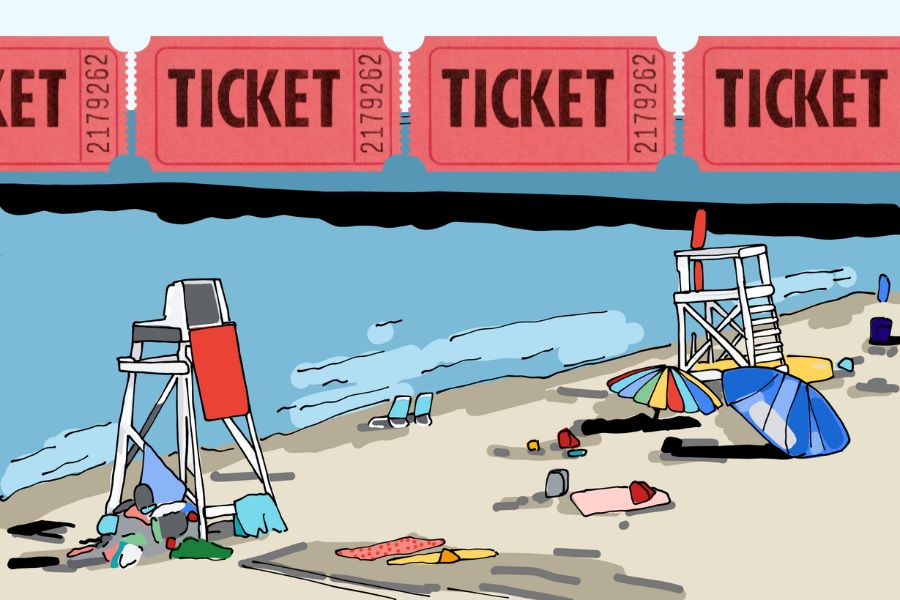

Evanston ends beach token system, makes beaches more financially accessible

This past summer was the first time Evanston beaches have been free to residents since beaches were segregated.

October 18, 2022

As soon as Ald. Devon Reid (8th) was sworn into City Council, he said his number one priority was to make beach passes free for Evanston residents.

It wasn’t just to drive more traffic to the beaches — Reid wanted to end a policy that had long been used to block off the city’s beaches from Black and low-income residents.

“(Making beach passes free for residents) was low-hanging fruit, if you will, for us to begin the process of undoing clearly racist and classist policies here in Evanston,” Reid said.

Ever since residents began using Evanston beaches recreationally in the early 20th century, the city has heavily regulated the beaches. Community members and elected officials have long pointed out how segregated beaches, costly tokens and dress code regulations led to racism, classism and sexism on the beachfront in Evanston throughout the 1900s.

In 2022, Evanston charged $10 per person for non-resident daily passes and between $19 and $62 for non-resident season passes, depending on the time of purchase. Before the new policy began this summer, residents paid $8 for a day pass and $18 to $28 for a season pass.

Now, after the city’s first summer with completely free beach passes for Evanston residents, community members and city staff reflect on the shore’s complicated history — and the impacts it still has on beach access.

A history of inequity

Evanston beaches were segregated until 1931 when Evanston’s first Black alderperson, Edwin B. Jourdain, Jr., pushed to end beach segregation. Reid said Jourdain’s colleagues responded by designating some beaches as free, while charging residents at others.

“They said, ‘We’ll have the free beaches, which were meant to be the de facto segregated Black beaches, and then we’ll have the beaches that we charge access to, under the guise of beautification, and those will be the white-only beaches,’” Reid said.

The city began using beach tokens for its paid beaches, funding a “beachfront beautification program.” Reid and others said the tokens were really meant to impose a cost barrier to keep Black residents from accessing white beaches, prompting public outcry.

“Beautifying” the beach also played into tensions along the shoreline, according to Jenny Thompson, director of education at the Evanston History Center.

“We’ve evolved into now thinking of these (beaches) as these pristine recreational spaces, but they’re so connected to the larger cultures,” Thompson said.

In 2021, Thompson published “A Shifting Shoreline,” a research piece detailing the history of social conflicts along Evanston’s shore in the Evanston RoundTable. She said many of Evanston’s beaches in the 19th century were used to dump trash and wastewater, according to her research.

As residents began to use the beaches recreationally, she said the city saw more cleanup efforts, used as an avenue for increased city regulation on the beaches.

Though the beaches were eventually desegregated, Thompson said this created a unique intersection of racial, economic and environmental tensions.

“Even though they’re natural spaces, they’re really shaped by human behavior,” she said.

Today’s policy

In May 2021, City Council voted to make beaches free for Evanston residents on Saturdays, Sundays and Mondays. Though Reid advocated for making them completely free in the 2021 season, others cited concerns about the impacts of cutting a major source of city income in the middle of the fiscal year.

The city ultimately decided to work toward phasing out beach tokens, and in 2022, Evanston residents could visit the beaches for free all summer long.

Community Alliance for Better Government board member Sebastian Nalls said no-cost access allows working families to enjoy the beach.

“It gives flexibility to folks who feel that making that full purchase commitment is too much for their family because they don’t know how often they’ll go,” Nalls said.

The May 2021 decision followed years of advocacy by groups like Evanston Fight for Black Lives. The organization started a petition to get rid of beach tokens, citing the cost barrier and racist history of the tokens.

Nalls said he saw the tangible effects of the end of the token program this summer.

“When I went to the beaches, I saw a more diverse group of folks that were going and that was something that we saw during the previous summer.” Nalls said. “(On) the free beach days that were available to residents, those tended to be the most diverse crowds.”

Reid said free beach access could attract more traffic downtown, driving city revenue through parking rates and sales taxes that could fill the potential fiscal gap left from beach pass costs.

Though Reid said the city has reached a “nice stasis” on beach pass policy, he emphasized that addressing Evanston’s lakefront history is an ongoing process.

“My philosophy is, (this history) reconfirms the idea that racism and classism are extremely intertwined,” Reid said. “In order to combat one, we need to combat both.”

Email: shannontyler2025@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @shannonmatyler

Email: lilycarey2025@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @LilyLCarey

Related Stories:

— How Evanston’s beach tokens create an access barrier to Lake Michigan

— Evanston to offer three free weekly beach days after advocacy against token sales