Northwestern researchers develop sponge to clean oil spills

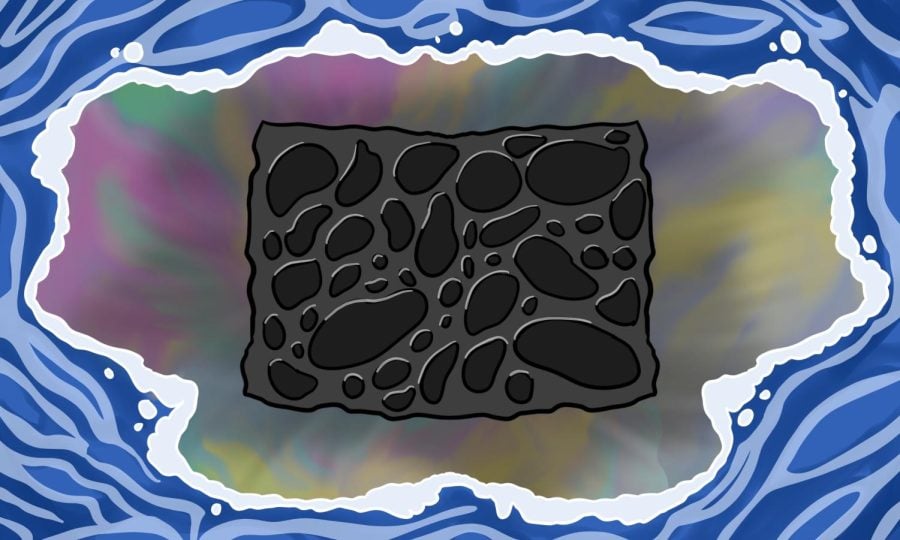

Northwestern researchers are working on sponges designed to clean up oil spills.

May 9, 2022

Sponges similar to an ordinary kitchen or memory foam sponge may soon clean up oil spills, courtesy of Northwestern researchers.

The environmental subgroup of McCormick Prof. Vinayak Dravid’s lab is developing sponges capable of absorbing oil and pollutants like phosphate, micro- and nanoplastics and heavy metals from water.

“It’s like a Swiss army knife, we call it, for environmental remediation,” Dravid said. “We have solutions for different problems, and all we do is mix and match.”

Dravid said the project follows “the story of R”: repurposing sponges, reducing waste, removing and recovering pollutants, reusing the sponge and restoring the environment.

Furthest in development is the OHM sponge, an abbreviation for oleophilic, hydrophobic and multi-functional. The sponge can hold up to almost 30 times its weight in oil, according to Dravid, and can be wrung out like a kitchen sponge. The oil can be released by sending electromagnetic waves at a radio frequency through the sponge.

McCormick Prof. Vikas Nandwana, who works in Dravid’s lab, said current methods of cleaning oil spills — like breaking down the oil with chemicals — hurt the environment.

“Either they generate a lot of physical waste, which goes to landfill, or they generate a lot of carbon footprints,” Nandwana said. “We were looking for a solution which is very clean. And not only clean, but also economic and scalable, something that does not disturb marine life.”

Sponges are reusable, cheap and plentiful — and the lab can source sponges that would otherwise end up in landfills, Dravid said. Because of their high surface area to volume ratio, sponges can absorb oil and other pollutants well.

The lab relies on two types of sponges: polyurethane, which is similar to memory foam, and cellulose, which is similar to a kitchen sponge. The former is hydrophobic and won’t absorb water, but absorbs oil well. Cellulose does absorb water, which makes it more effective for filtering out pollutants mixed with water.

Each sponge is covered in a nanotechnology slurry — a technical term for a combination of very small particles with water. Those particles bind with specific pollutants, allowing the sponge to clean contaminated water by selectively pulling out the pollutants.

“We make (particles) small so that we get large area, but also that process can impart some unusual behavior to the material that we like,” Dravid said.

The carbon used in the OHM sponge repels water better as a nanoparticle, he said.

The lab applies different slurries to sponges intended to pick up different pollutants, but Dravid said he’s hoping to combine multiple within each sponge to pick up several pollutants in different bodies of water. Each pollutant-absorbing sponge has its own mechanism for releasing the pollutant.

The sponges’ versatility inspired the name of his and Nandwana’s start-up: MFNS Tech, short for multifunctional nanostructures.

Nandwana said the demand for the technology is clearly present, especially after recent oil spills like the 2020 spill in Mauritius and 2021 spill in Southern California.

“A lot of groups contacted us… And then they said, ‘Why are (you) not using actually the sponge at the sites?’” Nandwana said.

MFNS Tech is working to get regulation clearance from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which has the most stringent requirements in the country. The OHM sponge is also going through U.S. Environmental Protection Agency testing to make sure the sponge doesn’t leak toxins.

In the meantime, the lab is testing more and more sponges. Stephanie Ribet, a fourth-year material science and engineering Ph.D candidate who works in Dravid’s lab, developed a sponge that can recover phosphate, which is a nonrenewable resource that can cause algae blooms and dead zones in bodies of water. Other graduate student researchers focus on heavy metals like lead, micro- and nanoplastics and even carbon dioxide in the air.

“We’re trying to develop a reusable, economic and environmentally sustainable solution to remediating different types of pollutants from water,” Ribet said.

Email: avivabechky2025@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @avivabechky

Related Stories: