Soaked: How a sponge could clean up oil spills

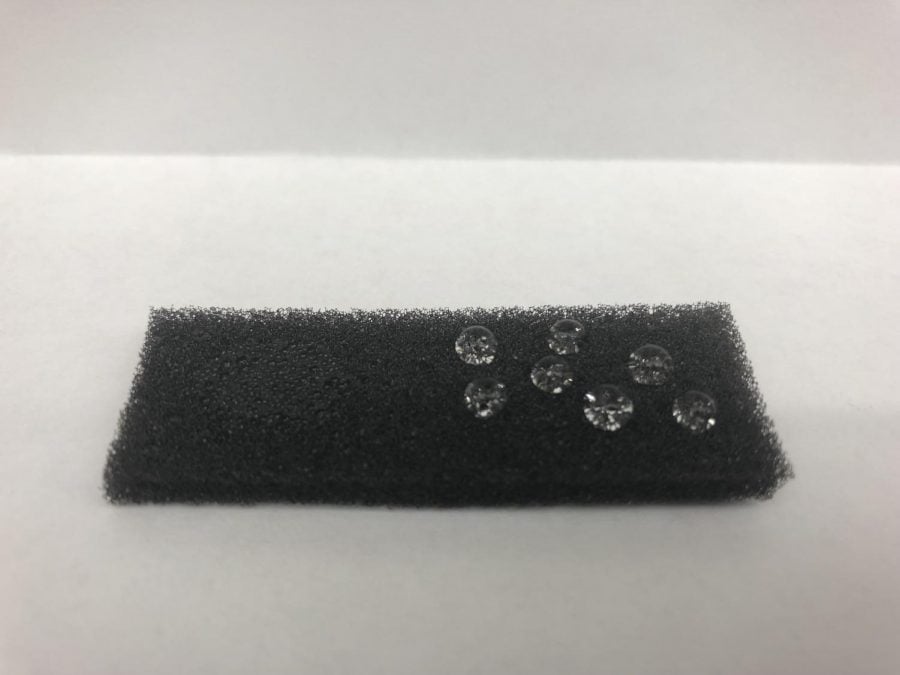

Courtesy of the OHM sponge team

The OHM sponge. The sponge is hydrophobic, meaning it resists water, but oleophilic, meaning it attracts oil.

June 16, 2020

A Northwestern-led team has developed a reusable sponge designed to clean up oil spills.

The OHM sponge can be used dozens of times and can recover oil for future use, according to the research published in Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. The sponge is coated in a nanocomposite slurry, which allows the sponge to attract oil but resist water. It is composed of abundant and inexpensive materials — iron and carbon, according to an email sent from one of the researchers — contributing to the sponge’s relative cost-effectiveness.

The slurry can also be coated onto a commercially available sponge.

Vikas Nandwana, a postdoctoral fellow at NU and an author of this paper, noted that the OHM sponge presents a safer, more environmentally friendly alternative to some other cleaning methods. Such methods include burning oil, which emits carbon; skimmers, which do not work in rough waters; dispersants, which can harm marine wildlife; and sorbents, which are expensive and generate enormous amounts of waste, according to the research.

“What our sponge is doing is taking consideration of the disadvantage of the previous solution and then solves it,” Nandwana said.

McCormick Prof. Vinayak Dravid led the research, working with Nandwana and other team members. He said the sponge developed out of an entirely different area of research: biomedicine.

He said they had been researching nanostructures for MRI and other medical-related use, but with the development of a flow reactor, which allowed for a more large-scale production of nanostructures, as well as keeping open minds for other applications beyond biomedicines, the team had been able to develop the sponge.

“Being aware of what’s going on in other areas is important,” Dravid said. “We were keeping our eyes open, and suddenly the same technology we were looking to cure cancer and Alzheimer’s can be an effective technology for oil spills. That really tells you about the beauty and elegance of science.”

Stephanie Ribet, a Ph.D. student and co-author of the sponge research, is also working to modify the sponge to clean up agricultural pollution.

Ribet said the key difference between cleaning up oil spills and cleaning up agricultural pollution is that most pollutants dissolve in the water, whereas oil and water remain separate when oil spills into bodies of water.

“A nutrient will be dissolved in water, so you actually don’t want something hydrophobic,” Ribet said. “You want something hydrophilic, but you want something with even more affinity for the pollutant you’re trying to absorb.”

Now, Dravid and Nandwana have created a start-up company, MFNS Tech, Inc., to sell a series of “smart sponges” to address various environmental problems. The sponge can also be produced on a large scale to the tune of 3.35 tons per year, according to an email from Nandwana.

“This is a nanoscale solution to a gigaton problem,” Nandwana said.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @emmaeedmund

Related Stories:

— Northwestern Engineering synthetic biologists aim to create one-step diagnostic test for COVID-19

— Engineering, computer science majors top data on earnings after graduation