‘Activism is part of everyday living’: Bursar’s Office Takeover participants reflect on protest, careers

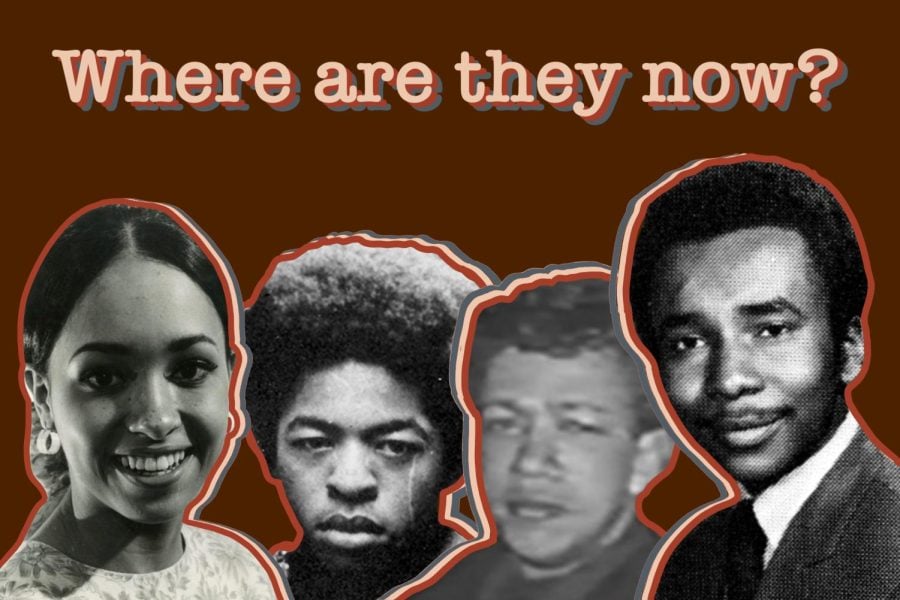

Those who participated in the Takeover have taken different career paths, ranging from music to legal professions.

May 22, 2023

On May 3, 1968, more than 100 students occupied the Bursar’s Office in a peaceful protest lasting 38 hours. The activists aimed to raise awareness about the lack of academic, housing, counseling and financial resources available for Black students on campus.

By the end of the Takeover, Northwestern administrators agreed to some of the students’ demands, promising to increase Black student enrollment and create the Black House.

Now, 55 years later, student activists continue to reflect on the protest. Some now practice law, while others are musicians. But, regardless of their career trajectories, many protestors say the experience was central to their NU and life experience.

Charles McBride

Charles McBride (Weinberg ’72) was part of a 10-person contingent of students who entered the Bursar’s Office. The team was “on pins and needles” about what was going to happen, he recalled.

The group planned to enter through the revolving doors and open the back door for protesters to come in. Then, the students would chain the doors closed.

Accessing the revolving doors without interception by a security guard presented a challenge, McBride said.

“We planned to have a diversion where some Black students would try to get the attention of the security guard … running around, making a lot of noise,” he said. “That plan worked.”

After graduation, McBride worked as a probation officer at the Cook County Juvenile Court for 25 years.

He felt his impact in the job was “minimal” while working with children. McBride said he found it difficult to maintain his optimism while working within the criminal justice system, he said.

“It seemed there was very little that I could do to make any difference in their lives, because the odds were stacked against them,” McBride said. “If I was able to make a difference in one kid’s life, then I would consider that a success.”

McBride said the Takeover was the first step of his commitment to improve the experiences of Black students.

In 2018, he returned to NU to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Takeover. The visit allowed him to reconnect with fellow activists and look at NU’s progress in response to the original demands, he said.

“(I was) pleasantly surprised to see all the Black faces (and) all the Black students on campus. That was such a big difference from my tenure at Northwestern,” McBride said. “I felt I played a small role in making that possible.”

Stanley Louis Hill Sr.

Stanley Louis Hill Sr. (Medill ’70) said he participated in the Bursar’s Office Takeover because he believed it would make NU a better place for every student. Advocating for the Black experience would benefit students of all cultures, he said.

“It was springtime,” he said. “We needed to do some spring cleaning to improve the community where we live and the school we attended.”

While Hill worked in advertising after graduating, he said the philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr. inspired him to transition to a law career, where he worked as a defense lawyer.

He cited one of King’s most well-known metaphors as his motivation: while a thermometer accepts conditions, the thermostat reexamines and alters the future.

Hill worked as a lawyer for 37 years before the Illinois Supreme Court appointed him to serve as an associate judge on the Cook Judicial Circuit Court in 2010.

Hill emphasized the importance of helping one’s community. He said people can’t “just sit back” to create change — they must work to improve the well-being of others.

“It’s the same motivation that propelled me into participating in the Takeover,” Hill said. “Now, it’s propelling me 54 years later.”

Since the Takeover, the University has hired more Black professors. The wisdom of Black scholars like Margaret Walker and Lerone Bennett Jr. left lasting impressions on him, he said.

Hill represented the class of 1970 at Northwestern’s convocation three years ago. During his remarks, he offered eight lessons, including idioms like “old friendships are pure gold” and “people are precious.”

“Who I am today points back to the strong impressions made and lasting impressions made by everyone I met while at Northwestern,” Hill said.

Daphne Maxwell Reid

For Daphne Maxwell Reid (Weinberg ’70), participating in the Takeover was a “duty.” While growing up, Maxwell Reid’s family consistently participated in civil rights and peace demonstrations.

“My upbringing is what mostly affects how I view things,” Maxwell Reid said. “I come from a family who were activists. My mother never saw a cause she didn’t rally for or against.”

Maxwell Reid sat in the bursar’s office for about two days. When she called her mother during the Takeover, all she said was “let me know if you need any money for bail,” Maxwell Reid recalled.

Today, Maxwell Reid is an actress and best-known for her role as Vivian Banks in NBC’s hit sitcom “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.” Maxwell Reid, who is also a former model, became the first Black woman to don the cover of Glamour while studying at NU — which she said the University didn’t acknowledge at the time.

Maxwell Reid was also NU’s first Black Homecoming Queen, which she described as a “horrible” experience. Nobody was pleased, she said, and the University ignored the fact that she was awarded the honor.

There was no picture or statement in the yearbook acknowledging she was Homecoming Queen, Maxwell Reid said. When she asked the editor why she wasn’t featured, the editor claimed Homecoming wasn’t important, Maxwell Reid recalled.

Maxwell Reid was a member of university boards at NU and Virginia State University, but left both. She said the NU board was not making enough progress toward the goals she envisioned.

“Activism is part of everyday living,” Maxwell Reid said. “Either you’re quiet or not. And I’m not.”

Adegoke Steve Colson

To prepare for the Takeover, Adegoke Steve Colson (Bienen ’73) snuck under the Rebecca Crown Center to locate underground passageways. He helped the demonstrators mark out the location of the Bursar’s Office.

Adegoke Steve Colson said Black students pulled together for the Takeover. The protest required trust because only a few people knew what was going to happen, he said.

“Anybody could have said, ‘I’m not going to do it,’ but the student body was involved,” Adegoke Steve Colson said. “You can’t predict whether you will get people to follow you into something where … you could lose your ability to be a student at the institution.”

In May 2020, Adegoke Steve Colson, who has performed jazz internationally, received a grant from the American Composers Forum, for which he wrote an original piece that premiered at the Logan Center for the Arts. Colson has worked with leading performers like saxophonist David Murray and master poets and activists Amiri and Amina Baraka.

He and his wife Iqua Colson, a singer and educator, maintain their own record label, which keeps them busy, he said.

As the only Black male in his entering class at the Bienen School of Music, Adegoke Steve Colson played piano, saxophone, string bass, trumpet and clarinet while also pursuing a vocal minor.

Though Adegoke Steve Colson studied classical artists, he also practiced jazz in his free time and helped form a jazz band his freshman year.

As a student, Adegoke Steve Colson wanted to explore Chicago’s jazz scene and played with jazz tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson, who lived in Evanston at the time.

“My idea was fairly set by the time I was 15 about what kind of music I liked and what kind of music I wanted to perform,” Adegoke Steve Colson said. “I was listening to jazz when I was young, and I wanted to be a jazz musician.”

Email: jessicama2025@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @JessicaMa2025

Related Stories:

— Daphne Maxwell Reid: from homecoming queen, to the set of ‘Fresh Prince’

— Protesters demonstrate against on-campus policing, present Black student demands at The Rock

— “Black House is back”: 1914 Sheridan Rd. reopens after more than two years of renovation