Carolyn Murray has worked to strengthen gun control in Evanston for six years. But city efforts to curb Evanston street violence — which claimed three young lives in 90 days in the fall — came too late to save her son.

In July, Murray began plans for Evanston’s first gun buyback program to decrease the number of firearms on the streets, occasionally receiving advice and input from her 19-year-old son, Justin. Just two weeks before the buyback was scheduled, Justin was shot and killed as part of an ongoing gang-related feud.

The elementary school shooting less than a month later in Newtown, Conn., caused national grief and outrage, thrusting the issue of gun control to the public’s attention. But gun violence has plagued Evanston and Cook County for years.

As gun control legislation unfolds on the county, state and national level, Evanston is unlikely to pursue a legislative solution to firearms, instead turning to alternative methods to decrease violence. Evanston Mayor Elizabeth Tisdahl said City Council will not pass laws that could result in an expensive court case. Instead, city government will offer support to larger-scale measures while experimenting with hands-on solutions in Evanston, such as December’s gun buyback program, the city’s first.

In recent months, Cook County has worked to pass progressive gun control measures, including what is likely the country’s first gun or “violence” tax on firearms. Still, gun control activists say strong measures in Cook County aren’t enough; weaker gun laws throughout the country enable the proliferation of gun trafficking into the county.

Murray said an immediate review of gun violence in Evanston is crucial in order to save innocent lives.

“We need to revamp the way we’re looking at violence,” she said. “Otherwise, God help us this summer, God help us for the future.”

Three killed in 90 days

For one of his first assignments of the 2012 school year, Evanston Township High School freshman Dajae Coleman wrote a moving tribute to his family.

“I believe that support from family and friends really helps,” he wrote. “I think the kids that are on the street not doing anything with their lives don’t get the type of support they need from family.”

The 14-year-old wrote about 4:30 a.m. gym workouts with his grandfather, the lessons he learned from his basketball coach and his mother’s constant encouragement for him to never settle.

Just two days after Coleman submitted the essay, he was fatally shot in a tragic case of mistaken identity, marking the city’s first homicide in 2012.

Coleman was killed Sept. 22 in the 1500 block of Church Street as he walked home from a party with friends. Evanston resident Wesley Woodson III, 20, allegedly shot at Coleman because he mistook him for someone else. Woodson, who police say has known gang affiliations, was arrested and charged with Coleman’s murder and is in the midst of trial proceedings.

For the past 12 years, Evanston has had between one and three murders per year, with the notable exception of 2010, when a stunning six homicides occurred in the city. But Tisdahl said even the quantity of the 2010 murders did not affect Evanston in the same way that Coleman’s seemingly random death did. Coleman was remembered by all as a good friend, dedicated student and gifted athlete. His death elicited outpourings of grief and activism from the community.

“People didn’t think, ‘That could be me, that could be my kid.’ People thought those were avoidable,” she said of the 2010 slayings. “Whereas when Dae Dae was killed, nobody thought that was avoidable.”

More than 1,000 people mourned Coleman at his funeral, where Rodney Harris, who spoke for the Coleman family, called for an international “Dae Dae movement.”

“You’ll put your guns down, you’ll put your knives down, you’ll put the malice you have in your heart down,” Harris said.

By the end of September, Tisdahl and various groups had organized forums and meetings to discuss solutions to the violence. Community activists accelerated plans for a gun buyback program in the wake of Coleman’s death.

But for another Evanston teen, the “Dae Dae movement” wasn’t enough. Justin Murray was killed on the evening of Nov. 29 in the 1800 block of Brown Avenue. Evanston police say the death was a result of a long-standing feud between two gang-affiliated families. Justin was home from California to spend time with his family, his mother said.

“He was a very loving son,” Carolyn Murray said. “Anybody that was in need, he always helped them.”

The violence surrounding the feud continued the morning of Justin’s funeral, Dec. 8, when a 20-year-old man was shot multiple times — but not killed — on Howard Street, in what police believe was retaliation for Coleman’s murder.

Just days later, 23-year-old Javar Bamberg was shot fatally in the head Dec. 12 in the 1700 block of Grey Avenue. The investigations surrounding Murray’s and Bamberg’s homicides are ongoing, in part because not all witnesses are cooperating, EPD Cmdr. Jay Parrott said. Police are confident, however, that Murray and Bamberg died as a result of a disagreement between the Bambergs and another local family. The conflict, which has claimed four lives, dates back to at least 2005.

Buying back weapons

Arrangements for the gun buyback — spearheaded by Carolyn Murray — were fast-tracked after Coleman’s murder. The city, in partnership with the Evanston Community Foundation, began fundraising for what has traditionally been regarded as an expensive way to get guns off of the streets. In total, organizers raised $19,050, including a $10,000 donation from Northwestern.

University President Morton Schapiro told The Daily in November that although he was unfamiliar with the success rates of buyback programs, the University was happy to contribute to the effort.

“I don’t know much about buybacks,” he said. “I’ve seen things that (suggest) they don’t work that well, but maybe this one will work better.”

Colleen Daley, executive director of the Illinois Council Against Handgun Violence, said gun buybacks generally have a mixed success rate. She said when Chicago hosted a gun buyback in June 2012, the Illinois State Rifle Association “tried to make a joke out of it” by turning in rusty, unusable firearms for money. However, she maintained buybacks nonetheless reduce the number of guns on the street.

The Evanston buyback, held Dec. 15, fell short of organizers’ expectations. The event garnered 45 firearms in total, including 26 handguns, 15 rifles and four shotguns. Prior to the buyback, police estimated that between 100 and 200 firearms would be acquired. The city spent $4,500 on the program — leaving the majority of the funds untouched as officials decide what to do with them, according to Tisdahl.

Parrott described the buyback as “successful” but said there are “plans for us to do a different type of system” in the future.

Gangs ‘still a presence’

The lethal combination of gangs and guns has caused much of the violent crime in Evanston’s history. Evanston gangs, which Parrott said are distinct from those in Chicago, often develop based on geographic location: A large group may have smaller factions based on members’ neighborhoods. As most Evanston teenagers attend the same high school, gangs can form because “everybody knows everybody,” Parrott said.

Gangs have had a presence in Evanston since the 1970s, Parrott said, although membership has decreased since a peak in the late 1980s. Today’s Evanston gangs are less organized and split into smaller factions than their predecessors. Many street gangs, he said, fund their activities through narcotics trafficking.

Illegal drug dealing has a “direct link” to “violent crime within criminal organizations,” according to the EPD’s 2011 annual report. Parrott said technology had dramatically changed the way gangs in Evanston operate, as the advent of technology has allowed groups to traffic drugs in a more covert manner.

“The days of standing out on the street corner selling drugs are not prevalent in Evanston,” Parrott said. “There’s still a presence; it’s just not as visible.”

Along with the decrease in gang membership, incidents involving handguns have decreased dramatically from 137 incidents in 2007 to just 77 in 2011, according to the annual report. Despite the decline in both gangs and gun violence, Parrott said the two factors still need addressing: The three Evanston homicides this year were all gang-related and committed using guns. Parrott said semiautomatic handguns are used most prevalently in Evanston gun crimes.

Although gangs access firearms through a variety of methods, straw purchasers — individuals without criminal backgrounds who are legally allowed to purchase firearms — have supplied the groups for decades.

Straw purchases allow legal gun owners to purchase guns and then distribute them through private sales. Though gun owners are technically required to keep records of a private sale, many straw purchasers forgo this requirement. When guns end up in crime scenes and are traced to their original, legal owner, the straw purchaser can claim that the firearm was simply stolen.

“Say they buy one (gun) one month, then three months later the same person buys another gun, and he’s got three or four or five different individuals doing this,” Parrott explained. “(This) makes it very hard to trace, especially if they’re different addresses, different names.”

Daley said loopholes like these allow guns to move from legal purchasers to crime scenes.

“Every gun has to start legal somehow,” she said. “That’s the reason why we need strong gun control laws.”

In November, the Cook County Board passed a resolution urging the Illinois General Assembly to pass a “lost and stolen” law, which would require firearm owners within Illinois to report a firearm that has been lost, stolen, destroyed or transferred to state police within 48 hours. The board will vote on its own, local lost and stolen ordinance next month.

Illinois gun laws: Strong or weak?

Despite the prevalence of gun-related homicides in the last year, Illinois has some of the toughest firearm legislation in the country. In 2012, there were 634 homicides in Cook County, 535 caused by firearms. The Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence ranks Illinois eighth out of the 50 states in terms of gun law strength, and Illinois is the only state that prohibits citizens from carrying concealed handguns in public. Parrott said this was a measure of critical importance.

“Allowing people to carry guns is not a step in the right direction,” he said.

In addition, all residents of Illinois who wish to own a firearm must apply for Firearm Owner’s Identification card, a process that requires a background check. Although gun owners must have FOIDs, individual firearms do not need to be registered.

However, Lindsay Nichols, an attorney for the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, said Illinois gun laws are only strict when compared to the nation’s generally weak gun laws. She noted weak laws in states surrounding Illinois make it easy for guns to be trafficked into the state.

“Illinois suffers because of weak gun laws in other states,” she said.

Evanston took its most significant action to deter violence in 1982, when it followed Chicago’s example by passing a handgun ban within Evanston. The ban was overturned in the wake of the 2008 Supreme Court decision that ruled handgun bans unconstitutional Tisdahl said because of that precedent, she will not pass any legislation that would cost the city significant legal fees in court. Still, on Thursday, she publicly announced her support for U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein’s Assault Weapons Bill, which would ban assault weapons and high-capacity ammunition magazines.

In November, the Cook County Board passed its 2013 budget, including a gun tax that will add a charge of $25 to every firearm sold in Cook County. This “violence tax” is likely the first of its kind in the country and will go into effect on April 1. The tax was co-sponsored by Commissioner Larry Suffredin, who represents the 13th district, which includes Evanston. Suffredin has proven to be a strong advocate for gun control in Cook County and Evanston.

The budget also included $2 million toward violence prevention, intervention and reduction groups. Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle on Jan. 22 named the members of the violence advisory committee, which will be responsible for distributing the funds to anti-violence groups and targeting straw purchasers. The board most recently passed another resolution urging the assembly to pass legislation that would ban assault weapons, require the registration of firearms and mandate background checks in firearms sales at gun shows.

Several bills pending discussion in the Illinois General Assembly would comply with the board’s resolution. Legislation introduced recently by state Sen. Antonio Munoz (D-Chicago) and state Rep. Edward Acevedo (D-Chicago) would limit the sale of assault weapons and increase penalties for straw purchasers, among other restrictions.

Illinois’ deliberations coincide with national conversations about which measures will do the most to decrease gun violence. U.S. Sen. Mark Kirk (R-Ill.) is working on legislation that would deter gun trafficking and increase the rigor of background checks.

Changing the conversation

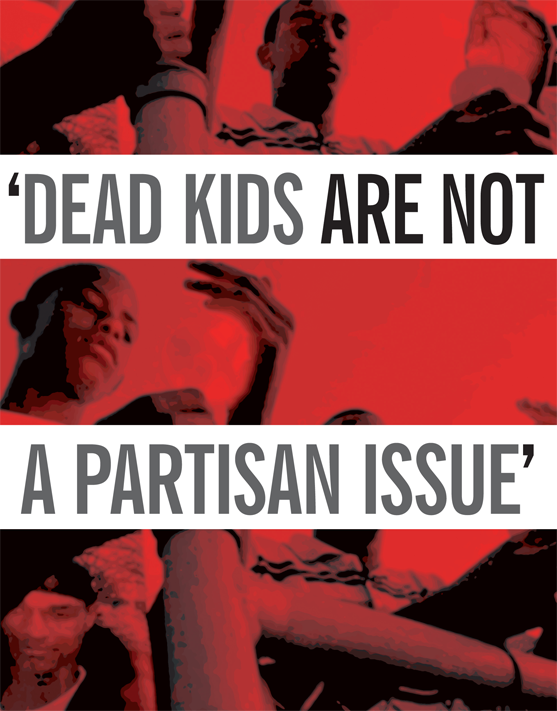

The gun control debate is not just a city issue: It reached the Northwestern campus last week, with the Associated Student Government debating whether to pass a resolution supporting President Barack Obama’s gun control plans. Senators also discussed the possible creation of a committee responsible for writing a letter to Congress to encourage gun control legislation. These proposals have sparked contention among students, including College Republicans members, who believe gun control is a national, politically-charged issue outside of ASG’s domain. Tisdahl, however, chided those who objected to the ASG resolution.

“Dead kids are not a partisan issue,” she said.

As students on campus and legislators across the country deliberate over the best methods to decrease gun violence, those who have been affected most strongly in Evanston believe there needs to be a comprehensive change in the way the city addresses gun violence.

Carolyn Murray said her son’s death has pushed her to work harder to find a resolution to gun violence in Evanston. She called upon the EPD and the city to find new solutions and create a strategic plan to address the violence.

“We have to do a serious makeover on how we’re combating this problem,” she said.