NU researchers develop wearable device that helps monitor COVID-19 symptoms

Courtesy Northwestern University

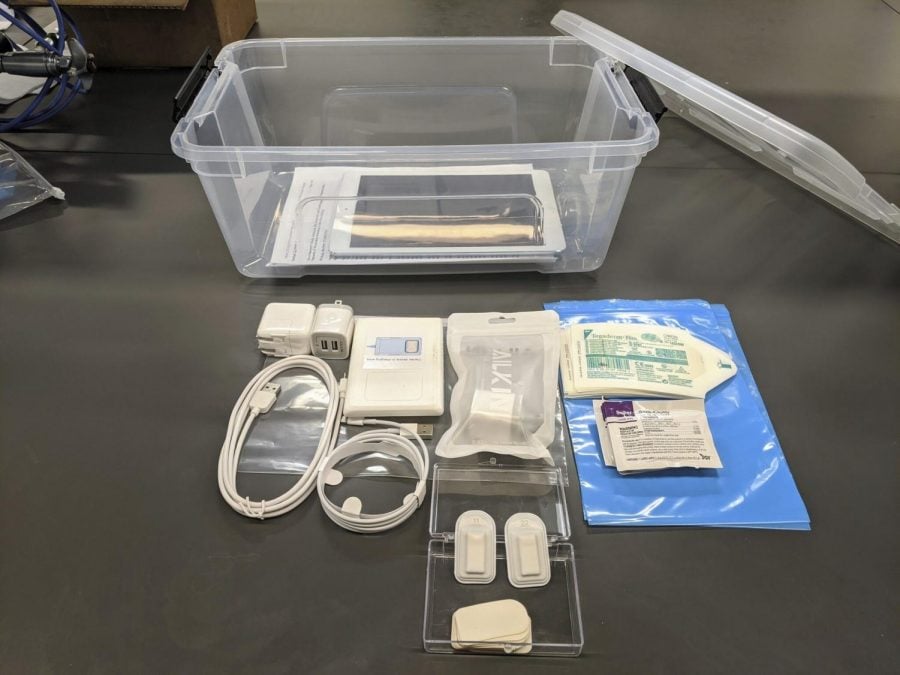

A team of Northwestern researchers, in collaboration with Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, developed a wearable device that can monitor COVID-19 symptoms. The device was originally designed for stroke patients to help improve speech and swallowing rehabilitation protocols.

July 14, 2020

A team of Northwestern researchers recently developed a wearable device that helps detect early symptoms associated with COVID-19 and monitor these symptoms as the illness progresses. The wireless device is designed to mount like a Band-Aid onto the suprasternal notch, the spot on the base of the neck right above the point where the collarbones meet.

The device functions like a “wireless digital stethoscope” in that it works by measuring vibrations on the surface of the skin, according to McCormick Prof. John Rogers, who led the Northwestern team. It records data on respiratory and coughing patterns, heartbeat and temperature into a memory module built into the device. This data is then compared with pre-existing data collected from people with COVID-19, people who have recovered from it, people who are sick but don’t have COVID-19 and healthy people. As a result, this algorithm can help monitor symptoms for a wide range of people.

The Rogers lab collaborated with researchers at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab to create the device. Feinberg Prof. Arun Jayaraman, a research assistant scientist at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, led the algorithm development.

The two groups originally developed a similar device meant to help refine speech and swallowing rehabilitation protocols in stroke patients. But when the pandemic happened, the researchers developed this device in response to inbound requests from physicians.

“We were worried about creating our own mini pandemic [at the hospital],” Jayaraman said. “So what we wanted is a continuous monitoring system so we can keep an eye on our clinicians and patients who are not positive, but if somebody became positive too quickly, [we can] isolate them and then get them tested with a nasal swab.”

As a result, the groups were able to modify their stroke rehabilitation device to address COVID-19 symptoms instead and accommodate the requests from the clinical community.

Hyoyoung Jeong, a postdoctoral fellow in the Rogers lab, said he is happy with the device because of its potential and the rare opportunity for it to get tested on actual patients.

“This device has so much potential to measure multiple biometrics and it’s a really great chance for me as well because our group has a very good relationship with (Northwestern Memorial Hospital),” Jeong said. “So we can really apply this device to the real patients, so it’s a very rare chance actually.”

He added that in the future, he hopes the device will be able to measure other biometrics as well, such as brain signals.

Rogers said the team received funding from the National Science Foundation to add a sensor to measure blood oxygenation to this device. Blood oxygenation levels have been found to be very important to monitor in the context of COVID-19, he said, due to the disease’s respiratory nature. He added digital technologies like this may be able to complement molecular-scale testing since molecular testing is limited, while with a digital sensor, people can be monitored continuously without consuming extra resources.

“With molecular testing, you’re consuming material every time that you do a test,” Rogers said. “And that creates some level of constraint on how frequently you can test and how many people you can test. I mean, there are just limits associated with producing the swabs, producing the reagents, handling the samples, all this kind of thing.”

As a result, the limited COVID-19 testing resources can be allocated to those who really need them rather than wasted on people who may be a “secondary priority.”

Email: vivianxia2023@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @vivianxia7