income students more comfortable involves creating a forum where they can find and consult one another, Nissani said. Quest, founded two years ago, stemmed from the national nonprofit QuestBridge, which currently provides scholarships for 300 NU students.

NU is one of the biggest partners of QuestBridge, which pairs underserved students with top universities. With 95 Quest scholars, the class of 2017 has the highest number since the collaboration began in 2008.

After a lot of paperwork, the group finally opened its office in Norris University Center this fall. About 60 students attend Quest’s monthly meetings, but Nissani said he hopes to reach as many low-income students as possible, whether they are part of the QuestBridge program or not.

“The safe space is necessary for the same reason there needs to be a space to talk about race issues, LGBTQA issues, disability issues,” he said. “It’s because it’s an identity that isn’t necessarily accepted by everyone, whether it’s subconscious or conscious.”

Beyond providing a safe space, Quest also works with the University to assess barriers that exclude low-income students, such as expensive tickets to formal dances, Greek dues and Dance Marathon fees. Before Wildcat Welcome, Quest trained peer advisers about low-income sensitivity, suggesting they give students a heads up about how expensive a planned group dinner might be or discussing alternative options such as a potluck instead.

Last week, Associated Student Government unanimously voted to allocate $4,000 of the Senate Project Pool to subsidize DM registration fees for students in financial need. The money will be distributed by Center of Student Involvement staff based on level of need. David Harris, co-chair of public relations for DM and co-author of the allocation bill, said there have already been more than 100 requests for financial help.

Quest will have a DM team for the first time this year, and Harris said they are the kind of students he hopes will benefit from the ASG donation.

“It’s an opportunity for us to bring a broader audience to such an important event in our community,” Harris said. “It’s been really enlightening sharing our office with the Quest scholars. They for the first time have a Dance Marathon team and we’re excited to continue working with them.”

In addition to extracurricular and social events, Quest also provides professional resources. On Oct. 30, Quest will host a career event to discuss paid internships, research grants and other affordable work opportunities in the summer.

Unlike many NU students, who pursue unpaid internships to gain valuable career experience and bolster their resumes, Flores usually has to work instead. During the academic year he supports himself and his sister in Peru through two work study jobs — one at Hispanic/Latino Student Affairs and one as a tour guide. Long periods of time without income are not an option for most low-income students, he said.

Until this year, Medill students were not permitted to work during their quarter-long Journalism Residencies, a policy that has recently changed due to students’ financial concerns. Flores noted the difficulty of completing academically relevant work while saving money at the same time.

“I’ve let down some really amazing internships,” he said. “I did Chicago Field Studies and that was difficult, even though they gave me some money. I wasn’t allowed to work, so I was losing a large amount of income. I needed more money to pay for the train.”

A ‘responsibility to educate’

Recruitment efforts for low-income students increase every year and start before students even enroll, said Christopher Watson, dean of undergraduate admissions. Last year, 13 percent of the student body qualified as low-income, up from 8 percent in 2004.

In addition to QuestBridge, NU increases its visibility in low-income areas through other partnerships with community organizations. In the past two years, NU has teamed up with the Chicago Scholars, a nonprofit organization that guides Chicago students to college success, and the Los Angeles site of The Posse Foundation, Inc., a nonprofit that provides hundreds of Los Angeles public school students with scholarships each year.

NU enrolled 72 students of Chicago Public Schools in 2012, up from 28 in 2008, according to associate provost Michael Mills. For the class of 2017, 10 Los Angeles public school students came to NU with Posse scholarships, Watson said.

“Northwestern has a responsibility to educate all different kinds of students,” Watson said. “And all different kinds of students should be the beneficiary of an education here, and there shouldn’t be financial barriers to that.”

University officials emphasize that NU accommodates students of all socioeconomic statuses. Last fall, NU spent $118 million dollars on student aid, up from $94 million two years ago. The increase in financial aid has resulted in more students receiving help — 51 percent in 2012 as compared to 44.9 percent in 2006. This includes University aid, federal and state aid and outside grants and scholarships. Information about financial aid is distributed during tours and at Wildcat Days, for which prospective low-income students can request free or subsidized plane tickets in order to attend.

“There’s still the impression that it’s a wealthy, white student school — and especially because we’re on the north shore of Chicago,” Watson said. “The more we can present opportunities for kids to either see campus or meet Northwestern students that have a similar background, the better our recruiting results will be, and that just takes time.”

A need for support

In comparison to other universities, NU is generous when it comes to giving money to students in need, but it could use improvement when it comes to follow-up and support, Nissani said.

For example, when Nissani found his Pell grant was changing due to his mom’s new job, he was shocked and unsure about where to go for help. With a smaller refund for living expenses and a health insurance plan to pay for, Nissani and his mom have had to be extra careful this quarter. His mother, who lives and works in Queens, N.Y., has only visited campus once due to financial constraints and will probably not do so again until he graduates.

“If you’re low-income and your mom finally saved some money … does the University really think it’s appropriate to start zapping money from them?” Nissani said. “There are Quest scholars that are really distraught about this, who are like, ‘My mom got a new job, but I don’t know how we’re going to pay for school anymore.’ That’s our reality.”

When students are having trouble with their aid packages or anything else having to do with finances, it is difficult to get in touch with the right people, Flores said.

When Wood could not afford to fly home for Spring Break his freshman year, he needed to find a place to stay while Willard Residential College shut down for the week — a problem that proved more difficult than he expected. After being transferred back and forth between the housing and financial aid offices multiple times, he eventually found an apartment to sleep at through Quest. He said the administration is generally responsive to students’ financial problems, but does not always have programs in place to deal with them.

“In most cases, we’re all smart. We can figure it out,” he said. “It would be nice to have someone with more experience to direct you in the beginning when you have other things going on. It’s very hard to find the time, because you have to find the time to figure out a lot of your situation. Like where do I go, what should I do, how do I do this?”

This confusion, especially among new students, is part of why Flores and Nissani put so much effort into keeping the Quest community alive.

“NU doesn’t do a great job advertising how you go about things if you don’t have money,” Flores said. “You have to go through so many hoops to figure out the answer to a question; we want to make sure students have the right resources. There is a steep learning curve when it comes to being low-income at NU, and we’re trying to level that playing field.”

Email: samanthacaiola2014@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @sammycaiola