District 65 pledges to ‘stay the course’ after DeVos revokes guidelines protecting students of color from suspensions

Daily file photo by Daniel Tian

Washington Elementary, 914 Ashland Ave., is an elementary school in District 65. Superintendent Paul Goren confirmed his commitment to disciplinary protections for students of color after a recent decision from the Department of Education.

January 11, 2019

In response to Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’ rescinding of Obama-era regulations designed to protect students of color from over-suspension, Evanston/Skokie School District 65 doubled down on its commitment to fair implementation and reflection on its disciplinary practices.

“The direction we’re heading in is to be a restorative school community that really pays attention to the experience that kids have in our schools and not a punitive community,” District 65 Superintendent Paul Goren said. “The recent decision pushes school districts around the country to be punitive rather than restorative.”

DeVos announced her decision to revoke the 2014 guidelines in a joint statement with the U.S. Justice Department in December. The regulations suggested schools could run into civil rights violations if they disciplined students of color at a higher rate, even if the policies did not intend to discriminate.

DeVos cited surveys of teachers “confirming the guidance’s chilling effect” on teachers and administrators, suggesting the Obama administration had gone too far in protecting students of color.

“I’ve heard from teachers and advocates that the previous administration’s discipline guidance often led to school environments where discipline decisions were based on a student’s race and where statistics became more important than the safety of students and teachers,” DeVos said in a statement. “Our decision to rescind that guidance today makes it clear that discipline is a matter on which classroom teachers and local school leaders deserve and need autonomy.”

Ald. Cicely Fleming (9th), who serves on the board of the Organization for Positive Action and Leadership — a grassroots organization focused on equity in Evanston — emphasized that she supports discipline when it is necessary, but said the district needs to make clear standards and reporting procedures.

“We have disciplinary reports to show that they’re totally out of whack when you look at who’s disciplined and who’s suspended compared to the percentages of students in school,” Fleming said. “We’re not calling for a total absolution of discipline, but we’re calling for discipline to be applied fairly across race and gender in our schools.”

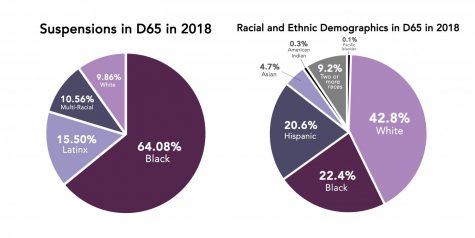

The first graph represents the number of suspensions in District 65 in 2018 disaggregated by race. Data was not available for the number of suspensions of Asian and Native American students in 2018. The second graph shows the racial and ethnic breakdown of students in District 65 in 2018. Source: District 65 and Illinois Report Card.

‘Stay the course’

Goren said the district has focused on suspensions since before the Obama administration guidelines in 2014 and suggested the decision would not impact Evanston students directly.

“Our stance is that we’re going to stay the course,” Goren said. “We truly believe that one way to address issues of achievement and opportunity gaps … is to keep kids in school … which means a redefinition of how we think about suspension.”

In Sept. 2014 before the federal guidance, the school board created requirements for the superintendent’s office to approve all suspensions longer than five days. He said the school currently uses the Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports, a system to track discipline in school and guide teachers to implement rules fairly.

In addition, the district hired a director of black student success and a director for equity and community engagement in Jan. 2018; all educators are required to participate in racial equity training; and culture and climate teams at schools look closely at data disaggregated by race to hold the district accountable.

Goren described other alternatives to suspension, including restorative justice, reflection and a meeting with parents, teachers and the student. He said these methods can make discipline a “learning opportunity.”

Fleming also added that Illinois passed state requirements two years ago requiring additional reporting for suspension.

“My hope would be that districts nationwide, and in particular Evanston, have already made this commitment in their district,” Fleming said. “But when you look at communities that may be leaning more to the right than Evanston does, you might see these discipline numbers going up again because they go back to their old ways of doing things that are not regulated under the law anymore.”

Shut out

Though District 65 has taken steps to improve outcomes for students of color, both Fleming and Goren recognized there is room for improvement.

In 2018, 64.08 percent of suspensions were black students, though they make up only 22.4 percent of the district.

“We can no longer just sit back and say, ‘Hey, the school’s doing really well,’ because we can look at data disaggregated by race and disaggregated by gender and we can actually make decisions on how we can intervene, what supports we can have, how we can use our resources,” Goren said.

Fleming said the district also needs to do a better job of transparency for punitive measures other than suspensions where students are missing class time to go to the principal’s office or talk to teachers in the hall. She described going to schools and seeing two or three black students sitting outside the main office, not in class and not learning.

Fleming said minor disciplinary measures should be recorded under PBIS, but when OPAL filed a Freedom of Information Act request to receive the numbers, they did not receive sufficient information.

Fleming said black communities are underserved and over-disciplined in schools — and then overpoliced and incarcerated at home. This is the essence of the school-to-prison pipeline, which both Fleming and Goren discussed.

“We are conditioning people to think ‘I don’t belong in the social structure,’” Fleming said. “If our society is set up on this track of do well in school, get a good job, be successful, and our first stop is do well in school, and our students are not doing well in school by either being underserved or over-disciplined … we’re not even getting to step one.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @caity_henderson