Northwestern alumnus inspires federal law aimed at protecting whistleblowers

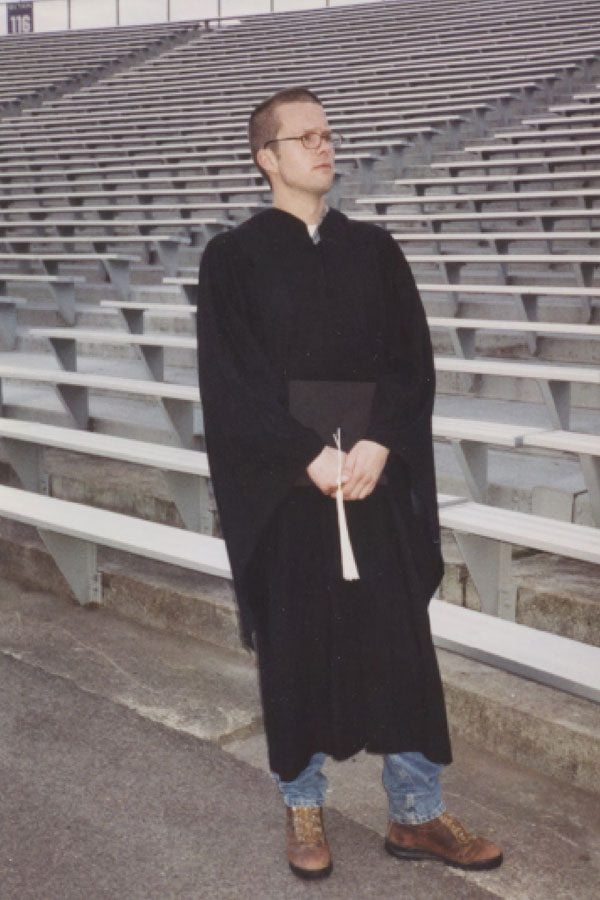

Chris Kirkpatrick poses at his graduation from NU in 1999, where he earned a degree in clinical psychology. The U.S Senate passed a bill in his name last month, after he was ousted from his job at a Veterans Affairs hospital in 2009 for whistleblowing and died by suicide.

November 20, 2017

During a regular day of work at a Veterans Affairs hospital, Chris Kirkpatrick (SPS ’99) bragged of his dog training abilities. But when he issued a command, his dog would not obey.

This was just one illustration of the humor Kirkpatrick brought to the workplace, said Lin Ellinghuysen, his union representative.

“He could take a joke,” she said. “He was very light-hearted. But he took his career, what he was doing, very seriously.”

Kirkpatrick took his own life after he was ousted from his position in 2009 at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ Tomah Medical Center in Wisconsin, according to a police report. Before leaving, he had raised concerns about the overmedication of opiates, namely that it made patients inattentive and therefore untreatable during therapy sessions.

Last month, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed the Dr. Christopher Kirkpatrick Whistleblower Protection Act of 2017 to provide more safety for whistleblowers in government agencies. The act, introduced by U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), seeks to send a “strong message that federal whistleblowers like Chris deserve protection.”

“Chris Kirkpatrick did the right and honorable thing when he raised concerns about the over-prescription of opioids to veterans,” Johnson said in a October news release. “Today we are sending a strong message that … attempts to intimidate or silence whistleblowers are unlawful.”

At Northwestern, Kirkpatrick earned a degree in clinical psychology to pursue his long-desired goal of counseling veterans and working toward a license to practice. It was a “natural progression,” his sister Katy Kirkpatrick said, because he loved people and wanted to serve others.

“To finally reach a goal that you’ve been working toward for quite some, (he was) very elated,” she said. “We were all very, very proud of him.”

Chris Kirkpatrick also loved animals growing up and was a natural caretaker, his sister said, noting his deep affection for his dog, Kali.

At the Tomah Center, patients affectionately referred to Chris Kirkpatrick as “Dr. K,” Katy Kirkpatrick said. Even during his termination hearing, supervisors praised his clinical professional skills, according to Ellinghuysen’s notes from the hearing.

The reasons for his termination were insubstantial, Ellinghuysen said. The termination notice cited timekeeping errors, due in part to a violation of labor laws he was instructed to commit by supervisors, according to the notes.

In addition to overmedication, Chris Kirkpatrick raised concerns about a patient who threatened to hurt him and his dog, according to Ellinghuysen’s notes. During the 2009 termination hearing, Kirkpatrick said his criticism of managers’ decision not to discharge the patient led to his termination.

One of Kirkpatrick’s last wishes was a support system to help clinical psychologists overcome the kind of stress and emotional trauma he had experienced, according to the notes.

“Lin, will you try to do something for me? … Try to get a support system so that no one else has to go through what I did,” Kirkpatrick asked Ellinghuysen after the hearing, according to her notes. “Will you please do that?”

Kirkpatrick was found dead several hours later, the police report said.

Ellinghuysen said she believes the termination decision also stemmed from her client’s decision to speak openly about opioid medication.

Kirkpatrick was one of many VA employees who faced retaliation for raising concerns about prescription practices, mishandling of funds and other instances of negligence. In 2015, his story gained national attention when whistleblower Ryan Honl spoke publicly about similar concerns.

Testimony to Congress from Honl and Sean Kirkpatrick, Chris Kirkpatrick’s brother, sparked separate investigations by the VA and the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. The investigations found that physicians at the Tomah Center — nicknamed “Candy Land” by patients — had engaged in excessive prescription of opioids.

The investigations also found that VA supervisors were rarely held responsible for retaliating against whistleblowers and cultivated a “culture of fear.” The new law requires heads of government agencies to prohibit retaliation and inform potential whistleblowers about available protections.

Additional provisions aim to prevent “prohibited personnel action” by supervisors, requiring agency heads to propose suspension of at least three days for the first infraction and “removing the supervisor” for the second. The law does not make clear whether the suspension would be paid or what constitutes a removal.

Despite efforts by lawmakers, critics say the law might not do enough to protect whistleblowers.

Agency heads make the last call on proposed punishments for supervisors, which could cause conflict if it was the agency head who proposed the punishment in the first place.

Richard Tremaine, a VA employee and whistleblower, said though he hopes the bill will make a difference, the VA needs to embrace internal change.

“The bill is not going to be the impetus for change,” he said. “It has to be the leadership of the VA that follows through on their promise to embrace whistleblowers. … You won’t find a single whistleblower (in the VA) that has come forward that doesn’t love veterans.”

Nevertheless, Katy Kirkpatrick said the law honors her brother’s name.

“It will not only help the VA employees, but all federal employees,” she said. “It honors his legacy, and more importantly his work. … He was just a tremendous individual.”

This story was updated Nov. 23 to clarify that Richard Tremaine is a whistleblower.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @_perezalan_