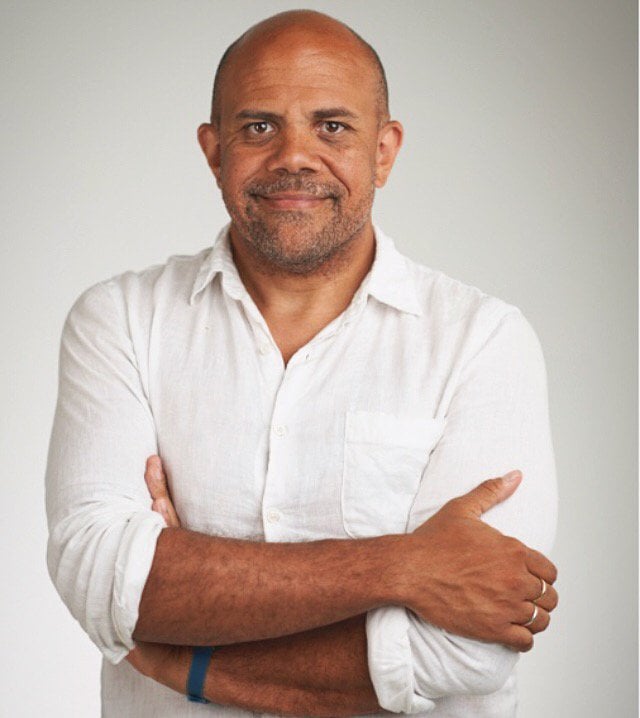

Dr. Steven Thrasher talks protests, coronavirus and policing

Dr. Steven Thrasher is the inaugural Daniel H. Renberg Chair of social justice in reporting. His new class provides a space for students to think and learn about how viruses intersect with issues such as race, sexuality, disability, economics and the news media.

June 3, 2020

Dr. Steven Thrasher is the Daniel H. Renberg Chair of social justice in reporting at the Medill School of Journalism as well as a faculty member at the Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing. On Tuesday, Campus Editor James Pollard interviewed Thrasher about the current protests spurred by the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd, the coronavirus pandemic that has disproportionately affected Black Americans, his reporting on the Black Lives Matter Movement and his recent article in Slate. This interview has been edited for clarity.

The Daily: How does what you witnessed in Ferguson six years ago compare to what’s happening right now?

Thrasher: This was the first time I think the general public — and certainly was the first time I personally — understood that this military equipment that was being used in Iraq and Afghanistan was starting to be used in Ferguson. And I remember my first day there, because I used to be an education reporter years ago just before that, I wanted to understand what Ferguson was like through the eyes of kids. It was really interesting to hear from them what it was like to see these tanks and the ways they were thinking this was an invading army. And some of them could only reference it, sort of, through thinking of Call of Duty.

The Daily: And do you think this time around the police are militarizing and responding with violence in an even greater way than they did in 2014 and in the years since? Is there something different about their response this time around?

Thrasher: Yeah, so in a way Ferguson is everywhere. I mean, that was a phrase that you would hear at the time as well, “Ferguson is everywhere,” but it certainly feels so fast and so coordinated. Ferguson was certainly the most extreme response at that time. And then we started seeing similar things in Baltimore and other places. This time, just in a matter of days you’re seeing (it in) multiple cities. I have a cousin who is a police officer in a very small community in the Midwest and they’re all in the riot gear in this town of 40,000 people. So I feel like what happened to Ferguson, we’re seeing it just very broad and very fast. The police techniques look very similar. I think the reactions are different than what I was seeing in 2014.

With Ferguson, there wasn’t even an attempt for a long time for national leaders to maybe single out Darren Wilson, the police officer — and certainly not from the local local law enforcement. So it was months later that he wasn’t indicted. (In Minneapolis) the mayor fired (the four police officers involved in the death of George Floyd) almost immediately, which was shocking to me. And that’s very different from New York City with (Mayor) Bill de Blasio, and Daniel Pantaleo who choked Eric Garner, who was also, “I can’t breathe” — his last words. And so that was very fast. And then there was lots of condemnation, lots of people wanting to say “these were bad apples.”

But I find the two most significant things I saw early on (this time) were when the University of Minnesota said they were going to stop using the police in joint exercises. Now they, like Northwestern University, have their own police force. But they said they weren’t going to engage with the Minneapolis Police Department anymore. And that’s a very different thing to say than the bad apples questions — that’s saying there’s something wrong with this institution. And then, I think it’s tonight, the Minneapolis Public Schools are considering a resolution to get rid of their contract entirely and not have the police come in. And that’s super interesting. And that’s built not just on this event itself, but there are organizers — primarily led by black youth and students themselves — who have been asking for this for years. And now they’re gonna take it seriously.

The Daily: These protests and the police violence are coming amid this pandemic that’s disproportionately killing black people, where prisons have become hotspots for the spread of this virus. With the unemployment rate hitting its lowest since the Great Depression, more people are also questioning this country’s economic structure. How do these political frustrations that have been exacerbated by coronavirus relate to these nationwide protests against police brutality?

Thrasher: I think they’re very much connected. And as I think back on the protests that I’ve covered over the past 10, 12 years, protesters have organized around a number of different things — largely which have not been met. So Occupy Wall Street was really a reaction to the financial crash of 2008. And there are all these things that (after) what happened in 2008, people have never kind of recovered, or they just barely started to recover and now all those gains have been blown. So people have never really been made whole from what they’re protesting on Occupy Wall Street, certainly around systemic racism, environmental things, Standing Rock, things like this. There hasn’t been real justice around them. And then along comes this pandemic that not only, as you were saying, disproportionately is affecting black people, poor people, immigrants — it’s not only affecting them. It’s most affecting them. The cracks, they’re getting wider and wider and more people are falling in. And people have all this time on their hands. I think they’re spiritually hungry to be connected to other people since everyone’s been so isolated.

Prior to kind of being a full-time journalist myself, I worked for a year for the NPR StoryCorps project. I worked for a year for them where we were interviewing people who’d been involved in the civil rights movement in the mid-20th century. And I’ve always remembered one person saying what doesn’t get covered in history is that it was fun. You see the drama, you see the dogs and the scariness of course. But it was also really fun to be singing, to be chanting. And that’s something I’ve thought about a lot — that being in protest it can be very scary. Of course it’s extremely terrifying when it gets to the end. But there is a real joy in it.

And there’s a real feeling of connection and community. There’s a joy, I think, that people feel in standing up for each other. It is significant that this killing happened the week when we had a hundred thousand deaths in this country. And there’s been no national mourning. There’s no national day of remembrance. As far as I know, there’s been no national TV broadcasts to read the names. And it’s certainly not coming from this president.

My late sister was a therapist. She told me something I thought of a lot after she passed away — how unexpressed grief turns into rage. And if you’re not allowed to feel grief and to cry or to mourn, then it just becomes anger. It becomes this very, very pent up anger. And that can act out in all kinds of ways. It can act out negatively inside one’s body in terms of hypertension and heart disease and things of that nature. And then it can also get expressed in really dramatic ways. I think that’s part of what we’re seeing now.

The Daily: And in your most recent piece for Slate — it was called “Proportionate Response: when destroying a police precinct is a reasonable reaction” — you wrote that for about a decade you’ve been reporting on “the violence of policing.” And you said you phrased it that way specifically because “policing is always violent.” Could explain how you’re trying to reframe the conversation about what types of violence are considered in moments like this? I think there’s a tendency in American media and from politicians to focus on material violence. So I’m wondering if you could explain that line, that “policing is always violent?”

Thrasher: I started thinking that policing could always be violent (on) the day that I reported on a protest in New York City. And it was about Eric Garner, who also said “I can’t breathe.” He said it 11 times before he died. And I’d heard that it was going to be led by his daughter, Erica Garner, who I’ll tell you more about in a minute, who’s now also dead. And I’d heard there was going to be a counter protest of people. And so I went and the counter protest was — people told me — off-duty cops. I couldn’t tell whether they were NYPD or not or from out of town. But they had shirts on that said not “I can’t breathe,” but “I can breathe.” And they were there to taunt the daughter of this person with her father’s dying words. And so I started really thinking about experiences I’ve seen other people have with the police and I wrote that night a question like, “Is the threat of violence a form of violence itself?”

I’d seen my father get harassed by police. My great grandfather was chased out of his home by the (Ku Klux) Klan. And I thought about the one incident I had with a police officer that left me the most rattled. I had been on a run near Central Park on a day where the streets were open many, many years ago. I didn’t have a watch. This was almost pre-cell phone, that’s how old I am. And I saw a couple cops chatting amiably and I asked one of them if they knew the time. And he put his hand on his gun and started to draw it out of his holster and saw the terror on my face and then just said, “Hahaha I’m just joking. It’s, you know, 12:42.” And so that is a form of violence. It made me think the threat of violence that cops are always holding over people is a form of violence itself.

The threat of having to make people do something with a gun is itself a form of violence. If a man and a woman were a couple and the man wants the woman to do something and he holds a gun at her, we would call that domestic violence. So when the state can only compel people to do things through pointing a gun at them, I think that’s a form of violence.

One of the things we’re seeing people so amped up about right now is people are terrified that they’re not be able to buy food or pay rent. And so if money is going to go to the police, or sheriff it might be in some places, to violently evict somebody, what if we just put money in their pockets in the first place so that they weren’t going to have to be evicted?

Editor’s note: The Minneapolis public school board voted unanimously to terminate its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department hours after this interview took place.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @pamesjollard