The budget surplus, explained

Daily file photo by Colin Boyle

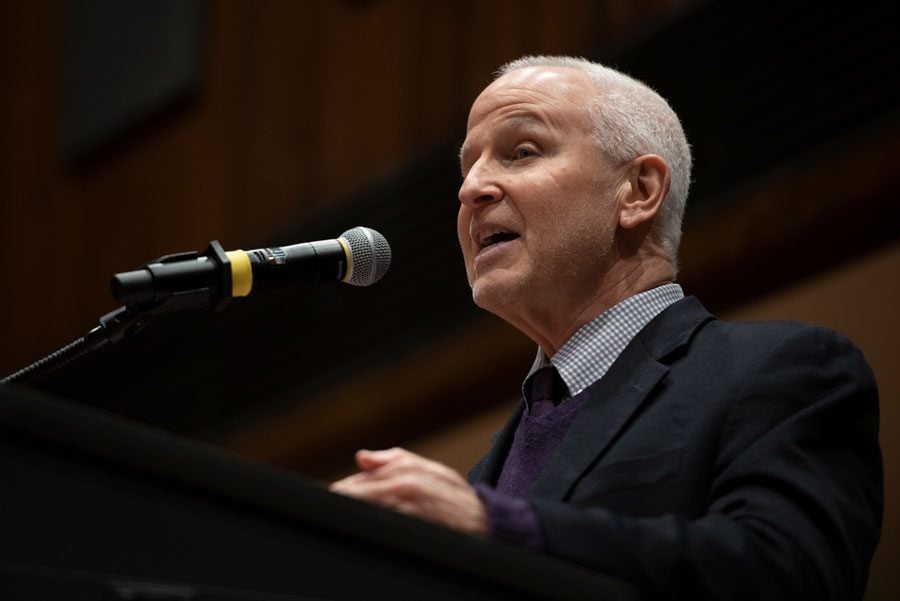

Northwestern President Morton Schapiro. The University finished with a surplus of over $60 million.

January 21, 2020

In the two years since Provost Jonathan Holloway disclosed the University’s budget deficit to Faculty Senate, administrators made cuts to academic departments’ budgets, laid off dozens of staff members and even cut down on some holiday tree lights and students’ beloved ice rink.

With a budget surplus estimated to be $66.5 million in a January 9 email to the Northwestern community by University President Morton Schapiro and $68.7 million in the 2019 Financial Report, administrators now have a “small but important” fund with which to make needed investments while maintaining some of the controls that helped balance the budget, Schapiro wrote.

“A challenge we always face is to balance short-term interests with the commitment our University has made to serve future generations as capably as this one,” Schapiro wrote in the email. “Discipline remains essential, as our revenue streams and endowment are subject to shifts in the economy. Thus, we have asked campus leaders to continue with prudence in their Fiscal Year 2021 resource planning.”

Vice president for business and finance Craig Johnson told The Daily earlier this month that his office will be using the surplus money to “layer (spending) back in” to a few areas of need that did not receive sufficient investment during the two-year budget deficit. One such area is Counseling and Psychological Services. Johnson said the University will be “deploying more resources” to add positions to CAPS, including a sports psychologist, with more details to be announced soon.

Construction on building projects that had been put on hold — such as the Donald P. Jacobs Center, the James Allen Center and the top floors of Mudd Library — will resume. The surplus will also be put toward funding the Faculty Pathways Initiative and implementing recommendations from the Undergraduate Student Lifecycle Committee toward improving the experience of first-generation, low-income students on campus, including dedicating a community space.

Johnson said spending on information technology and the faculty and staff compensation pool were among the first cuts in 2018. With new cash on hand, the University is planning to fund new IT infrastructure to defend against cyber-attacks and provide for maintenance updates.

The July 2018 layoffs of 80 staff members was arguably the toughest and least expected consequence of the deficit. While no faculty members were laid off, Johnson said the faculty salary increase pool was a “modest 2 percent” with a salary freeze for administrators, deans, managers and other high-earners, and a 0 percent merit raise pool to ensure there would be no layoffs. The rate of inflation for 2019 was 2.3 percent.

The University paid out about $19 million more in salaries, wages and benefits in the 2019 fiscal year than 2018, which represents the modest 2 percent salary increase pool and a 1 percent decrease in staff salary spending due to the layoffs. Johnson said in the years before he arrived in 2018, that ‘salaries’ line item was regularly increasing around 8 percent.

“We were finally able to bend that cost curve,” Johnson said. “But, it took a lot of hurt.”

For the schools that rely on the University for funding, which includes all of the undergraduate schools, budget administrators will “get the full amount possible” for salary increases and merit raises, he said. The new funds will be distributed equally across departments.

The deficit was also curbed by the controls placed on expenses, including the 5 to 10 percent cuts to operating budgets across the University, including all academic units, student groups funded through the University or departments and administrative units. Those budgets won’t return to their pre-cut levels, Johnson said.

While the cuts contributed to ending the deficit, the surplus was created through greater earnings in a number of revenue streams. Between the 2018 and 2019 fiscal years, the University earned $30 million more in tuition, $20 million more in unrestricted private gifts and $48 million more in payouts from grants and contracts from federal and other sponsors this year. Some of that revenue was nullified by the $19 million more the University paid in salaries, wages and benefits, a modest increase compared to other years, the $18 million more it spent in interest on its debts, the $15 million more in depreciation expenses and the $36 million less it took in investment returns designated for the operating budget.

Ultimately, the differences resulted in the $60-plus million surplus.

In order to ensure the University stays in the black, Johnson said administrators have centralized the budgeting process and imposed controls on units’ budgets so that they function more like checking accounts where there are mechanisms to prevent overspending. All requests for new funding are handled through a centralized system, so relevant administrators are all aware of spending and funds are not coming from different sources with different amounts of information.

“There’s infrastructure in place,” Johnson said, “to ensure commitments don’t get made without figuring out how we’re going to pay for it.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @birenbomb