Pulitzer Prize-winning poet brings stories of African-American creatives to life

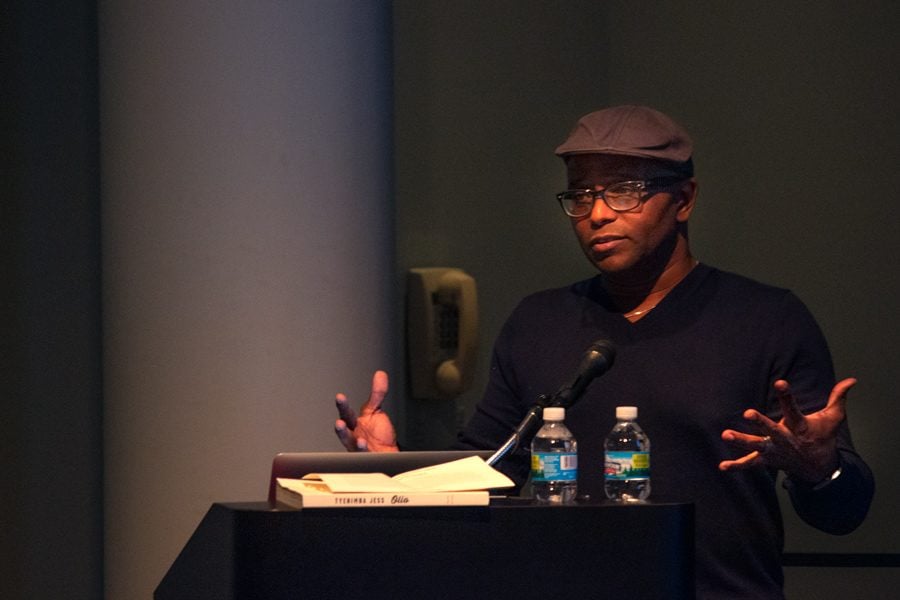

Evan Robinson-Johnson/The Daily Northwestern

Tyehimba Jess reads his poems. The poet said he likes to tell less-known stories from history.

February 1, 2019

Author Tyehimba Jess said while writing his Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry book “Olio,” he was inspired to tell the stories of people who have been left out of history.

Jess spoke at the Block Museum of Art on Thursday, reading excerpts from his poetry book “Olio” as part of the newly-launched Litowitz MFA+MA Creative Writing Speaker Series. Jess’s work furthers the museum’s commitment to telling stories from many perspectives, said Susy Bielak, the museum’s associate director of engagement and curator of public practice.

Jess said he is “fascinated” with stories of African-American creatives in the 19th and 20th centuries, which is why he incorporated them into “Olio.” The writer shares stories from people such as Millie and Christine McCoy, conjoined twins who were born into slavery in the South during the 19th century. The twins eventually earned enough money through their traveling act to buy the plantation on which they used to work.

“When I read them I was like, ‘How come I didn’t know all this?’ and that’s part of the energy that I came to these stories with,” he said. “I felt like people should know.”

The title of Jess’s poetry book, “Olio,” is a word used to describe the middle section of a minstrel show –– a 19th-century form of entertainment in which white actors performed racist caricatures of black people. Jess described the practice as “an insidious form of psychological warfare disguised as entertainment.” The poems Jess shared during the event centered around the idea of a minstrel.

Jess also shared a poem about Bert Williams and George Walker, two minstrel comedians who Jess describes as “the 19th- or early 20th-century version of Key and Peele.” Williams and Walker challenged the prevailing norms of minstrel acts by portraying three-dimensional characters of black people, rather than the caricatures traditionally displayed, Jess said.

Although these minstrel shows are a thing of the past, Jess said “we see vestiges of the minstrel show today.”

One audience member, Mike Puican, has known Jess for several years through the Chicago poetry scene. A poet himself, Puican said he respects Jess’s energetic style, professionalism and work ethic. Jess’s performative readings bring the story to life, he added.

First-year English graduate student Natalie Rose Richardson, who attended the event, said she was interested in the historical approach Jess takes in his writings.

“He has this way with words, both in writing and in person, that makes you feel like he’s just on the cutting edge of something,” Richardson said. “He’s also a warm and approachable speaker, which can be refreshing in the academic setting.”

Jess said he likes to tell less-known stories from history. His book took him about seven years to write, but he was constantly motivated by his curiosity to learn more, he said.

“It’s about talking back to history,” Jess said. “I’m trying to give voice to people who were left out of our histories.”

Email: savannahkelley2021@u.northwestern.edu

Twitter: @kelleysasa