Northwestern sets its eyes on a new decade

Daily file photo by Colin Boyle

The Arch, one of Northwestern’s most recognizable symbols. Provost Jonathan Holloway said the school will have to confront demographic changes in the decade to come.

April 29, 2019

When University president Morton Schapiro was appointed in 2008, he took the reins of a school about to embark on a new decade. Northwestern looked different then — it had a 26 percent acceptance rate, tuition was $38,000 per year and Bobb-McCulloch Hall was, well, still Bobb-McCulloch, which Schapiro acknowledges.

Now in his tenth year, with the school again on the cusp of a new decade, Schapiro said the changes to both the University and academia at large are noticeable.

In particular, he noted Northwestern’s climb in the ranks and establishment as a research powerhouse. Crediting his predecessor Henry Bienen, Schapiro said Northwestern went from being ranked 41st for National Institute of Health funding to 21st by the time he took over in 2008. During his tenure, NU has reached 15th place. Over the past decade, his priority for Northwestern has been to continue to raise the school’s research profile while re-emphasizing the undergraduate experience.

“It was time to refocus on undergrads, to improve the quality of the dorms, improve the quality of the health center, improve the quality of career services, and just put more money into the undergraduate experience,” Schapiro said.

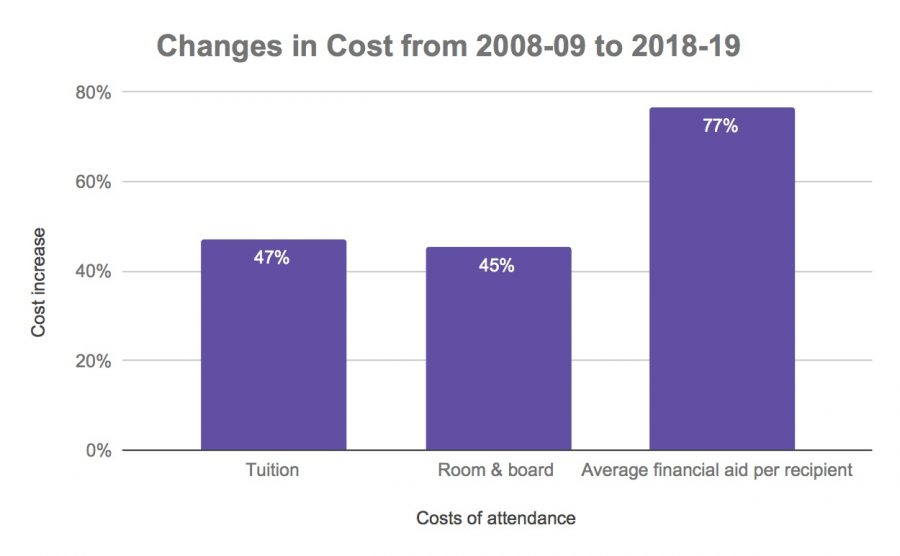

Though Schapiro said undergraduate tuition now makes up only 8 percent of Northwestern’s budget compared to 12 percent when he arrived — and the rate keeps decreasing — devoting time, energy and resources to undergraduate is a necessity considering how selective the school has become, and how talented the current student body is.

Going into the next decade, Schapiro said Northwestern will continue to prioritize both research and the undergraduate experience.

“I believe we can continue to improve the teaching and the living experience in a more inclusive manner than we’ve had and you could still be a major research machine,” Schapiro said. “So, that’s what I’ve tried to do. And as long as I’m here, I’m gonna try to do both of those things.”

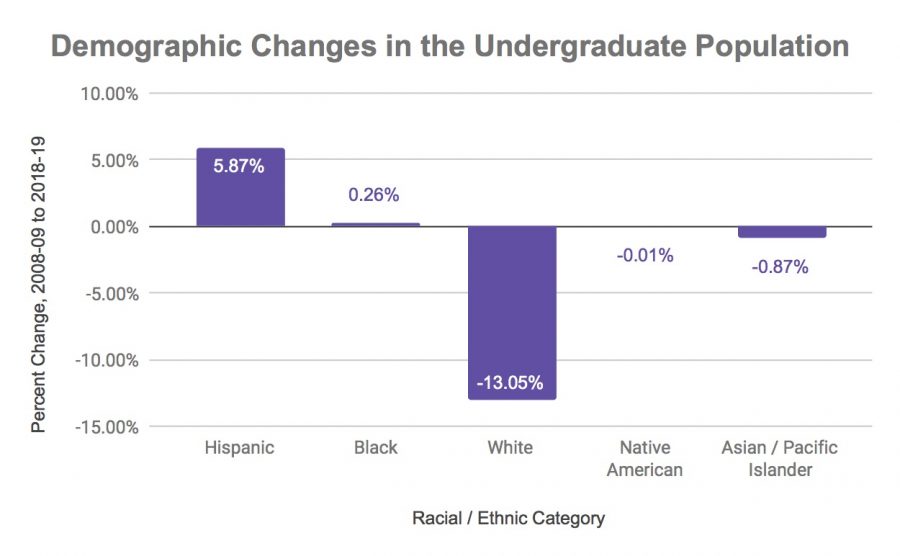

Provost Jonathan Holloway said Northwestern will be defined by how it adjusts to nationwide demographic changes among those attending elite colleges. In the next decade, he said, students will mostly be from the southern and western United States, decreasingly white and increasingly stratified between upper and lower classes, often to the detriment of the middle class.

Northwestern is already seeing the result of changing financial aid and demographic commitments — the average financial aid package is now $51,913 as opposed to $29,411 in 2008-09, according to the University’s Common Data Set. He said both students who can afford the price of admission and those with limited resources can attend the University if they are admitted, which for the latter is made possible through financial aid packages. Though middle-class applicants are admitted, the inability of the school to provide requisite financial aid makes them increasingly less likely to attend.

Holloway said the isolation of the middle class will be exacerbated in the future. The larger low-income population will force the University to meet new challenges, some of which they are already facing.

“(It’s) going to mean something different for the University in terms of services that are needed, especially a Southwestern population that doesn’t need winter coats (at home),” Holloway said. “There are more students who have basic needs to be a successful student. And the University has to catch up in terms of providing. That’s now. That’s a today problem. And if we aren’t being careful about that, that’ll be a humongous problem in five years, ten years.”

The incoming change is comparable to the effects of opening up elite college admissions to black students in the 1960s and women in the 1970s, Holloway said, though he noted Northwestern had allowed both groups long before. Diversifying universities created “radical” changes to culture, curricula and pedagogy.

While Northwestern’s black undergraduate population has only experienced a meager increase from 5.50 percent to 5.75 percent over the last ten years, increases in the Hispanic and multiracial populations have made NU a majority-minority school. White students now make up 44.82 percent of the undergraduate population, as opposed to 57.87 percent in 2008-09. Additionally, the University recently met its goal of having 20 percent of the incoming class be Pell-eligible by 2020.

Like in past eras, the demographic changes will require the Northwestern of tomorrow to be more sensitive to the needs of increasingly larger groups — which will not be easy, Holloway cautioned.

“With the demographic change coming, it’ll force new questions to be asked,” Holloway said. “It’ll force new practices to be put into place to make sure students can thrive, and it’s going to be bumpy.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @birenbomb