In September 2022, married couple William Soler and Yohana Cabrera arrived in Evanston with their two sons. Their family sought refuge after receiving kidnapping and death threats from a drug cartel in their hometown of Bogotá, Colombia.

Upon arrival, the family of four found a lack of resources in the wealthy Chicago suburb. The few city-sponsored resources were both unhelpful and poorly advertised, they said.

William Soler said he felt lost because the family arrived to a different and harsher reality than they had expected. The family arrived in a declared sanctuary city with little to no structure.

The family said they received little to no aid from the city of Evanston in accessing housing, public school enrollment, food, financial relief or legal consultation throughout their asylum process.

“Without social security and a work permit, which requires time,” William Soler said, “What does one live off of?”

Cities across the U.S. partner with a number of public and private agencies to provide aid, sometimes called “wrap-around services,” to help refugee families acclimate to a new environment. Under this system, legal agencies, medical agencies and social workers collaborate to help families –– a structure that isn’t available in Evanston.

Instead of leaning on the city government, William Soler said his family had to rely on the generosity of community members and neighbors who guided and housed them for more than nine months. The Solers are now one of few known asylum-seeking families residing in Evanston, according to local community organizations and activists.

Some city officials agree that Evanston provides limited aid for refugee families. Ald. Juan Geracaris (9th) said he recognizes the imminent need for wrap-around services in Evanston, especially following the arrival of more than six thousand migrants to the Chicago area in the past year.

“I feel like it’s almost like a failing of our system that we don’t have a way to put these folks in stable housing and get them on their feet,” Geracaris said. “All these folks want to just start their lives.”

The Soler family’s journey to Evanston

William Soler said his brother is a member of the Colombian anti-terrorism national unit GAULA. The unit investigates local narcotics groups violently threatening domestic communities.

One narcotics group obtained a list of GAULA officers, which contained William Soler’s brother’s name.

He said the group began to track the daily routines of every Soler family member, including 7-year-old Jeronimo Soler. The group threatened to murder every family member if they didn’t expose William Soler’s brother’s location.

William Soler and Cabrera said they decided to flee Colombia immediately after receiving those death threats. The couple had high-earning administrative jobs and comfortable lives before they were forced to uproot their family.

William Soler said the family had no option besides an immediate escape, but were not prepared for the emotional, physical and financial toll of the journey to safety.

“We knew there was a possibility that we would be returned back to Colombia at the border. But for us, returning was not an option,” he said. “For us to return to Colombia is to be dead.”

William Soler said the most painful moment for him to recall is when the U.S. border patrol caught the family crossing in between the border walls of Tijuana and San Diego in early September of 2022.

“When I saw my son Jeronimo lifting his hands (to the border patrol officer), it was very emotionally strong for me,” William Soler said. “I couldn’t contain it and began to cry.”

Cabrera said his family was treated “like prisoners” at the border, and each member was stripped of their belongings and documents.

U.S. border control then subjected them to the “torturous” conditions of a densely-packed detention center, William Soler said. With little room to lie down, sleep or move, he said conditions were beyond unsanitary.

Under bright lights in the detention center that were always left on, he added he had nothing to eat or drink for two days other than an orange, one sandwich and one water bottle per person.

Cabrera added it is especially difficult for her to look back on the moment when U.S. border officials at the detention center separated her son Nicholas Soler, then 18, from the rest of the family. The other family members were released after two days of detainment, but officials detained Nicholas Soler for an extra day.

Immigration authorities separated Nicholas Soler’s asylum case from his family members’, placing only him on parole. Now, Nicholas Soler must photograph himself in a previously agreed upon location in the U.S. every Tuesday and upload it to an app on his phone.

The family’s immigration attorney, Emily Love, said the separate processing is a “legal technicality.” Still, she said she presented the asylum case as a family unit, beginning the process at their first deportation hearing last month. Love added she filed the family’s asylum application on that date.

Cabrera said she remembers Jeronimo Soler couldn’t stop crying as he watched officials separate his older brother from the rest of the family. He didn’t understand what was happening, she said.

“Le parte el alma a uno como papá al ver a los niños así,” Cabrera said.

After the Soler family was released, a San Diego non-profit helped the family contact immigration authorities to locate Nicholas. The organization also provided temporary housing and resources — including the family’s first shower in four days.

Nicholas Soler finally reunited with his family on a bus headed to San Diego International Airport days later.

But, the family said their fear of uncertainty persisted as they landed at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago from San Diego, and that feeling continued into that night as they arrived in Evanston — what could become their permanent home.

A ‘pilot family’ hoping to stay in Evanston

William Soler said Evanston neighbors refer to his family as a “pilot family” since they are one of the first widely known refugee families to put down roots in the city. Given rising housing prices, it’s difficult for low income families to stay in the area permanently, according to Geracaris, the 9th Ward councilmember.

According to real estate company Redfin, the median sale price of a single family home in Evanston has risen from $675,000 to $713,500 over the past five years.

Soler said his family would like to settle in the city permanently, given the opportunity.

Lincoln Elementary School ESL teacher Huong Banh said refugee families she has worked with often quietly leave Evanston. She said almost all the refugee children she helps settle into school have to start over in a new city because of the lack of resources in Evanston.

From the dozens of refugee families whose children she has worked with in the past five years, Banh said she knows of only one family who found permanent housing and stayed in Evanston.

She said the family, who had fled Syria, was able to secure housing after Banh and others helped the father find a custodial job at Northwestern. The father then earned enough money to afford an apartment in Evanston, she said.

Banh, who is a migrant, said she sees it as her “personal mission” to help refugee families. After emigrating from Vietnam as an adolescent, Banh began high school in the U.S. without speaking English. She said it’s frustrating to see families arrive in Evanston who need more resources for necessities like housing, legal representation and food than the city provides.

However, Banh said she doesn’t know how to aid refugee families in getting access to more help.

However, Banh said she doesn’t know how to aid refugee families in getting access to more help.

“I can’t do it as a teacher,” Banh said. “We have to have some kind of structure to help the families survive.”

Unlike many others who have immigrated to Evanston, the Soler family found support from residents soon after arriving.

Though they do not speak English, the family said they were able to communicate in Spanish with a Mexican woman who was cleaning the Airbnb they were staying at.

The woman drove the family to Washington Elementary School to enroll Jeronimo Soler. Then Allie Harned, a social worker at the school, introduced the family to City Clerk Stephanie Mendoza, who helped them secure temporary housing.

Jeronimo Soler started at Washington Elementary the next day, Sept. 14, but Evanston Township High School refused to admit Nicholas Soler. According to Cabrera, ETHS Associate Principal of Student Services Mia Lavizzo told her it was because Nicholas Soler had enough credits to receive his diploma from Colombia. Lavizzo declined to comment, citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, which protects the privacy of student education records.

Cabrera said she saw ETHS’ decision devastate Nicholas Soler. She fought for him to start school on Nov. 1, 2022 and succeeded.

Harned said she believes ETHS’ initial decision to deny Nicholas Soler’s enrollment violated the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, which protects the right of all K-12 students to attend school — even if they do not have housing or typically required documentation, including permanent resident status or a U.S. passport. ETHS declined to comment, also citing FERPA.

As part of the act, public schools receive state funds with which they must provide free transportation to school for students in need. BriteLift transportation, a regional company contracted with Evanston/Skokie School District 65, drove Jeronimo Soler to school, according to Harned.

Harned is also District 65’s Homeless Assistance Act liaison. Every local education agency must designate an employee to carry out the law’s provisions, which help ensure houseless children and youth are enrolled in school.

According to the Homeless Students Bill, which passed in Illinois in 2017, state funds that would be directed toward transportation for houseless students can also be used to house a family.

After years of fighting to utilize the bill in Evanston to alleviate the houseless problem created by increasing rents, Harned said the district finally housed a family this year. The family — who began couch surfing when the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020 — was on a waiting list for a city housing voucher for seven years and used money from the Homeless Students Bill to secure it.

“Housing stability will make educational stability more of a thing,” Harned said.

The Soler family’s asylum application has now been filed, beginning a years-long legal process. The family is paying for this process using the majority of their savings — the equivalent of 15 months of William Soler and Cabrera’s salary earned in Bogotá.

Nicholas Soler graduated from ETHS in May, and his family is determined to find money to send him to Oakton Community College. Without asylum, he is not eligible to receive federal student aid.

NU biology Prof. Marcelo Vinces advocates for support and resources for undocumented Northwestern students as club adviser of the University’s Advancement for the Undocumented Community club. Vinces, who comes from an undocumented family, said applying for multiple scholarships — including several designed specifically to help undocumented students — is the only way for refugee students, such as Nicholas Soler, who don’t qualify for federal aid, to attend university.

“That’s the way (these families) put together a financial aid package,” Vinces said. “Which is so much more work and burdensome than someone with a legal status going through the (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) form.”

Since Illinois describes itself as the “most welcoming state in the nation” with immigrant-friendly policies, undocumented students can be eligible to pay in-state tuition rates at state universities. But these rates still represent thousands of dollars many refugee families don’t have.

Often, state-funded resources are not enough for families to permanently settle down and pursue higher education, Vinces said.

Finding a place to live

Though the family managed to enroll their children in Evanston public schools, they said finding housing was more difficult.

After living in an Airbnb for a few days, the Soler family stayed at a hotel for two nights. Mendoza then reached back out to offer them temporary housing with her mother. The family lived there for about two weeks.

“My family immigrated here (from Mexico),” Mendoza said. “When something is so … deeply personal, you just find a way to help.”

In the past, Mendoza has helped connect other recently arrived migrant families to health care and essential resources provided by local organizations like Refugee Community Connection and individual community members, she said.

Mendoza added she could not sit idly by while the Soler family needed help, and wanted to become the kind of helpful figure she wished her parents had when they settled in Chicago.

“We’re all just a piece in the puzzle,” Mendoza said. “We can connect this family (to resources) to just make these people whole.”

Cabrera said during the family’s time in Evanston, they have not received any official government aid from the city. Mendoza helped the family through personal connections — instead of in her official capacity as city clerk.

While searching for housing for the Solers, Mendoza eventually introduced the family to a resident with a vacant property through that resident’s councilmember: Ald. Eleanor Revelle (7th).

At that time, resident Susan Besson was navigating her own hardship, having recently lost her husband to cancer. She said she told Revelle she wanted to use the apartment where her husband had lived to house a family in need. Revelle heard Mendoza mention the Soler family’s housing situation at a City Council meeting and contacted Besson soon afterward.

After meeting the Solers, Besson immediately offered to house the family.

“My story is kind of ridiculous,” Besson said. “It’s like a message in a bottle. I just tossed this thing out into the universe, and then they showed up … They feel like family to me”

The family said they moved into the upstairs unit of Besson’s two-apartment flat the day after meeting her. They have lived there since.

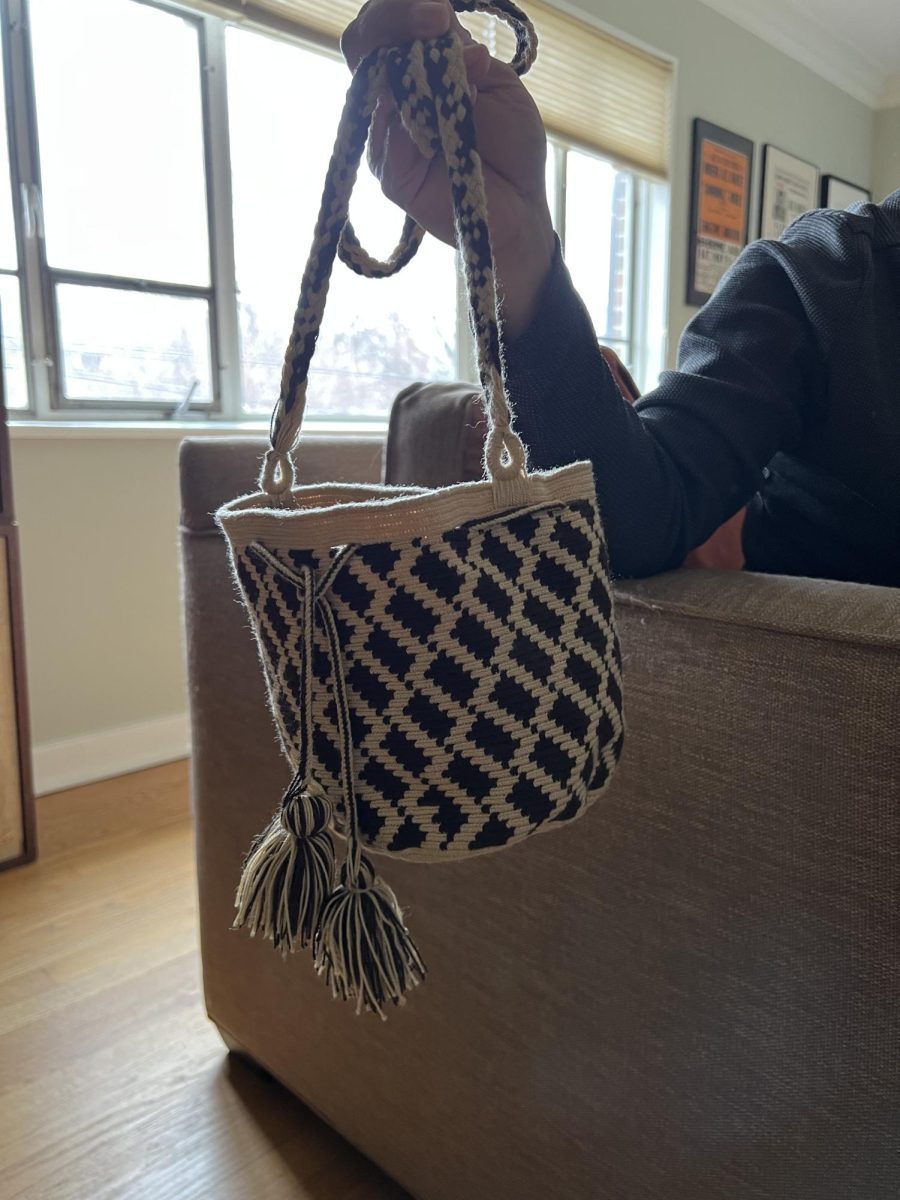

William Soler gifted Besson a woven Wayuu bag—traditionally made in Colombia by indigenous artisans—even before she offered her home to them. He kept the item with him throughout his lengthy journey from Bogotá to Mexico City to Tijuana, and then San Diego to Evanston.

Besson said she was elated to offer her home to a family in need, especially given Evanston’s limited housing options.

“In spirit, Evanston is a welcoming community,” she said. “But … there’s not really an infrastructure to welcome, house and guide these people.”

Besson added the city needs to create a systemic approach to help refugees, especially with housing.

In the missing welcoming infrastructure, housing is the most prominent factor.

“The housing piece is probably the most difficult. And, unfortunately, (the city doesn’t) have any way of providing that housing,” Geracaris said.

RCC is an organization that supports migrant communities seeking refuge in Chicago. Nan Warshaw, the group’s co-founder, said it’s crucial to find more housing solutions for migrants and refugees, especially in Chicago.

Warshaw said she co-founded RCC in 2017 to encourage people to be more compassionate toward and assist refugees in the area. By the end of 2021, RCC’s Facebook group had around 3,000 members. Today, the organization has more than 7,500 group members and thousands of volunteers.

As of May 2023, RCC has assisted 318 households in finding permanent housing and connected thousands more to temporary housing solutions like shelters, rest centers and police stations.

Chicago is struggling to welcome more than 8,000 migrants who have arrived in buses from the southern border since April 2022. Warshaw said the city is also expecting more arrivals after President Joe Biden lifted Title 42 in May, a holdover from former President Donald Trump’s administration that allowed border officials to turn away migrants on the basis of COVID-19.

Typically, migrants wait around a week in Chicago police stations before they are able to receive temporary housing, Warshaw said. She added RCC volunteers have received messages from malnourished migrants based in crowded Chicago shelters who were forced to sleep on the floor.

The Chicago Police Department and Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson did not respond to The Daily’s request for comment.

“We really need the city, state and federal government to step up and provide a comprehensive plan … and help (migrants) transition to permanent housing,” Warshaw said.

After Chicago, Evanston has the most RCC volunteers and donors of any municipality in the Chicago area. The organization is primarily trying to help refugees who live in South and Downtown Evanston. However, RCC can only consistently connect with those who have secured permanent housing since it is difficult to account for those with unstable housing.

RCC routinely provides resources ranging from clothes to feminine products to kitchen utensils to toys for migrants, but cannot guarantee housing due to resource constraints.

“(Refugees rent) an apartment, but then that exhausts all their savings, and then they don’t have money for furniture, clothing and other things,” Warshaw said.

Most refugees RCC helps are visa holders who acquire temporary federal work permits in the U.S. within a few weeks of arriving. However, federal law mandates that asylum seekers wait 150 days from the day they apply for asylum before they are eligible to apply for a temporary work permit.

The Soler family began their six-month asylum application process during their first hearing in May. Cabrera said they will apply for a temporary work permit in October — more than a year after they arrived in Evanston.

The family said they were unaware of RCC when they first arrived in Evanston, so they never reached out or received any aid from the organization.

Refugees typically only find out about RCC by “word of mouth” in a city where it is already difficult to reach out for help, Warshaw said.

According to Warshaw, 14 refugee households moved into apartments in Evanston in 2022. As of May, only two families had moved in this year.

“Word is out in Chicago, but what do you do in Evanston?” Warshaw said.

She added RCC does not work with Evanston directly and is unaware of any resources the city may provide migrants.

Warshaw said she only hears of residents taking it upon themselves to assist and welcome families. She said many residents support the families by volunteering in RCC’s funded welcome group program, through which more than 200 groups have helped more than 255 households in the Chicago area since 2021.

Limited funding from Evanston

Options paid for by Evanston’s city government for refugees are limited, Geracaris said. He said the primary way the city can help migrant families is by partnering with refugee organizations to facilitate aid.

In October 2022, City Council created the Refugee Resettlement Fund after allocating $50,000 from money Evanston received from the American Rescue Plan Act. The fund aims to provide families who have fled violence and persecution with services like clothing, food and transportation by contracting with external organizations.

Director of Health and Human Services Ikenga Ogbo said money for the fund is the only way the city of Evanston aids refugees directly.

Ogbo added the city works with other refugee aid organizations, including Family Focus and RefugeeOne, to provide resources to refugee households.

“We can’t do it alone,” said Ogbo. “This is pretty much an all-hands on-deck affair.”

From the end of November 2022 to the beginning of March 2023, the fund financed nearly $14,000 of housing, food, clothing, transportation, and other necessities for migrants, according to city documents.

The four month-long program allocated 14 people less than one thousand dollars worth of resources each.

Geracaris said the city needs to better advertise the fund — which both Banh and the Soler family said they did not know existed — and begin contributing a greater amount of money annually. The fund is not currently set to be renewed after the initial $50,000 is fully spent.

During a 18-month refugee surge from 2021 to 2022, RCC provided $1,378,094 worth of household items — not including large furniture donations — to resettle people, according to an estimate Warshaw provided to The Daily. The estimate accounted for the value of in-kind donations, which are contributions that are not cash, such as assets like clothes or feminine products.

Throughout this calendar year, she estimates RCC will provide refugee families with approximately $2 million worth of donations, including cash intended for the immediate purchase of items like electronics.

A new welcome center

Geracaris said the resettlement fund is not all that’s needed: refugees need more guidance from the city about what resources are available to them.

Family Focus, for example, soft-launched some welcome programs for immigrants and refugees in January. The organization, which doesn’t solely serve refugees and migrants, provides holistic support to families and children enrolled in its programming.

In October 2022, the city approved $500,000 in ARPA funds to help Family Focus build and launch a brick-and-mortar welcome center. The city has also allocated $3 million from ARPA funds to renovate the former 5th Ward Foster School, which will house the center.

William Soler said his family attempted to receive help from Family Focus, but the organization put them on a six-month waiting list. They never heard back.

Mariana Osoria, senior vice president of partnerships and engagement at Family Focus, said there are four main ways Evanston’s welcome center will provide newly-arrived families with essential wrap-around services: providing services directly, connecting families to other relevant organizations, hosting educational workshops and working with community alliances that identify immigrants’ needs.

The center is currently in a “soft open” phase, Osoria said. It has hired and trained staff, and hosts meetings with community alliances.

Since its soft-launch, the center has provided housing assistance to five migrant families. It has also helped the families find legal support, connect with school resources and complete Illinois’ emergency funding applications.

The emergency funds are part of a state initiative to support undocumented migrants who lacked financial support during the COVID-19 pandemic. The funds award up to $2,000 per adult and $500 per child, according to Osoria.

While the welcome center originally planned to open in January 2023, it has yet to open its doors.

Family Focus had been interested in providing more resources for refugees in Evanston for at least a couple of years, Osoria said. However, City Council and Evanston Latine leadership convinced Family Focus that Evanston had the right need and opportunity to build the project two years ago.

Mendoza and Geracaris advocated for the welcome center as members of Evanston Latinos, an organization that promotes equity and inclusion for the local immigrant and Latine community. Mendoza said she was “extremely proud” when City Council passed funding to open the center unanimously in October.

Osoria said without advocacy and commitment from the community — and specifically Latine leaders — Evanston would not have a welcome center. She hopes the center is the first step in Evanston’s efforts to create a cohesive system for all recently arrived refugees and immigrants, she added.

Rather than having families’ opportunities to succeed be defined by chance, the systemic approach attempts to provide equitable access to all resources.

Harned added she has been working on Evanston’s Mental Health Task Force, which is focused on creating a wrap-around service system in Evanston. The task force aims to address issues with the city’s current method of providing resources to residents in need.

She said she is seeking funding from the city to invest in a case management software system. Key to wrap-around services in other cities, systems like these hold a family’s file in one place and allow all agencies to access it, which increases efficiency.

“The city is working really hard, there’s no doubt about that,” Harned said. “It’s a matter of getting people connected to that in order to tap into those resources, but then there’s gaps between them.”

The gaps between refugees and available resources makes all the difference to families who have given up everything to find safety.

With a wrap-around services system in Evanston, migrant families would only have to tell their story one time, Harned said. They could get the help they need without walking through a series of misleading doors, she added.

“We live, we get up and we do our day to day life but (the traumatic memories of our journey here) are right there,” William Soler said. “If I would have known that my kids would go through that, I think, I don’t know where I would go, but I know not here.”

Email: marthacontreras2025@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @marthacontrerr

Related Stories:

— City Council allocates funds for welcoming center

— Illinois workers no longer excluded from EIC tax relief due to age or immigration status