When housing assignments were released for the class of 2016, Communication freshman Alena Pranckevicius was a little confused.

Pranckevicius requested the options “north” and “big” on the housing preference questionnaire sent to new students but was assigned Rogers House, a South Campus dorm that houses about 50 residents. This academic year, incoming freshmen answered several general questions on a housing survey instead of ranking their top five dorm preferences as in past years.

“I was really unhappy,” Pranckevicius said. “I talked to someone who had already graduated about Rogers House, and that person said it was small, south and not very social. I went into it with an open mind, but I was realizing it was not what I wanted.”

Pranckevicius decided to fill out a request form to transfer residences, and a spot opened up in Elder Residential Community — an arrangement she now likes much better.

“It’s a lot more convenient to live in Elder — there are a lot more people,” she said. “I can expand my friendships.”

Pranckevicius’ story is not uncommon among incoming students initially disappointed with their housing assignments. Despite a revision of the housing application process this academic year to provide more choice, living experiences across campus still vary widely.

To remedy the disparity, the University and students have collaborated this year, collecting data and surveying Northwestern’s current housing options to identify areas for improvement.

The result is a comprehensive housing plan that would drastically alter NU housing over the next two decades, eventually adding 1,000 beds across campus. The ambitious proposal is expected to be completed this summer.

“We’re going to continue really improving existing housing stock for undergrads,” University President Morton Schapiro said in an interview with The Daily in April. “And then we’re going to add some.”

Shaping the college experience

Students point to several ways campus residences can be improved, ranging from the addition of overhead lighting to the creation of a more tight-knit living experience.

Associated Student Government president Ani Ajith admitted he and Alex Van Atta, ASG executive vice president, could have had a better first-year living experience.

“We both lived in residential halls that could have had facility improvement,” said Ajith, a Weinberg junior. “The residential living experience really shapes the rest of your experience in a powerful way.”

Paul Riel, executive director of Residential Services, said residential life presents many opportunities for students — community, tradition and ownership — in addition to proximity to classes and dining halls.

“On-campus living shapes how you live,” Riel said. “You create friendships and a sense of tradition, where you live and who you met along the way. When you come back as an alum you say, ‘I lived in that building.’ They are life-changing.”

A variety of living options

There are 31 residences on campus, amounting to about 4,200 beds, according to the Office of Undergraduate Admission. About two-thirds of the undergraduate population lives in University housing, and incoming freshmen are guaranteed a place in a dorm if they request it.

NU has 11 residential colleges designed to integrate students with a learning community outside the classroom. Elder and Allison are residential communities, which give students the opportunity to interact with a faculty live-in.

Five special-interest housing options, such as Substance-Free Community and Interfaith Living and Learning Community, are also part of University housing. A gender-open housing arrangement is currently located within Foster-Walker Complex.

Students involved with Greek life can also choose to live in on-campus fraternity and sorority houses.

Although many housing options are available to students, certain residences are more coveted than others, which can impact the undergraduate living experience. Newly renovated Allison, sometimes called “Hotel Allison,” has become a popular choice, while many students dread being placed in dorms that do not have air conditioning, such as South Mid-Quads Hall.

Weinberg sophomore Madeline Martel originally wanted to live in Elder but was assigned to North Mid-Quads Hall. She was initially upset but eventually made close friends.

“My floor really bonded because we were all freshmen,” Martel said. “It was like the Elder experience on a small scale.”

Creating a master plan

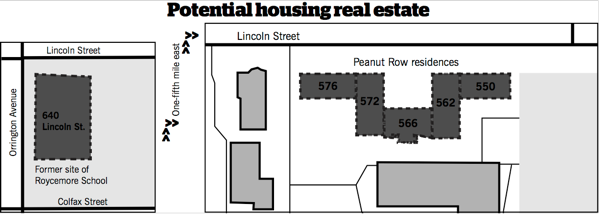

Infographic by Kelsey Ott/Daily Senior Staffer

In the fall, the University hired the program management firm Brailsford & Dunlavey to make recommendations for housing over the next 10 to 20 years. The plan’s completion is slated for this summer.

The working plan includes research about residential life from peer institutions, as well as data from the plan’s student housing survey that was reviewed by ASG, the Residence Hall Association and the Residential College Board. The next steps are to consider costs and compile information from Facilities Management.

“It’s a look at where could housing go and what buildings could be,” Riel said. “We have to be pretty specific and pretty strategic.”

Student feedback played a major role in the plan’s development, with several focus groups sharing their input.

The plan’s survey found many upperclassmen prefer single bedrooms, a shared bathroom and cooking facilities in close proximity.

“The older students want more privacy and autonomy,” Riel said.

Another section focuses on updating facilities to produce immediate effects, Riel said. The University will first target easy fixes such as adding blinds in Kemper Hall, improving NU’s mail system and placing furniture and technology in lounges.

Riel is working with a printer company to add free 24-hour printing to the residence halls. He also wants to expand the retail hours of Fran’s Cafe and Lisa’s Cafe, as well as add 24-hour front desks to Allison, Foster-Walker and Kemper.

Facility and financial assessments are almost finished, indicating the process is near completion, said Julie Payne-Kirchmeier, assistant vice president for student auxiliary services. Because the plan “takes a look at the whole program holistically,” it will allow NU officials to prioritize what areas most need attention, she said.

“It lets us know where we need to invest our dollars versus, ‘Are there things we need to upgrade or replace?’” Payne-Kirchmeier said.

It’s all about the real estate

Despite the potential options, planning for long-term housing ultimately comes down to space for new residences.

This year, Alpha Epsilon Pi and Zeta Beta Tau relocated from Lincoln Street to new residences. AEPi is now at 584 Lincoln St. and ZBT at 2303 Sheridan Road. Theta Chi also moved from 572 Lincoln St. to 2309 Sheridan Road, which is within Lindgren House.

The three unoccupied residences, known as “Peanut Row,” could become new housing real estate. Peanut Row will be demolished this summer, but no plans exist for the vacant site yet, said Bonnie Humphrey, director of design and construction for Facilities Management.

Schapiro and other officials have said residence halls could also be developed on the previous property of Roycemore Elementary School, 640 Lincoln St. However, it first must serve as “swing space” for offices and classrooms while Kresge Hall is renovated next year, NU officials said. Similarly, Van Atta said a new residence space must also be created to host students when Foster-Walker is renovated some time in the future.

Even further down the road, University officials may tear down several major residences, including Bobb Hall and Sargent Hall, as part of NU’s broader Campus Framework Plan. Developed in 2009, the strategy outlines construction projects for the next 50 years.

The walk-throughs

From the end of Fall Quarter to Spring Quarter, Ajith, Van Atta and an ASG housing working group surveyed all residence halls and colleges. The group physically walked through every hall to assess potential needs, such as small maintenance repairs, as well as the opinions of students living there.

“When we were walking through with students, it was the small things, like too much furniture or not enough furniture, or how good a shower curtain was,” Ajith said. “Small things that are important to the quality of life … can make a marked difference.”

The walk-throughs included Riel, who said it was valuable to see the residence halls “through the lens of the students.”

The walk-throughs have resulted in minor improvements to housing throughout this academic year. New water-filling stations were installed in Sargent, Foster-Walker and 1835 Hinman over Spring Break, and more effective shower drains were installed in multiple residences.

“Oftentimes the main concerns were the day-to-day lives of students — (a) focus on academics without worrying about whether a washing machine worked or a shower head worked,” Ajith said.

Jim Hurley, associate vice president of budget and planning, said about $15 million per year is spent on capital, which includes dorm renovations. Residence halls are allotted funds every academic year due to frequent renovations and improvements, he said.

An integral part of the walk-throughs was determining a baseline for what students can expect from the University, ASG and residence hall governments for their undergraduate housing experience.

“It’s very random how the housing will be on campus,” said Van Atta, a McCormick junior. “We want to be able to say, ‘Here is what you can expect on housing: overhead lighting.’”

More options for upperclassmen

The Housing Master Plan will present more options for upperclassmen to live on campus, something currently lacking at NU.

One proposed option is University-owned apartment buildings, which would be leased by NU instead of a landlord.

However, affordability also impacts why students choose to live off campus. Purchasing food from a grocery store and splitting rent seems more economical to many students than continuing to live on campus. Van Atta mentioned polling students to determine at what cost they would live on campus as upperclassmen.

For Jacobi Alvarez, living off campus is partly a financial decision. The Communication sophomore said it is “so much cheaper” for her to live off campus because she often cooks her own food and buys her own groceries.

“I am basically able to live off the money my scholarship would have covered for room and board,” she said. “Once I live off campus, I don’t think I would want to move back.”

Part of the reason the plan focuses on upperclassmen housing is because of the increased community and campus involvement they could potentially contribute to campus.

“Once people live off campus, it’s hard for them to stay involved,” Van Atta said. “They have their own circles, they don’t go to Norris that often. Having more people on campus will mean more involvement.”

However, some students have difficult relations with landlords or with Evanston’s over-occupancy ordinance, which forbids more than three unrelated people from living together. University-owned apartment buildings or more options for upperclassmen housing could help, but they are not a complete solution to the rule, said Kevin Harris, ASG’s vice president of community relations.

The Weinberg freshman said the University recognizes upperclassmen housing as a priority but does not believe the creation of apartment-style living will occur in the near future. In the meantime, the University and city officials are discussing increasing the number of unrelated people allowed to live together to four or six.

Although the plan’s proposals could present attractive options for upperclassmen, many students will still prefer living in apartments and houses. Students say they like the freedom and personal responsibility gained from living on their own.

“We shouldn’t try to push everyone on campus,” Harris said. “It is important for us to branch out and have relationships with Evanston residents so it’s not just Evanston here and Northwestern here.”

Beyond facilities: Creating a community feel

In recent years, NU has added residential communities, which include faculty live-ins and are intended to create a more collective living experience for students. Residential communities differ from residential colleges, which group students together based on similar majors or academic interests.

Allison became a residential community last year after it was renovated over the summer, and Elder has two faculty live-ins. Psychology Prof. Renee Engeln-Maddox is the faculty resident at Allison, and Communication Prof. Bill Bleich and SESP Prof. Pam Schuetz live at Elder.

“We have great people living with us,” Riel said. “That’s something we really think make the programs important. We talk to students that come out of Allison or Elder, and they call it a life-changing experience.”

Student feedback on the addition of more residential communities has been largely positive.

Jules Cantor, Allison’s hall government president, said Engeln-Maddox seems part of the community. She hosts munchies and invites students to have dinner with other professors in her apartment.

“Sometimes I’ll go down to breakfast, and Renee and I will eat breakfast together,” said Cantor, a Communication sophomore. “At a school as big as Northwestern, oftentimes you don’t get to know your professors that well in a big classroom, so the opportunity to work with a professor can be really rewarding.”

However, many students are still not a part of the faculty live-in experience. One goal, Riel said, is to increase student involvement in residential community experiences.

Faculty have also expressed interest in connecting more with students outside the classroom, Riel said.

“We want that connection that goes beyond standing behind a lectern,” he said.