The impact of the sequestration on Northwestern’s financial status is currently no more than a guessing game for University officials.

“The buzzword of the day is uncertainty,” Jay Walsh, the University’s vice president for research, said. “It’s just really not totally clear what’s going to happen going forward.”

What is clear is that the sequestration is slated to cut annual biomedical research funding from the National Institutes of Health by 5.1 percent in about seven months, according to a University news release published Feb. 25. The cut comes as part of an $85 billion reduction in federal spending formally enacted by President Barack Obama on Friday.

Despite the cuts in research funding NU is facing, University President Morton Schapiro, who wrote Feb. 18 to the Illinois Congressional delegation about the sequester’s detrimental effects on Illinois’ schools and job market, did not express much concern about it in an interview with The Daily on Thursday.

“Even at a zero sum gain, we’re gonna do fine because we keep taking in a higher percentage,” Schapiro said. “At a negative sum gain, it depends on how negative it is, so even if it shrinks, I don’t expect our totals to fall. We had $508 million last year. No matter what happens, I think we’re still going to do pretty well.”

But the cuts could have a dismal effect on the state of Illinois. At a press conference Friday at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) said the state is the 10th largest recipient of NIH funding and could lose about $38 million in the midst of the sequestration, according to the Associated Press.

According to an analysis by United for Medical Research cited in the Feb. 25 University news release, NIH-funded research provides 14,000 jobs in Illinois, 727 of which could be lost in the face of the sequester.

Walsh said the uncertainty in NU’s financial proceedings stems from the lack of knowledge of which federal grants from the NIH and the National Science Foundation, the University’s major federal funding sources, will be cut most heavily. People within these agencies are given some discretion in how to allocate funds, and the exact time frame for losing research money is also yet to be determined, he said.

“That amount of guidance is yet to come down to us,” Walsh said.

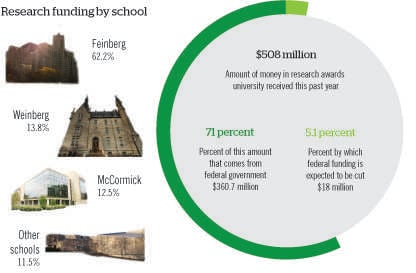

This past year, Walsh said NU received $508 million in awards for research, 71 percent of which was federally funded. A sequester of 5.1 percent out of this 71 percent is anticipated, translating to more than $18 million in funding losses for the University’s research, Walsh said.

In terms of dollar amount, Walsh said the Feinberg School of Medicine is slated to see the most losses of the University’s schools because it receives the most federal research funds. The school received 62.2 percent of the $508 million in funding during NU’s 2012 fiscal year, which spanned from September 2011 to August 2012. Weinberg received 13.8 percent of this funding during fiscal year 2012, while McCormick received 12.5 percent, Walsh said.

Although Walsh said Feinberg will incur the most losses in dollar amount, he said he does not believe any one school in the University will suffer more than another in terms of percentage of monetary loss.

Walsh said it is also currently unknown whether certain grants will be cut entirely or if every grant will be cut partially. He said the University’s approach in dealing with the sequestration will be dependent on this factor.

“There’s no indication by agencies that they’re going to cut whole grants,” he said. “If you have an NIH grant and it got cut by 5 percent, you’re gonna have to figure out how to deal with that. If whole grants get cut or if particular grants get cut a lot, then you have a different approach. Instead of doing less work, you may have to move people around, and that’s really scary.”

Dr. John Friedewald, who teaches at Feinberg and researches biomarkers in kidney transplant patients, said he is not overly concerned with cuts to current grants but about securing more funding in the future. He said the funding will be crucial for advancing his research, which will help facilitate personalized medicine for individual patients.

“Not having money for that may impact patient care — not today, but certainly in the future,” Friedewald said.

Additionally, James Hurley, the University’s associate vice president for budget and planning, said the University’s budget will likely be affected by a reduction in the overhead rate, the money NU gets back from the federal government for every dollar it spends. Currently, Hurley said, this overhead rate is 54 cents for every dollar spent, which helps to fund research.

“If suddenly we’re getting 5 percent less, then that puts a hole in the central budget potentially that we would have to fill through other University sources or cutting expenses,” Hurley said.

This cut may be of detriment to research staff and doctoral students who work in faculty members’ labs, Hurley said, as the federal government often supplies their stipends and tuition remissions.

On a more positive note, financial aid is not expected to take a large hit, according to The White House’s Office of Management and Budget. A document released by the OMB on Feb. 27 did not project a reduction in work-study or Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant allocations to NU.

Even with the uncertainty, the University does have measures it can take in order to lighten the impact of incurred losses. Hurley said Feinberg contains built-in controls that can help the school manage financial setbacks. Additionally, the University can put into practice measures it took to weather the 2008 financial crisis.

“We had lower salary pools, stopped increasing budgets automatically by inflation — every unit of the University came up with a plan to save money and all of those units have stuck with that list of things,” Hurley said. “We delayed capital projects and came back to them when the economy (had) begun to recover. Those are things (administrators will) consider for this sequester.”