Bookends & Beginnings files class-action suit against Amazon, becoming face of new antitrust battle

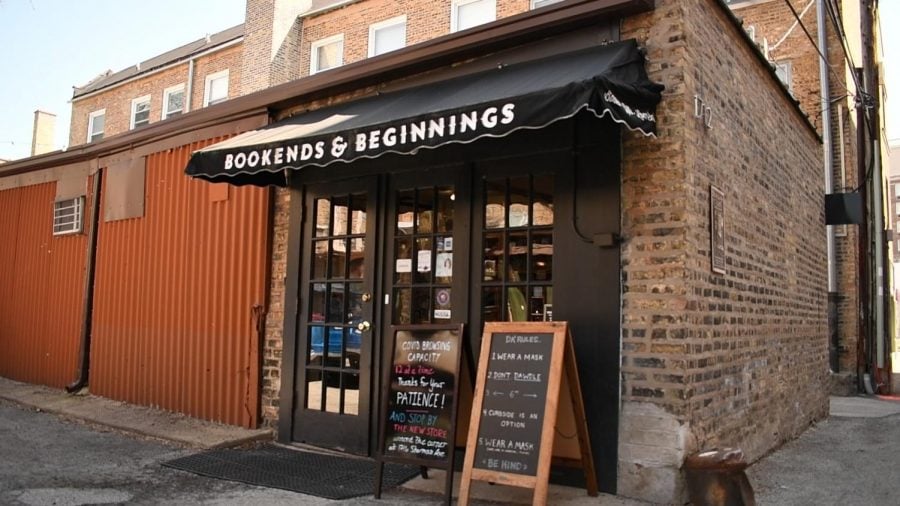

Anushuya Thapa/Daily Senior Staffer

Bookends and Beginnings’ alley entrance. The store, founded in 2014, is the lead plaintiff in a new antitrust lawsuit.

April 8, 2021

When Nina Barrett (Medill ‘87) expanded Bookends & Beginnings earlier this year, she hoped the bookstore’s new window on Sherman Avenue would increase its visibility. By late March, the window was serving a higher purpose: displaying copies of a bright orange booklet, titled “How to Resist Amazon and Why.”

Barrett — and Bookends — are well acquainted with the zine’s message.

The independent Evanston bookstore is the initial plaintiff in a class action lawsuit filed on March 25, which alleges Amazon and the nation’s five leading trade book publishers have restrained competition, fixed prices and created a monopoly in the print trade bookselling industry.

“We’re not supposed to have bullies on the playing field that prevent entrepreneurs and small businesses like mine from existing,” Barrett said. “So when (the law firms) invited me to become essentially the face of the case, I was totally ready to do that.”

Two firms with antitrust experience, Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP and Chicago’s Sperling & Slater, P.C. — which recruited Bookends — filed the complaint in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Amazon’s co-defendants in the case, Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster, combine for an estimated 80 percent of the trade book publishing market. Trade books are those written for a general audience and not for academia or reference, and often comprise most of bookstores’ selections.

Amazon, which did not respond to The Daily’s request for comment, accounts for over half of the country’s print book sales, and more than 90 percent of online print book sales. Barrett, who founded her store in 2014, is hoping the suit will help change Amazon’s business practices and award financial damages to independent bookstores — recompense for the way they’ve been choked out of the bookselling market.

The complaint argues that preferential “most favored nation” clauses between Amazon and the publishers combine with Amazon’s dominance to hurt booksellers and consumers. These clauses generally mandate that a business be treated no worse than any competitor. In 2020, a U.S. House Judiciary Committee investigation accused Amazon of forcing the clauses upon book publishers by threatening financial penalties.

Because of the clauses, bookstores are unable to buy books from publishers at cheaper rates than Amazon or release books before the internet giant does, essentially leaving no room to compete, the complaint alleges.

The bookstore lodges its allegations as proof the defendants have violated the Sherman Act, which outlines U.S. monopoly and competition law.

Because the complaint was filed as a class-action lawsuit, other retail booksellers will be able to join the case if it continues, be represented by the Evanston bookstore’s arguments and benefit from a possible positive ruling.

“People are talking about it as if it’s a David versus Goliath. But I am not the only David here,” Barrett said. “Every single independent bookstore in the country is fighting the same struggle that I’m fighting, and is being invited to join the suit.”

Bookends, small businesses, and the pandemic

Independent bookstores have struggled during the pandemic, and Barrett said in the beginning, the outlook was especially frightening.

The lockdown, she said, proved to be a major obstacle. She launched a GoFundMe for the store — which raised almost $50,000 — and Bookends attempted to reach more customers online. The store also received a Paycheck Protection Program loan.

Then, Barnes & Noble left downtown Evanston, which sent more customers to Bookends and encouraged Barrett to expand her storefront.

Many other bookstores haven’t made it. Allison Hill, the chief executive officer of the American Booksellers Association, told The Daily 72 of the organization’s 1,800 member bookstores closed in 2020. She said while the pandemic hit hard, Amazon had already been causing trouble — she described the company as a “preexisting condition.”

“Amazon has been ‘boxing out’ local bookstores and other small businesses all across the country, resulting in the losses of local jobs; local sales tax revenue; and a sense of neighborhood personality, community, and tradition,” Hill said in an email.

That sense of community is vital to Barrett, who sees her business as a “third place” for people — somewhere outside the workplace and home where they can find uplifting interaction. She said the experience at Bookends is antithetical to Amazon’s quick, personless platform.

She said she has seen the effects of Amazon’s dominance for years, and not known how to stop it.

“Do I feel in any way bad about poking them? No. Do I feel silly, because I’m so little, and they’re so big? No,” Barrett said. “It has to start with somebody speaking up.”

The wider fight

The fight against bookselling monopoly power didn’t start in Evanston, even though Bookends has become its newest face.

Hagens Berman, one of the law firms representing Bookends, sued Amazon and the publishers earlier in 2021 for ebook price-fixing. The plaintiffs in that case were consumers rather than stores.

Managing Partner Steve Berman told The Daily the firm has received “considerable, positive interest” from other bookstores around the country about the newest suit.

In tandem with the U.S. Department of Justice, the firm also sued Apple and the publishing companies in the early 2010s for ebook price-fixing. The antitrust case eventually yielded around half a billion dollars in payouts to ebook readers.

The government and academic worlds are grappling with what antitrust cases look like in the age of big tech. President Joe Biden intends to work with Lina Khan, whose 2017 paper “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox” launched a stiff critique of the company’s business practices.

Khan’s key point was that American antitrust policy is too focused on prices for consumers, and not enough on the relationships between businesses. The Bookends suit is in what may become a popular vein of antitrust litigation, accusing Amazon and the publishers of stifling competition.

“My beef is with having this ginormous, faceless website, which is buying books on different terms from mine for different reasons — not because they care about books,” Barrett said. “Just because, well, it helps them become an even more ginormous business.”

Anushuya Thapa contributed reporting.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @stephencouncil

Related Stories: