Mitchell Museum’s ‘No Rest’ calls attention to epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women

Aviva Bechky/Daily Senior Staffer

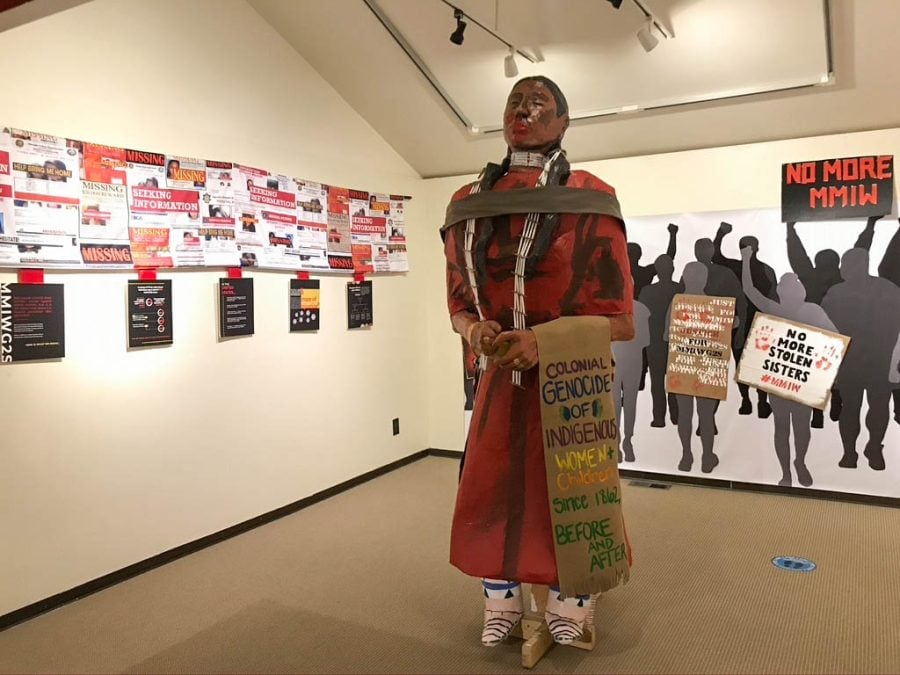

A papier-mache statue in “No Rest: The Epidemic of Stolen Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirits.” The exhibit calls attention to violence against Native women and two-spirit individuals.

March 5, 2023

Content warning: This article contains discussions of violence against Indigenous women.

At the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian’s “No Rest: The Epidemic of Stolen Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirits” exhibit, thousands of red ribbons hang in a curtain, each inked with the word “JUSTICE.”

Valaria Tatera — an artist, lecturer, activist and enrolled member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa — stamped each ribbon by hand. The ribbons will symbolize more than 5,000 missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit people, she said.

“My goal is to have a ribbon for each of the MMIWG2S,” Tatera said. “As new data becomes available, the art piece will grow, creating a living installation.”

Tatera’s piece, titled “Justice,” is one of 35 works by 12 contributing Indigenous artists in “No Rest,” which aims to draw attention to crimes against Native women and two-spirit individuals throughout the U.S. The touring exhibit, curated by the Institute for American Indian Studies, will be open at the museum through September 2023.

Kim Vigue — the museum’s executive director, an enrolled member of the Oneida Nation and descendant of the Menominee Tribe from Wisconsin — said Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women found footing as a grassroots movement in about 2015, and the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women has gained attention since then.

Native American women face more than 10 times the national average murder rate. According to the Mitchell Museum, out of 5,712 reports of missing Indigenous women, only 116 are logged in the U.S. Department of Justice’s missing person database.

But Vigue said those numbers likely underestimate the depths of violence against Native women in the U.S.

“The scale of this is probably much, much worse,” Vigue said. “Because Native people are a small population and we’re sort of invisible to begin with, a lot of times when cities or states and the federal government is gathering data, we get put into an ‘other’ category.”

Dante Biss-Grayson, who is from the Osage Nation and whose work appears in the exhibit, said he hopes to bring more awareness to MMIWG2S.

His works, which are untitled, feature collages of images of missing and murdered Indigenous people. Red and black handprints stand out, and barbed wire criss-crosses the canvases.

“It’s a call to action,” Biss-Grayson said. “The more people that know about this, the more that hopefully we can give these people who have been murdered, give them the justice.”

In addition to viewing the exhibits at the museum, visitors can also tie tobacco into bundles, imbuing them with prayers and well-wishes. The tobacco comes from the museum’s Indigenous Medicine Garden, where the ties will be hung later this year.

The strings of ties already hanging in a doorway inside serve as a visual reminder of community support, Vigue said.

“It really shows that people care and people want to be supportive,” she said. “Even people that weren’t aware of the issue leave wanting to … make a change.”

She encouraged people to contact elected representatives about supporting tribal sovereignty to prosecute crimes against Native women and to share resources to advocate for the MMIW movement.

“There has been momentum over the past few years, but it’s not the end,” Vigue said. “It’s a long process.”

Email: avivabechky2025@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @avivabechky

Related Stories:

— Mitchell Museum of the American Indian hosts 45th Anniversary Benefit and Awards Ceremony

— ‘Connecting with Mother Earth’: Mitchell Museum to host film screening of ‘Inhabitants’

— Meet the three new board members at the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian