Interdisciplinary research team awarded $10 million NIH grant to develop device to treat opioid overdose

October 29, 2019

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from Northwestern and Washington University in St. Louis won a $10 million grant to develop a device that can identify a life-threatening level of opioids in the bloodstream and automatically administer a dose of naloxone, an antidote, to prevent death from overdose.

The team will receive the grant from the National Institute of Health’s Helping to End Addiction Long-term Initiative over the course of five years.

Over 42,000 deaths in the U.S. were attributed to opioid overdose in 2016. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared a public health emergency regarding the opioid crisis. The prevalent way to treat an opioid overdose currently is to deliver naloxone.

McCormick Prof. John Rogers, one of the principal investigators on the project, said because the device is implanted into a human body, there were certain factors the engineering team had to consider while designing the device.

“Nobody’s ever tried anything like this before,” Rogers said. “So we have to worry about long-term stability, we have to worry about immune response to the device, we have to worry about reliability and the operation.”

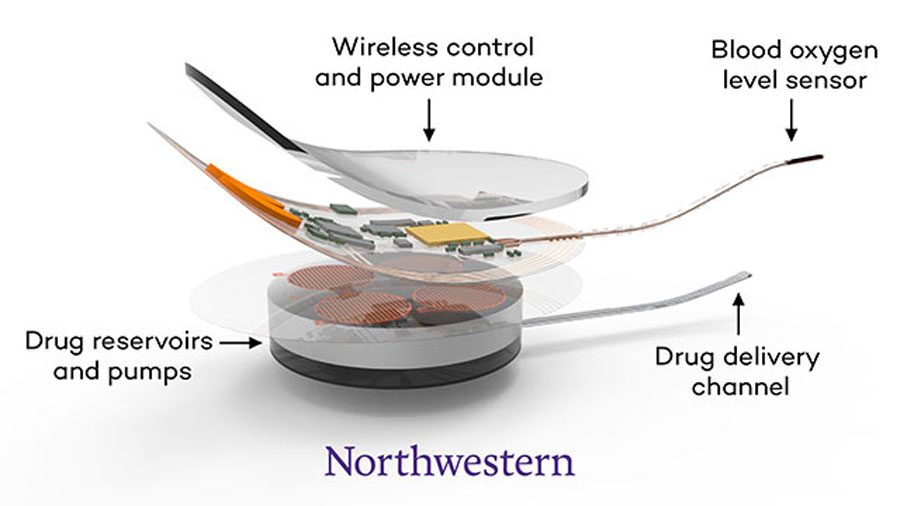

The device, which is about the size of a small USB drive, monitors the oxygen level in the blood, which decreases when someone overdoses on opioids. If it senses a problem, the device delivers a dose of naloxone without outside intervention.

The moments following an overdose are critical, as a dose of naloxone must be administered by a trained professional to reverse the effects. However, if there aren’t people around, then there is a chance that no one will come to help the person who overdosed or the naloxone will be administered too late.

The device is currently in the trial phase and will start rat testing in January, Rogers said.

Abraham Vazquez-Guardado, one of the members of the research team at Northwestern, said there were different challenges the team ran into when designing the device. He noted the challenge of maintaining a connection between the device and an “external link” because of a power issue.

Vazquez-Guardado said it was interesting to work on something that highlighted the intersections between biology and engineering.

“We are correcting a particular pathology in the system,” Vazquez-Guardado said. “It will have direct implications or benefits for the (patients), which is always something people who are designing try to look for.”

Robert Gereau, a professor at the Washington University School of Medicine and the other principal investigator on the project, said in an email that some raised concerns about whether the device would promote “risky behavior” in opioid addicts because they had a method to overcome overdose. However, Gereau and Rogers both dismissed this concern.

Gereau said the device was intended for people coming out of inpatient rehabilitation, who although striving to remain sober, still have a chance of relapse.

Opioid users develop a tolerance to the drug while they are regularly using. However, if people use after coming out of rehab, where they were sober for an extended period of time, they have a higher chance of overdosing because their tolerance has decreased. Gereau said these are the overdoses the device is meant to prevent.

However, Gereau emphasized that the device had a separate purpose from methods of prevention for opioid addiction.

“This is not a device to treat opioid addiction,” Gereau said. “It is intended to prevent death from accidental overdose. Treating opioid use disorder is a related but separate issue, requiring an integrated, multi-pronged approach. Our device is intended to reduce the number of deaths from accidental overdose, which often happens during the course of treatment for opioid use disorder.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @neyachalam