Civic leaders, organizers discuss impact of EPD limiting practice of arresting minors

October 1, 2020

Iain Bady was arrested at 12 years old.

After he rode on the back pegs of a bicycle a friend drove into traffic at a stoplight, Bady was arrested and brought to the Evanston police station in July 2017. He was cited with violating an Evanston ordinance that prohibits the operation of a bicycle in any way that obstructs traffic flow. Now 15 years old, Bady described the impact of the realization he had been racially profiled by Evanston Police Department as he spoke during an August 31 city Q&A session.

During the conversation, Evanston Police Chief Demitrous Cook apologized directly to Bady for EPD’s conduct during the incident.

After Bady shared the experience of his unfounded 2017 arrest and the challenges it brought him and his family, Cook asserted that the higher rate of arrest for Black youth in Evanston “had to stop,” adding that he hoped “not to have any juveniles in the station.”

“When you look at interaction with youth as young as Iain when he was 12, and the interaction with youth that may be younger than him, you’ve got to look at an aspect of trauma that has never been addressed in law enforcement,” Cook said. “Historically, we’ve had a lot of youth destroyed, their reputation and criminal history, by arresting them at such a young age.”

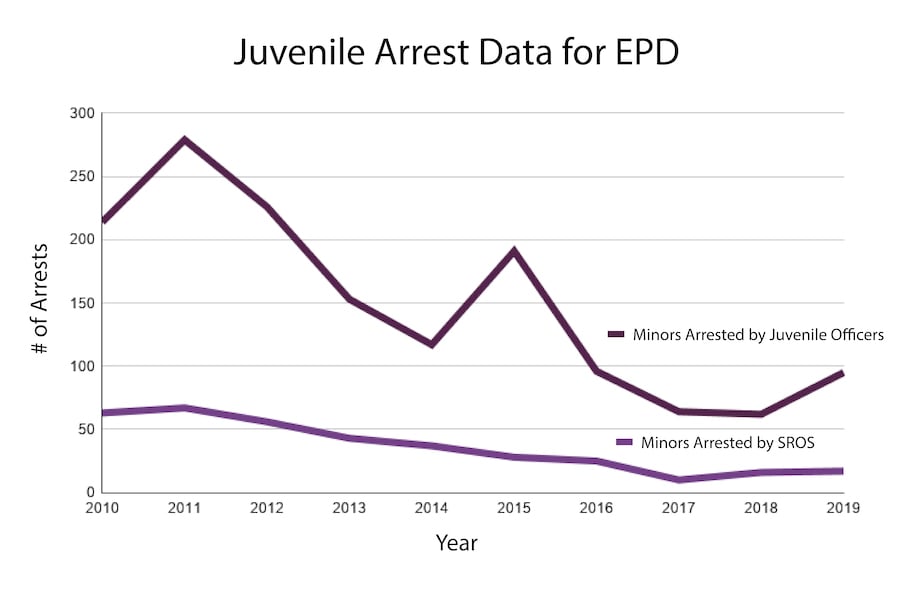

For some local restorative justice leaders, the chief’s statement was a promising indicator of positive change — especially coming on the heels of last year’s spike in juvenile arrests by EPD, breaking a trend of steady decline since 2015.

Betsy Clarke, the president of the Juvenile Justice Initiative, said she was encouraged when she heard the chief’s response, noting she believes it would be a good first step to reversing that spike — and the trauma it could inflict on Evanston youth — as well as build trust in neighborhoods that have been concerned about over-policing.

“The police should find ways of dealing with conflict involving children that don’t involve bringing them to the police station,” Clarke said. “There might be a few exceptions, but in every case possible, that should be the default.”

The impact of an arrest

Patrick Keenan-Devlin, the executive director of the Moran Center for Youth Advocacy, has spent the bulk of his career representing minors who have been arrested and petitioned to court in the Circuit Court of Cook County for prosecution. He’s witnessed both the arrests and processing of minors at the police station, and described it as “an incredibly traumatic affair.”

“There is nothing adult about a 17-year-old sitting in a jail,” Keenan-Devlin said. “I don’t know if I’ve ever sat in a jail cell with a child who has not wept openly out of fear, confusion.”

According to EPD’s annual reports, the Juvenile Bureau, which handles investigations involving juvenile victims and/or alleged offenders, arrested 112 minors in 2019, 17 of which were arrested by School Resource Officers (SRO’s).

This number was a jump from the previous two years, which saw an average of 76 juvenile arrests by the bureau — the lowest in a decade.

“These are not statistics — they’re kids,” Keenan-Devlin said.

For many local advocates, this spike was alarming, especially considering the efforts of the Evanston City Council and the Alternative to Arrests committees over the past two years to create an “off-ramp” from the juvenile court system available to EPD.

When EPD is faced with arresting a minor, Keenan-Devlin explained, the department can issue C-tickets “where possible and appropriate” for myriad non-violent ordinance offenses and misdemeanors, citing youth for low-level offenses instead of arrest.

They would then be referred to the juvenile administrative hearing process — a forum that recently relaunched in September after being on pause due to COVID-19 — where they would work with a social worker to develop an individualized repair of harm agreement.

According to data he received as a member of the Alternative to Arrests committee, Keenan-Devlin said EPD has referred 19 individuals to the juvenile administrative hearing process since the forum launched last July.

While low, he said he sees these referrals as a good initial indicator of progress towards harm mitigation. The referrals mean EPD is beginning to reroute minors from juvenile arrest to a community-based process that doesn’t involve the very traumatic elements of an arrest and won’t result in a permanent record, he said.

“I have to infer from Cook’s statement that his hope is that we can build a community where arrest is the exception, and not the rule,” Keenan-Devlin said.

A reactive approach versus a proactive solution

However, some community members don’t have as much faith in Cook’s promise. Mollie Hartenstein, an organizer with Evanston Fight for Black Lives and an ETHS alumna, said she has seen Cook make broad statements appealing to community requests, only to have them walked back at a later period by himself or other members of EPD and city leadership.

Sarah Bogan, a fellow EFBL organizer and ETHS alumna, highlighted a flaw she sees in Cook’s assertion: alternatives to arrest don’t seem feasible if significant portions of EPD’s budget aren’t reallocated to fund those programs. If those alternatives aren’t readily available in all cases, she said, only so much harm can be mitigated.

Bogan and Hartenstein said preventative measures should incorporate plans to end conditions that foster criminalization. Some of the EPD officers she has spoken to do recognize the need for mentorship programs, reparations, and “more for the Black and Brown communities in Evanston,” Bogan said.

However, she added that they don’t necessarily agree that having disproportionately high numbers of police in wards where significant portions of the city’s Black and Brown populations live is a problem, or that it may not be their job to intervene in every case.

“If we want to stop [youth] arrests, I don’t think that police should be the ones necessarily handling these situations,” Bogan said. “There should be a different hotline for youth when something’s happening, so there can be a proactive intervention that’s coupled with [counseling and social services]… We’re trying to stop this at the root, not just react. You can’t take an action such as ‘we’re going to stop arrests’ without having a solution to the problem.”

Email: daisyconant2022@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @daisy_conant

Related stories:

— EPD phases out Stop and Frisk policy, but advocates say pat down data shows racial disparity

— Evanston police undergoing internal investigation following arrest of black 12-year-old cyclist