Northwestern researchers make a critical advancement in the treatment of Type 1 diabetes

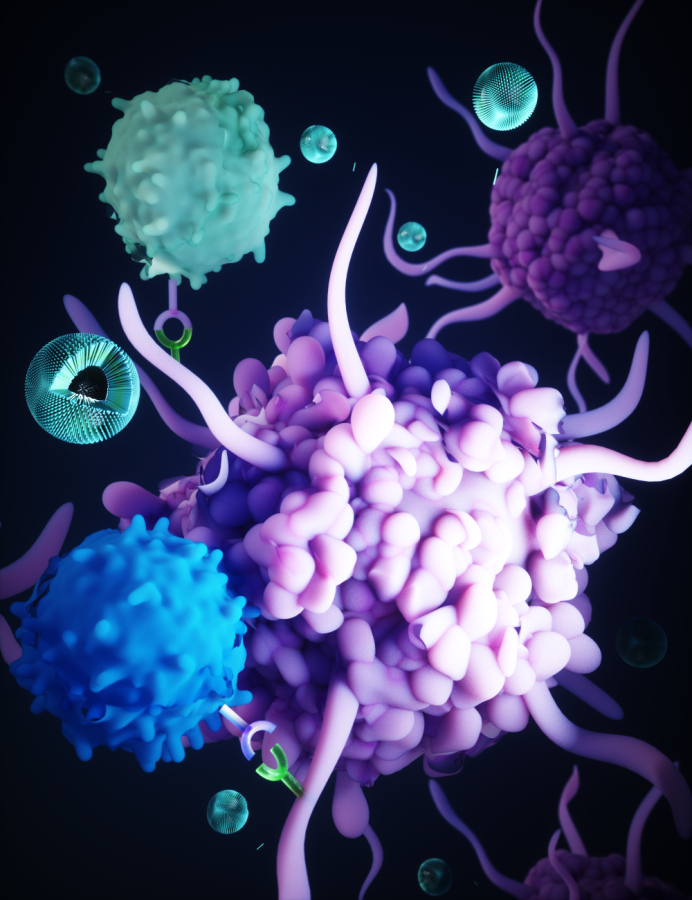

Photo courtesy of Northwestern Now

Northwestern researchers discovered a more accommodating treatment for Type 1 diabetes.

January 20, 2022

Researchers at Northwestern recently developed a new method that improves the treatment of Type 1 diabetes.

Using biomedical engineering and nanotechnology — the engineering of nanoscopic materials to conduct processes — researchers can make one-time insulin-producing cell injections into mice without provoking large-scale immune responses thereby invoking tolerance.

McCormick Prof. Guillermo Ameer said he joined McCormick Prof. Evan Scott roughly four years ago to pursue an immunobiology project undertaken by a graduate student. However, Scott said his work with Ameer began well before then.

“He was one of the faculty that helped mentor me,” Scott said. “We also do a lot of work together in diversity initiatives and regenerative medicine … we had been looking for a chance for our labs to work together and so this was perfect.”

Type 1 diabetic individuals are unable to produce insulin, a compound that helps reduce blood sugar concentrations and keep them at a healthy range. Although many Type 1 diabetics take insulin injections daily to account for this discrepancy, researchers found a way to regularly introduce insulin to the body internally so treatment requires only a one-time infusion.

This newfound treatment relies on transporting pancreatic islets, or regions of the pancreas that contain cells necessary for blood sugar breakdown, into the body. Recent biomedical engineering Ph.D. graduate Jacqueline Burke, who defended the project in her thesis, said her work centers around the study of pancreatic islets and their application to diabetic patients.

However, Burke said typical pancreatic islet transplants tend to have drastically negative impacts on patients. She added her motivation for making insulin-producing cell injections more comfortable stems from her personal relationship to the disease.

“I’m a Type 1 diabetic, so it’s particularly impactful for me,” she said. “The other issue is with this immunosuppressive therapy that is required … the side effects that are affecting patients are worse than living with Type 1 diabetes.”

Burke said her project, whose publication she co-authored with Scott and Ameer, subdues the immune system’s response to pancreatic islet transplants. By using nanotechnology, pancreatic islets can be inserted into the liver while avoiding a dramatic immune response, Scott said. In mice, this safe spot is the kidney, but for humans the liver is treated as such.

Scott added aspects of the process are similar to how modern vaccines work. When vaccines are inserted below the skin, immune cells can identify the disabled germ and alerts the rest of the immune systemso it can be easily targeted and destroyed in the future. However in the case of Type 1 diabetic immunotherapy, Scott said the goal is different.

“It’s like a vaccine,” Scott said. “Except in this case, the vaccine is teaching cells to not attack.”

This new development in delivering insulin-producing cells to the body without inducing retaliation from the immune system is a major development in immunobiology, according to Ameer. He said he and Scott’s research groups are the first to reveal the feasibility of this mechanism.

However, Scott said the development of a viable treatment for diabetic patients is still years down the road. The Scott and Ameer labs have only experimented with mice at this point, and while non-human primates are the next subjects to be tested, Scott said it will take many clinical trials and fundraising efforts until the Food and Drug Administration can approve a treatment

Ameer said he is proud of Burke for her hard work in outputting the project and is satisfied with the current publication of the project.

“I’m very satisfied that we have such high quality students that want to come up to Northwestern and join our teams … and do this type of high quality, high level work,” he said.

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify scientific terminology referenced and paraphrased throughout the story about the new development. The Daily regrets the errors.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @swarthout_iris

Related Stories:

— Psychology Prof. Onnie Rogers presents research on youth racial identity at IPR colloquium

— Psychology Prof. Renee Engeln researches body image and media with her Body and Media Lab

— Climate advocates, NU researchers promote clean energy to combat climate change