Reel Thoughts: On “Inventing Anna” and femalefrauding too close to the sun

Isabelle Sarraf/Daily Senior Staffer

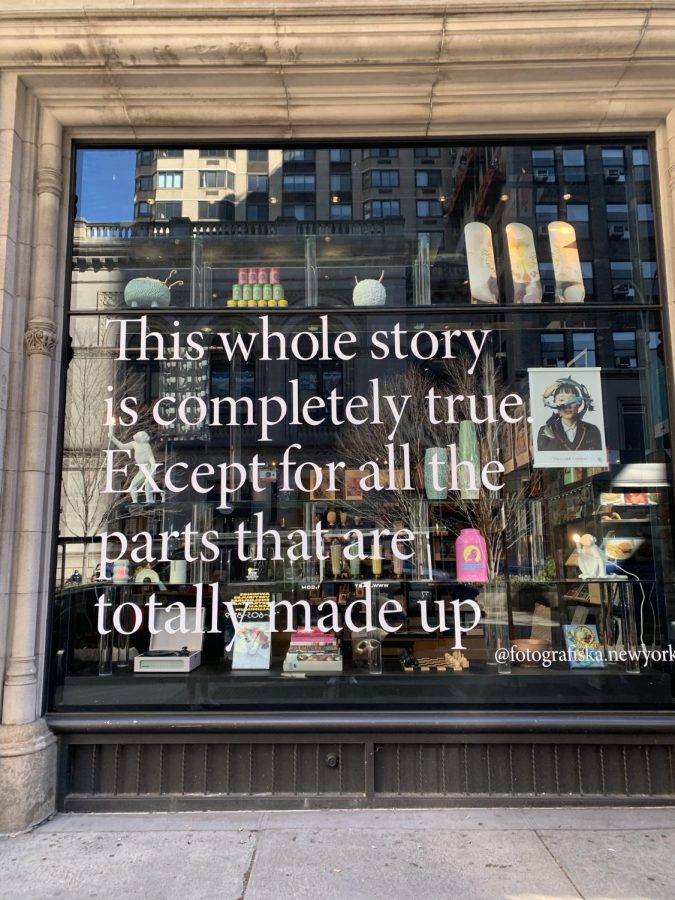

“This whole story is completely true. Except for all the parts that are totally made up” is written on the glass pane of the building that Anna tried to scam her way into owning.

February 27, 2022

This article contains spoilers.

As a fan of journalist Jessica Pressler’s salacious The Cut piece on Anna Sorokin — briefly known as Anna Delvey — I celebrated the long-awaited Netflix release of Shondaland-produced series “Inventing Anna.”

For those fascinated with female frauds like Delvey or Theranos’ Elizabeth Holmes, the show parses the complex journeys of women who build, maintain and destroy their personas in the pursuit of internal desires to be respected and seen. Set mostly in New York City, the series immerses viewers in the glamorization of its elite society, an environment where only the fast-paced, elegant and well-funded can thrive.

Two women sit at the center of the show: Anna Sorokin, a fake German heiress, and Vivian Kent, the Manhattan magazine journalist intent on penning Sorokin’s story. Arguably, the title “Inventing Anna” has two meanings: Sorokin’s invention of German heiress Anna Delvey and Kent’s permanantilization of Sorokin’s legacy through her journalistic pursuit.

There is something attractive about Delvey’s story: a mysterious socialite with an affinity for tipping waitstaff $100 bills, who dines at the chicest restaurants and rubs shoulders in a glamorous elite social scene, only to land in Rikers Island with multiple fraud charges.

And through the show’s muralistic title card, in which the faces of lives Anna has touched make up her own, it’s acknowledged early on that Anna is defined by her reputation — an unwieldy beast created in the wake of her outlandish yet distinctive personality.

Neff, a hotel concierge and friend of Anna’s, says in the first episode that everybody wants something: money, power, image, love. As she tells this to Kent, she unwittingly sets the stage for what the two main characters want. For Anna, it’s image. For Kent, it’s redemption.

An element of Kent’s backstory that comes into play is her battered journalistic credibility, which suffered the consequences of a major fact-checking oversight — namely public humiliation, the retraction of a Bloomberg job offer and banishment to the dead part of the office.

Because of this transgression, it’s clear one of Kent’s motives for pursuing Anna’s story is to save her own career. Otherwise, her professional life is in shambles and remains a source of anxiety for the expectant mother. It explains why Kent so vigorously pursued Anna’s story despite the innumerable obstacles in her way.

Kent sits through Anna’s fat-shaming insults, designer name-dropping and other attempts to establish a higher social status. She experiences firsthand how Anna “is not racist, but classist” and demands only the best in every situation, whether a private room at Rikers or designer clothes on the stand.

Anna’s cold and demanding attitude would normally be a turn-off, but in certain situations, she’s a charming conversationalist. If she’s not witty, she’s insistent and pressures the world to conform to her wants. Because her strength lies in emotional manipulation, the only roadblock that ends up stopping her is bureaucracy.

As the show emotionally spirals in tandem with Anna’s plans, viewers realize confidence can only take a person so far. Confidence can’t excuse poor treatment of friends, nor can it pay back thousands of dollars. An excess of confidence, as seen in the show, acts as a double-edged sword that drives a person to the top at the expense of those within their orbit.

Although the show attempts to bolster Anna’s case for victimhood, I became less inclined to root for her as the casualties of her storm began stacking up. We see the people around her go through emotional breakdowns, the personal lives of her allies suffer and walls of her scheme close in on her.

During her reporting process, Kent becomes caught in Anna’s schemes and gets too close to the story. When Kent travels to Germany seeking an explanation for why Anna is the way she is, she is intent on finding somebody else to blame. Surely, Anna must be a victim — of her family or of her circumstances, anyone but herself.

Viewers who wonder why Delvey’s allies are so loyal miss the point entirely. It’s not about Delvey, but their wants. For her lawyer, it’s to assert himself as a professional next to his well-established attorney wife. For Kent, it’s to save her career. For Neff, it’s to be next to the confidence she wishes she had.

From beginning to end, viewers watch as Delvey suffers the consequences of an excess of confidence, and ultimately becomes a warning for when our ambitions outpace our work.

Watching this show, and now gearing up for the release of a Hulu mini-series on Elizabeth Holmes, is like staring into a mirror and seeing an ambitious career woman’s worst fear: being labeled a fraud.

Does Delvey’s confidence excuse her actions? If anything, she’s a victim of her own ambition.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @WhoIsAlexPerry

Related Stories:

— Reel Thoughts: “The Book of Boba Fett” doesn’t do its titular character justice

— Reel Thoughts: “Dune” is definitely sand power, but does that matter for Hollywood?

— Reel Thoughts: “Spider-Man: No Way Home” is a messy but emotionally powerful Spidey flick