Psychology and biology majors among highest level of underemployment, study shows

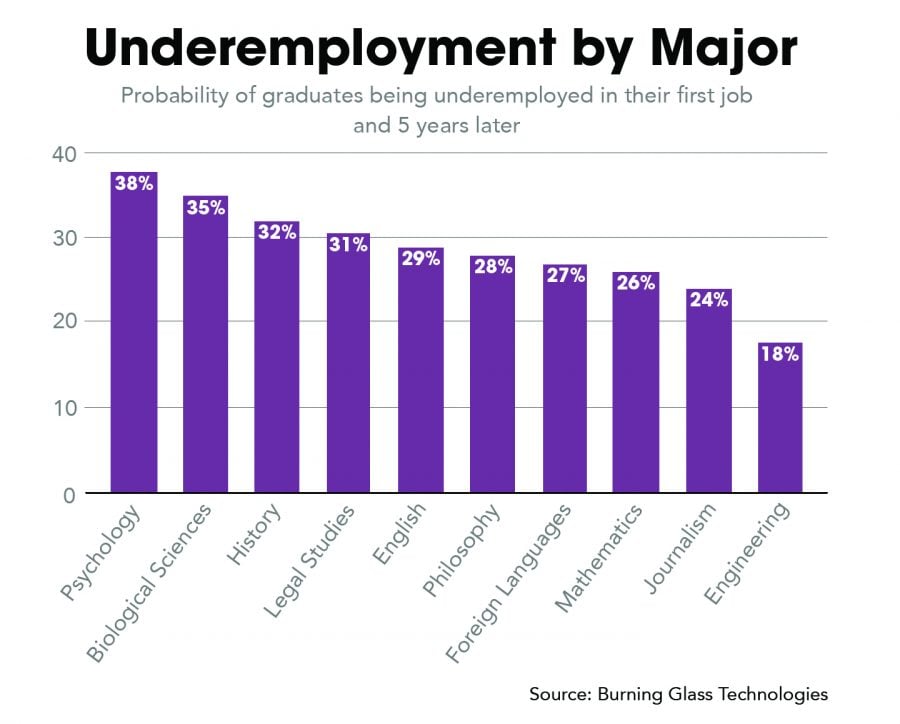

Probability of graduates being underemployed, broken down by major. Psychology and Biology majors are two of the most underemployed groups.

November 20, 2018

Forty-three percent of college graduates are underemployed in their first job, according to a recent study by Burning Glass Technologies, a job analytics firm. Two-thirds of these students remain underemployed for five years.

At Northwestern, 73 percent of undergraduates are employed after graduation, while 21 percent seek post-undergraduate education and 3 percent are still actively seeking jobs, according to a survey for the four graduating classes before 2018 conducted by Northwestern Career Advancement. Data on underemployment is unavailable.

Mark Presnell, executive director of NCA, said it’s difficult to collect this data because it “has never really been defined in our field.”

“Nobody has really adopted what underemployment means,” he said. “That doesn’t help us as an institution to clarify, but our students do really well after graduation.”

Underemployment is when college graduates work in jobs that are below their level of education. The study showed majors with the highest rates of underemployment include psychology and biological sciences, at 38 percent and 35 percent respectively.

Several faculty members in the psychology and biology departments at Northwestern said since many of their graduates go to graduate school rather than look for bachelor’s level positions, the study’s calculation of underemployment for these students may be skewed.

According to the NCA’s survey, 64 percent of psychology graduates are employed, 27 percent sought post-undergraduate education and 4 percent are still actively seeking jobs. For biology graduates, 49 percent were employed, 42 percent sought post-undergraduate education and 1 percent are still actively seeking jobs.

Benjamin Gorvine, assistant chair and lead adviser of the psychology department, said psychology graduates often work in positions that are seen as intermediate jobs taken with the intent of later going to graduate school.

Gorvine calls these bachelor’s level positions “quasi-clinical.”

“I think there’s a risk that some of those might’ve been grouped in with this underemployment category,” he said.

The study outlines three strategies for students to avoid underemployment: evaluating the risk of underemployment when selecting a major, building skills needed in future jobs and accruing meaningful work experiences before graduation.

The degree with the lowest level of underemployment, according to the study, is engineering with a rate of 18 percent.

Helen Oloroso, assistant dean and director of McCormick’s Office of Career Development, said clear career paths for engineering graduates may contribute to this, as well as diversity in skills.

“We’re looking for students, and are more likely to admit students, who have interests that go beyond engineering, math and science,” she said. “We bring in people who are already inclined that way and then our curriculum is designed to further develop that.

Kaitland Postley (Weinberg ’17), who graduated with a major in biology and a minor in U.S. History, said she had a difficult time securing a job after graduation.

Postley added that she wishes the biology department had given her greater guidance on how to apply her major to places other than medical school or a doctoral degree.

The study calculates the “Underemployment Risk Factor” for each major — which comes from the probability of underemployment, the cost of underemployment and the occupational concentration of graduates for each field of study — and urges students and families to take this into account when planning for college.

While students and faculty said they believe the risk of underemployment should be considered by undergraduates, many also worry that relying too heavily on this metric may hinder students from pursuing areas of study they are truly passionate about.

“I understand what they’re trying to do and they’re looking at this from a pragmatic economic perspective,” Gorvine said. “But I think it undervalues and underestimates the ways in which liberal arts degrees across a range of fields prepare you for the workforce.”

Sean Ages (Weinberg ’09) graduated with a degree in economics with the hope it would lead to greater job prospects, despite not finding the subject engaging. However, Ages said the only jobs he was offered after graduation did not utilize his degree.

Ages said he has mixed feelings about the usefulness of the risk factor metric.

“Part of me still thinks that universities are not supposed to be purely vocational,” he said. “And the practical side of me thinks that students ought to major in something that has at least a modicum of real-world applicability.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @gracelougheed